When your liver is failing, your kidneys don’t just take a backseat-they can shut down completely, even if they’re structurally fine. This isn’t a coincidence. It’s hepatorenal syndrome, a deadly chain reaction where advanced liver disease triggers sudden, severe kidney failure without any physical damage to the kidneys themselves. It’s not common, but when it happens, it’s urgent. Up to 10% of hospitalized patients with liver failure develop it, and for those with end-stage cirrhosis, the risk jumps to 40%. Most people diagnosed are in their 50s. And without treatment, Type 1 hepatorenal syndrome can kill you in under two weeks.

What Exactly Is Hepatorenal Syndrome?

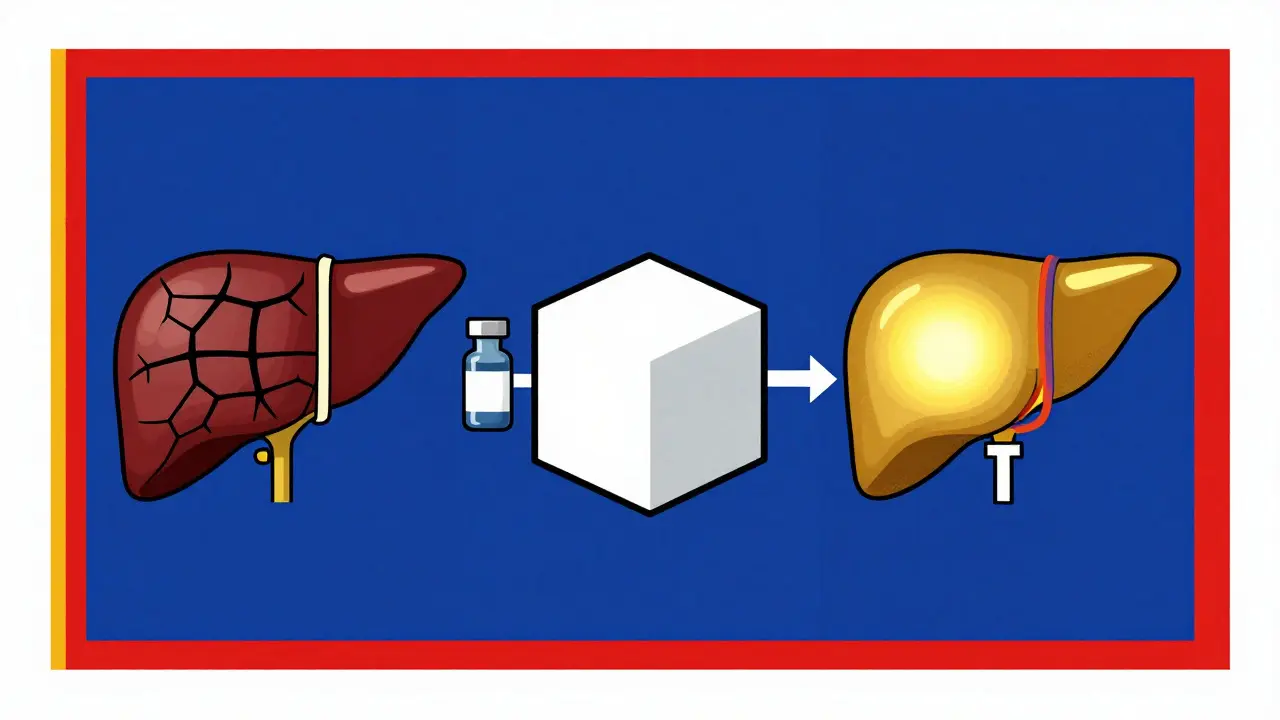

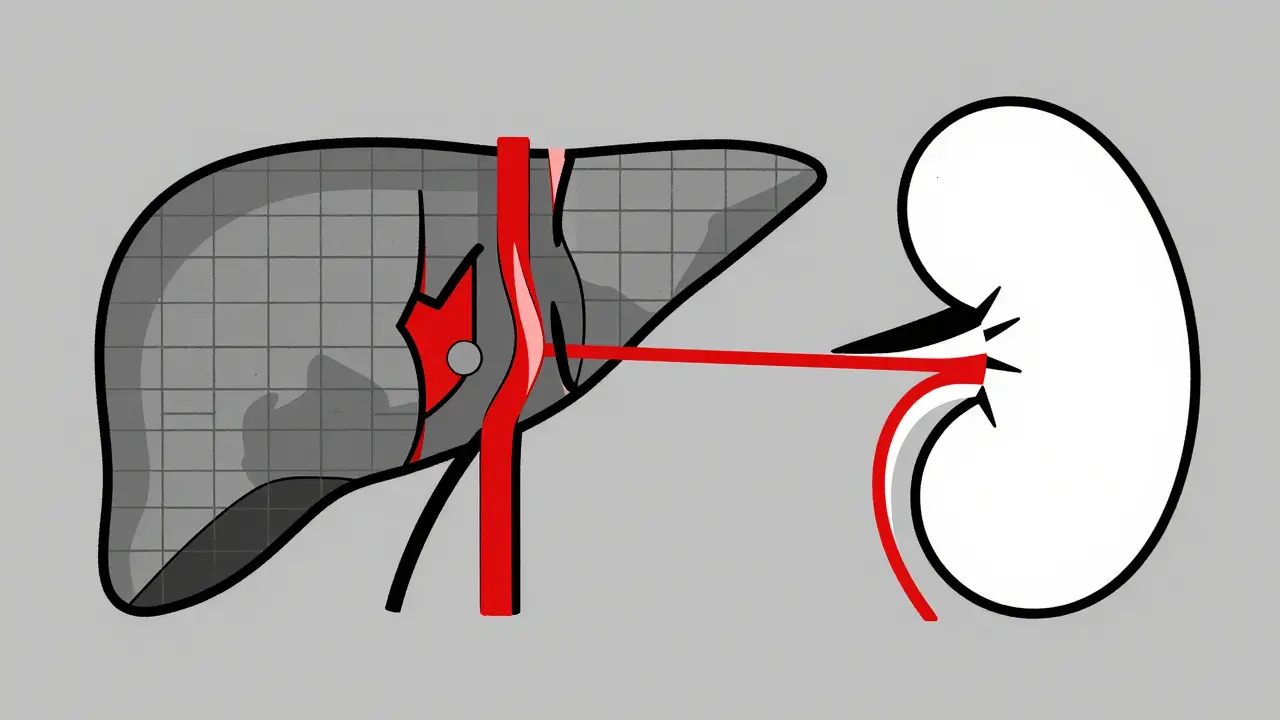

Hepatorenal syndrome (HRS) isn’t kidney disease. It’s liver disease turning on your kidneys. Your kidneys aren’t broken-they’re just starving for blood. In cirrhosis, scar tissue blocks blood flow through the liver. This raises pressure in the portal vein, which triggers massive dilation of blood vessels in the intestines. Your body thinks it’s losing