What Happens When Your Heart Valves Don’t Work Right

Your heart has four valves-aortic, mitral, tricuspid, and pulmonary-each acting like a one-way door. They open to let blood flow forward and snap shut to stop it from leaking back. When these valves get stiff, narrow, or leaky, your heart has to work harder. Over time, that strain can lead to heart failure, irregular heartbeats, or even sudden death.

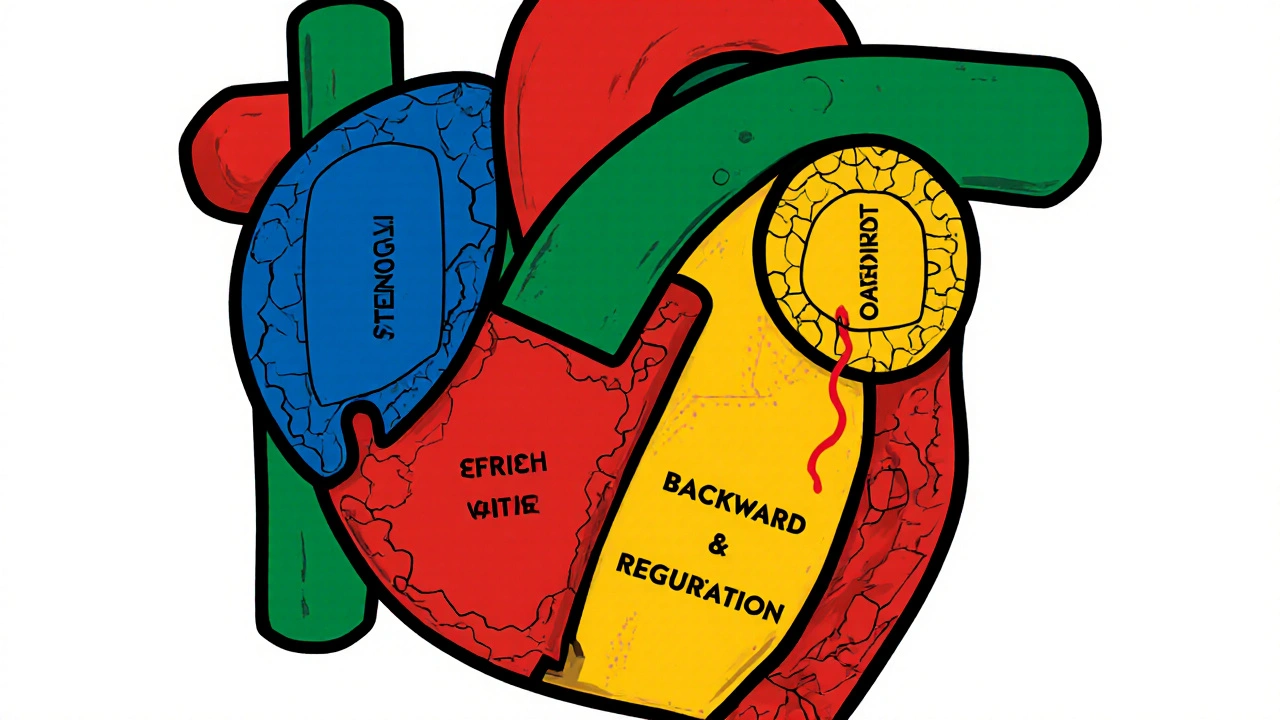

Two main problems cause most valve diseases: stenosis and regurgitation. Stenosis means the valve opening is too small-like a door that won’t fully open. Regurgitation means the valve doesn’t close properly-like a door that’s always slightly ajar, letting blood slip backward.

Stenosis: When Valves Get Stuck Shut

Aortic stenosis is the most common serious valve problem in older adults. About 2% of people over 65 have it. The valve leaflets thicken and calcify, turning flexible tissue into rock-like deposits. This forces the left ventricle to pump harder just to push blood through the narrowed opening. Severe aortic stenosis is defined by a valve area smaller than 1.0 cm², a pressure gradient over 40 mmHg, or a blood jet speed faster than 4.0 m/s.

Mitral stenosis is rarer in high-income countries but still common worldwide due to rheumatic fever. It narrows the space between the left atrium and ventricle, causing blood to back up into the lungs. People with this condition often wake up gasping for air at night (orthopnea) or feel winded even walking short distances.