blood, so it tightens arteries everywhere else, including in your kidneys. The result? Your kidneys get less blood, filter less waste, and creatinine builds up in your blood. But if you took a biopsy, you’d see normal kidney tissue. That’s the cruel trick of HRS: your organs are failing, but nothing’s visibly damaged.

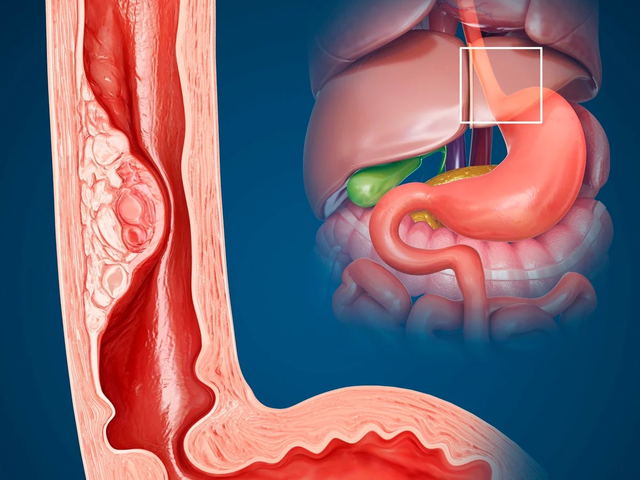

There are two types. Type 1 is the emergency. Creatinine spikes above 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. It’s fast, it’s brutal, and it’s often triggered by infections like spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), bleeding in the gut, or heavy alcohol use. Type 2 is slower. Creatinine stays between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL. It’s tied to stubborn ascites-fluid in the belly that won’t go away, no matter how many diuretics you take. Both types are diagnosed by ruling everything else out. No signs of infection, no kidney stones, no drugs like NSAIDs or antibiotics that could harm the kidneys. And crucially, creatinine doesn’t drop after stopping diuretics and giving albumin.

Why Do Doctors Miss It So Often?

One in three patients with HRS is misdiagnosed. Why? Because most doctors aren’t trained to think beyond the obvious. High creatinine? Must be acute kidney injury from dehydration or sepsis. But in cirrhosis, the rules change. You can have low blood pressure, fluid overload, and still have HRS. The key clues are hidden in the details: urine sodium under 10 mmol/L, urine osmolality higher than blood, almost no protein or blood in the urine. These aren’t standard tests in most ERs. A 2021 study showed only 58% of non-specialists could correctly identify HRS from case studies.

Even when suspected, delays are common. A 2022 patient survey found the average time to diagnosis was over seven days. That’s seven days where the kidneys keep worsening. Many patients are treated for heart failure or dehydration first. By the time HRS is confirmed, it’s often too late for the best treatments to work.

How Is It Treated? The Real Options

The only proven treatment for Type 1 HRS is a combo of terlipressin and albumin. Terlipressin is a vasoconstrictor-it tightens the over-dilated blood vessels in the gut, which tricks the body into restoring blood flow to the kidneys. Albumin helps hold fluid in the bloodstream, supporting circulation. Together, they work in about 44% of cases. But it’s not simple. Terlipressin can cause heart attacks, strokes, or limb ischemia. Dosing is tight: 1 mg every 4 to 6 hours, max 2 mg. Patients often report severe abdominal cramps. One patient on a liver forum said their dose had to be cut in half because of pain.

In the U.S., terlipressin wasn’t approved until December 2022. Before that, doctors used off-label combinations like midodrine (a blood pressure drug) and octreotide (a hormone blocker). These are less effective and harder to manage. Now, with FDA approval, the drug costs $1,100 per vial. A full 14-day course runs about $13,200. Insurance denials are common-even when patients meet all diagnostic criteria. Many can’t get it unless they’re at a transplant center.

For Type 2 HRS, the goal is managing ascites. TIPS (transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt) can help. It creates a tunnel inside the liver to reroute blood flow, reducing portal pressure. About 60-70% of patients see kidney function improve. But the trade-off? A 30% chance of developing hepatic encephalopathy-brain fog, confusion, even coma. It’s a gamble.

Transplant: The Only Real Cure

Nothing fixes HRS like a liver transplant. It’s the only treatment that addresses the root cause. Survival without transplant? For Type 1, just 18% survive a year with supportive care alone. With terlipressin and albumin? It jumps to 39%. But with a transplant? It’s 71%. That’s the difference between dying and living.

That’s why experts now say: if you have Type 1 HRS, get on the transplant list immediately. Don’t wait for creatinine to drop. Don’t wait to see if terlipressin works. The 2023 European Liver and Intestine Transplant Association guidelines say: list everyone with Type 1 HRS, no exceptions. Your MELD-Na score-the system that ranks transplant priority-now includes kidney function. A high creatinine pushes you higher on the list. That’s new. That’s life-saving.

What’s on the Horizon?

Researchers are hunting for early warning signs. Right now, HRS shows up only after kidney damage is already happening. But new biomarkers like urinary NGAL (neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin) might catch it before creatinine rises. The PROGRESS-HRS trial is testing if NGAL levels above 0.8 ng/mL can predict HRS in high-risk cirrhotics before it hits. If it works, doctors could start treatment days earlier.

Other drugs are in trials. One, PB1046, targets vasopressin receptors to improve blood flow. Another, the alfapump®, is a wearable device that drains ascites automatically-helping Type 2 patients avoid the constant fluid buildup that worsens HRS. But these are years away from widespread use.