Causes vary. In people over 70, 70% of aortic stenosis cases come from natural aging and calcium buildup. In younger patients under 70, about half have a bicuspid aortic valve-a birth defect where the valve has two leaflets instead of three. Rheumatic fever, now rare in Australia and the U.S., still causes 80% of mitral stenosis cases in developing nations.

Regurgitation: When Valves Leak

Regurgitation is the opposite problem: the valve doesn’t seal, so blood flows backward. In aortic regurgitation, oxygen-rich blood leaks from the aorta back into the left ventricle with every heartbeat. The heart compensates by expanding, but over time, it weakens. Symptoms include shortness of breath during activity, heart palpitations, and fatigue.

Mitral regurgitation is even more common. It can be primary (damage to the valve itself, like a torn chord) or functional (the valve is fine, but the heart chamber is enlarged and can’t close it properly). The latter often follows heart attacks or long-term high blood pressure.

Studies show that untreated severe mitral regurgitation cuts life expectancy by half. But here’s the catch: many people don’t feel symptoms until the damage is advanced. That’s why routine check-ups matter. A doctor listening for a murmur with a stethoscope can spot it early-something René Laennec figured out in 1819 when he invented the stethoscope.

How Symptoms Differ Between Stenosis and Regurgitation

Even though both conditions strain the heart, they feel different.

- Aortic stenosis patients often report chest pain (angina), dizziness, or fainting during activity. About half have heart failure symptoms like swollen ankles or trouble breathing.

- Aortic regurgitation usually shows up as fatigue and a racing heartbeat, especially when lying down.

- Mitral stenosis causes lung congestion-coughing at night, needing extra pillows to sleep.

- Mitral regurgitation leads to general tiredness. People say they can’t keep up with their kids, or they’re always winded climbing stairs.

One study found that 79% of mitral regurgitation patients described constant fatigue before treatment. Another found 87% of severe aortic stenosis patients couldn’t do basic chores like carrying groceries or cleaning the house.

Surgical Options: From Open-Heart to Tiny Catheters

When valve disease gets bad enough, surgery is the only fix. But today’s options are nothing like the open-chest procedures of the 1980s.

Surgical valve replacement is still the gold standard for many. The surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical one (lasts forever but needs lifelong blood thinners) or a tissue valve (from pig or cow tissue-doesn’t need blood thinners but wears out in 15-20 years).

Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacement (TAVR) changed everything. Instead of cracking open the chest, a catheter is threaded through the groin artery to push a new valve into place. It’s now the first choice for patients over 75 or those with high surgical risk. The PARTNER 3 trial showed TAVR patients had 12.6% lower death rates at five years compared to open surgery.

For mitral regurgitation, MitraClip is a game-changer. A tiny device is guided through a vein to grab the leaking leaflets and clip them together. The COAPT trial showed it cut death rates by 32% compared to meds alone in patients with functional regurgitation.

Even tricuspid valve repair is now possible with the FDA-approved Evoque system (approved March 2023). And new devices like Cardioband and Harpoon are in trials, aiming to fix leaks without open surgery.

Who Gets Treatment and When

Timing is everything. Waiting too long can be deadly. For aortic stenosis, survival drops to 50% within two years after symptoms appear-unless you get a valve replaced. Experts now recommend surgery even before symptoms hit if the valve is severely narrowed and the heart is starting to weaken.

For regurgitation, the rule is different. If the heart is still strong and the leak is mild, watchful waiting is fine. But if the left ventricle starts enlarging or pumping weakly, surgery should happen before symptoms show up. One cardiologist put it bluntly: “Waiting for fatigue to hit is like waiting for the smoke alarm to go off before you put out the fire.”

Not everyone needs surgery. Mild stenosis or regurgitation can be managed with meds, regular echocardiograms, and lifestyle changes. But if your valve is severely damaged, meds won’t fix it-they just buy time.

What Recovery Really Looks Like

Recovery isn’t the same for everyone.

TAVR patients often go home in 2-3 days. Many report feeling better within weeks. One patient on a heart forum wrote: “I went from struggling to walk to the mailbox to hiking 3 miles in two months.”

Open-heart surgery? That’s harder. Sternotomy (cutting through the breastbone) takes months to heal. People describe constant pain, trouble lifting anything heavy, and needing help with simple tasks for 6-8 weeks. “I couldn’t hug my grandchildren,” one man shared. “It took two months before I could lift them.”

After mechanical valve replacement, you’ll need blood thinners like warfarin for life. You’ll need regular INR checks-twice a week at first, then monthly. Target levels are 2.5-3.5 for mitral valves, 2.0-3.0 for aortic ones.

Bioprosthetic valves don’t need lifelong anticoagulation, but they wear out. About 21% show signs of deterioration by 15 years. Newer tissue treatments may extend that to 25+ years.

The Future Is Minimally Invasive

By 2030, experts predict 80% of valve procedures will be done through catheters, not open surgery. The reason? Better devices, faster recovery, and an aging population. In the U.S., 65% of aortic valve replacements in patients over 75 are now TAVR-up from just 12% in 2011.

But access isn’t equal. High-income countries perform 18 valve procedures per 100,000 people each year. Low-income nations? Just 0.2 per 100,000. Many people in rural areas or developing countries still die from valve disease because they can’t get care.

Meanwhile, research is pushing boundaries. Next-gen bioprosthetic valves made with engineered tissues could last decades. AI is being used to predict when a valve will fail before symptoms appear. And clinical trials are testing whether TAVR is safe for patients as young as 60.

Don’t Ignore the Warning Signs

Valve disease doesn’t always scream for attention. It whispers. Fatigue. Shortness of breath. Feeling winded climbing stairs. A racing heartbeat after light activity. These aren’t just “getting older.” They could be your heart struggling.

One survey found 28% of patients felt dismissed by doctors until their symptoms became severe. Don’t let that be you. If you’re over 65, or have a history of rheumatic fever, heart attack, or a family history of valve disease, ask your doctor for a simple echocardiogram. It’s painless, takes 20 minutes, and can save your life.

What to Ask Your Doctor

- Is my valve problem stenosis or regurgitation?

- How severe is it? What are the numbers from my echo?

- Is my heart starting to enlarge or weaken?

- Should I be monitored every 6 months or wait longer?

- Am I a candidate for TAVR or MitraClip, or do I need open surgery?

- What are the risks of waiting versus having surgery now?

Can heart valve disease be cured without surgery?

No-once a valve is severely damaged by stenosis or regurgitation, medication can only manage symptoms. It can’t fix the physical damage. Surgery or a catheter-based procedure is the only way to restore normal blood flow. Early detection helps avoid complications, but it doesn’t eliminate the need for intervention when the valve is failing.

How do I know if I need surgery now or can wait?

Your doctor will look at three things: how bad the valve damage is (measured by echo or CT scan), whether your heart is starting to weaken (ejection fraction and chamber size), and whether you have symptoms. For aortic stenosis, if your valve area is below 1.0 cm² and your heart is showing signs of strain-even without symptoms-surgery is usually recommended. For regurgitation, surgery is advised if the left ventricle is enlarging or pumping weakly, regardless of symptoms.

Is TAVR better than open-heart surgery?

For patients over 75 or those with other health issues that make open surgery risky, TAVR is safer and has faster recovery. For younger, healthier patients, open surgery with a mechanical valve may last longer and avoid repeat procedures. The choice depends on age, overall health, valve type, and life expectancy. There’s no one-size-fits-all answer.

What’s the difference between a mechanical and tissue valve?

Mechanical valves are made of metal and last a lifetime, but you must take blood thinners like warfarin every day to prevent clots. Tissue valves come from animal tissue (pig or cow) and don’t require lifelong blood thinners, but they wear out in 15-20 years and may need replacement. Younger patients often choose mechanical; older patients usually pick tissue.

Can I live a normal life after valve replacement?

Yes-most people return to normal activities within a few months. Many report better energy, less shortness of breath, and the ability to walk, garden, or play with grandchildren again. Recovery time varies: TAVR patients often feel better in weeks; open-heart patients may take 3-6 months to fully recover. Regular check-ups and following your doctor’s advice on activity and meds are key to long-term success.

Next Steps if You’re Concerned

If you’re over 65 and have unexplained fatigue, shortness of breath, or chest discomfort, talk to your doctor about an echocardiogram. It’s the only way to see your valves clearly. If you’ve had rheumatic fever in the past, get checked every few years-even if you feel fine. Valve disease doesn’t always hurt. But it always steals your life, one breath at a time.

Peter Aultman

November 13, 2025 AT 06:25Sean Hwang

November 13, 2025 AT 18:37Nathan Hsu

November 15, 2025 AT 17:24Ashley Durance

November 16, 2025 AT 06:33Eleanora Keene

November 16, 2025 AT 22:54Barry Sanders

November 18, 2025 AT 13:42Scott Saleska

November 19, 2025 AT 09:45Joe Goodrow

November 20, 2025 AT 02:09