Right now, access is the biggest barrier. In North America, 63% of HRS patients get vasoconstrictors. In sub-Saharan Africa, it’s 11%. In most low-income countries, patients get only fluids and diuretics. Survival rates there are close to zero. The drugs exist. The guidelines exist. But the system doesn’t always deliver.

What Should You Do If You or a Loved One Has Cirrhosis?

If you have cirrhosis and your creatinine is rising, don’t assume it’s just dehydration. Ask for a specialist evaluation. Demand tests for urine sodium, osmolality, and protein. Push for albumin if you’re hospitalized. If you’re on diuretics and your belly keeps swelling, that’s a red flag. Tell your doctor you’re worried about HRS. Bring the ICA diagnostic criteria with you if you have to.

If you’re told you need a transplant, don’t delay. Even if your creatinine hasn’t hit 2.5 yet, if you have refractory ascites or an infection, you’re at high risk. Get evaluated now. The clock starts ticking the moment your liver fails.

And if you’re on terlipressin? Watch for chest pain, leg pain, or sudden confusion. Report it immediately. It’s not just side effects-it’s a sign your body is under too much stress. Dosing needs to be personalized. What works for one person might kill another.

Hepatorenal syndrome doesn’t come with warning signs. It doesn’t announce itself. It sneaks in when you’re already fighting a losing battle with your liver. But knowledge is power. Know the signs. Know the tests. Know your options. Because in HRS, timing isn’t just important-it’s everything.

Is hepatorenal syndrome the same as kidney disease?

No. Hepatorenal syndrome is not kidney disease. The kidneys themselves aren’t damaged-they’re working fine structurally. The failure is functional. It’s caused by severe liver disease triggering blood flow changes that starve the kidneys of oxygen and nutrients. That’s why a kidney biopsy looks normal. It’s the liver’s failure that’s poisoning the kidneys’ blood supply.

Can hepatorenal syndrome be reversed without a transplant?

Yes, sometimes-but only temporarily. Type 1 HRS can improve with terlipressin and albumin, with about 44% of patients seeing creatinine drop below 1.5 mg/dL. Type 2 HRS can improve with TIPS or better ascites control. But unless the underlying liver disease is fixed, HRS almost always returns. That’s why transplant is the only long-term solution. Medical treatments buy time, but they don’t cure.

What triggers hepatorenal syndrome?

The most common trigger is spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), an infection in the abdominal fluid, which accounts for 35% of cases. Other triggers include gastrointestinal bleeding (22%), acute alcoholic hepatitis (11%), and overuse of diuretics or NSAIDs. Even large-volume paracentesis (draining belly fluid) without albumin replacement can trigger it. Infection is the biggest red flag-if you have cirrhosis and get sick, get checked for HRS immediately.

Why is terlipressin not widely available in the U.S.?

Terlipressin wasn’t FDA-approved until December 2022. Before that, it was only available through special access or compounding pharmacies. Even now, it’s expensive-about $13,200 for a 14-day course-and many insurers deny coverage unless you’re at a transplant center. It’s also not commonly stocked in community hospitals. Most patients only get it if they’re admitted to a major academic medical center with a hepatology team.

How do you know if someone has Type 1 or Type 2 HRS?

It’s based on how fast creatinine rises and how high it gets. Type 1 is rapid: creatinine doubles to over 2.5 mg/dL in under two weeks. Type 2 is slow: creatinine stays between 1.5 and 2.5 mg/dL and is linked to fluid buildup that doesn’t respond to diuretics. Type 1 is life-threatening and needs immediate treatment. Type 2 is chronic and often managed with TIPS or long-term albumin infusions. Both require the same diagnostic exclusion rules.

Can you prevent hepatorenal syndrome?

You can’t prevent it entirely, but you can reduce the risk. Avoid NSAIDs, alcohol, and unnecessary antibiotics. Treat infections like SBP immediately. Always get albumin after draining large amounts of belly fluid. Keep your MELD-Na score low by managing fluid and sodium. And if you have cirrhosis, get regular kidney function checks-even if you feel fine. Early detection saves lives.

Pavan Vora

January 6, 2026 AT 05:12Wow, this is so eye-opening... I never realized the kidneys could just... shut down like that, even if they're fine? Like, it's not the kidneys' fault? That's wild. I'm from India, and we see so many liver patients here, but no one talks about this. My uncle had cirrhosis, and they just kept giving him diuretics... I wish someone had told us about HRS earlier. It's like the body's betrayal.

Ashley S

January 7, 2026 AT 12:56So basically, if your liver dies, your kidneys get punished? That’s so unfair. And now they want us to pay $13k for a drug that might kill you too? I’m just saying, why isn’t this covered by insurance? This system is broken.

Gabrielle Panchev

January 8, 2026 AT 12:46Let’s be real-this whole narrative is oversimplified. Yes, terlipressin helps some, but what about the fact that 56% of patients don’t respond? And the article conveniently ignores that many of those who do respond still die within months because the liver keeps failing? Also, TIPS isn’t some miracle-it increases encephalopathy risk by 30%, which is basically trading one nightmare for another. And let’s not pretend that transplant access is equitable; in rural America, you’re lucky if you even get a referral. The real issue isn’t treatment-it’s systemic neglect of end-stage liver disease patients, especially those without wealth or connections. This article reads like a pharma brochure with a side of guilt-tripping.

Venkataramanan Viswanathan

January 10, 2026 AT 03:16As a medical professional in India, I can confirm that hepatorenal syndrome is grossly underdiagnosed here. Most hospitals lack the resources to test urine sodium or osmolality. We rely on clinical suspicion alone. The cost of albumin and terlipressin is prohibitive. Many families choose palliative care because they cannot afford even one vial. The guidelines exist, but infrastructure does not. This is not a medical failure-it is a social one.

Vinayak Naik

January 11, 2026 AT 16:45Bro, this is straight-up nightmare fuel. Liver’s like a broken pump, kidneys are just sitting there like ‘yo, why’s the water pressure dropping?’ and then-bam-no more filterin’. I’ve seen this with my cousin. They gave him furosemide like it was candy, and his belly swelled like a balloon. No one said ‘HRS’ until he was in ICU. By then, it was too late. The terlipressin thing? Sounds like a high-stakes poker game with your life. And yeah, transplant’s the only real win-but good luck getting on the list if you’re poor or uninsured. This ain’t science, it’s a rigged game.

Matt Beck

January 12, 2026 AT 16:18It’s funny… we treat organs like they’re separate entities, but the body’s a web, man. A spider’s web. Pull one thread-the liver-and the whole thing trembles. The kidneys aren’t failing… they’re just listening to the wrong signals. It’s like your phone’s battery dies because the charger’s broken, but you keep blaming the phone. We’re so obsessed with fixing parts that we forget the system. Transplant isn’t just a cure-it’s a reset button. But who gets to press it? That’s the real question. 🤔

Kelly Beck

January 14, 2026 AT 05:42This is such an important post-I’m so glad someone took the time to explain this clearly. I have a friend who just got diagnosed with Type 2 HRS, and honestly, I didn’t even know what it was until I read this. You’re right: if you have cirrhosis and your belly keeps swelling, it’s not ‘just fluid’-it’s a red flag. Please, everyone reading this: if you or someone you love has liver disease, ask about HRS. Don’t wait. Advocate. Push. You are your own best advocate. And if you’re on terlipressin? I’m sending you so much strength. You’re not alone 💪❤️

Beth Templeton

January 14, 2026 AT 16:14So you’re telling me the solution is to give people a $13k drug and hope they live long enough to get a transplant? Cool. Got it. Meanwhile, the rest of us are just supposed to ‘push for tests.’ Yeah, right. Like that’s gonna happen in a 10-minute ER visit. This isn’t medicine. It’s a luxury game.

Tiffany Adjei - Opong

January 15, 2026 AT 19:51Wait, so terlipressin is only available at transplant centers? And insurance denies it even when you meet criteria? So what’s the point of having a ‘proven treatment’ if 80% of patients can’t access it? This isn’t healthcare-it’s a lottery. And the worst part? The article makes it sound like we’re all just not trying hard enough. Newsflash: most people don’t have time, money, or a PhD to navigate this mess. You don’t get points for awareness if the system won’t let you act on it.