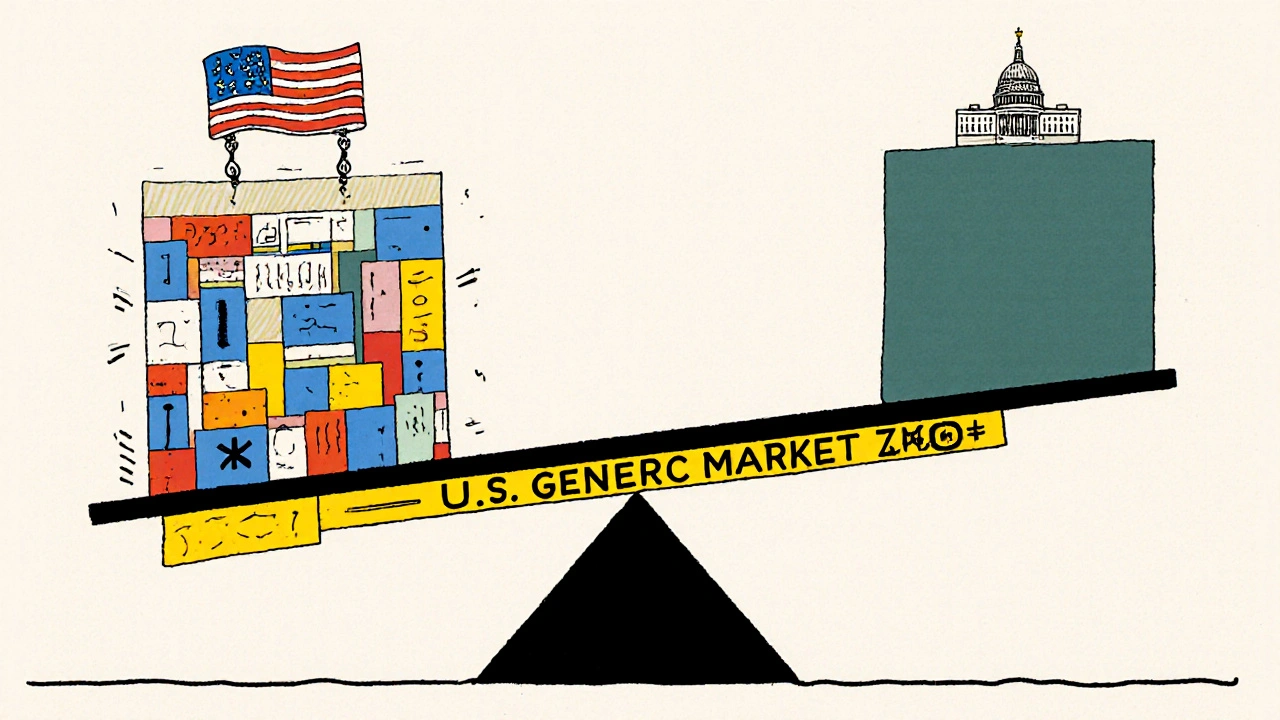

When you walk into a pharmacy in the U.S. and see a $6 copay for your generic blood pressure pill, it’s easy to think you’re getting a deal. But here’s the twist: generic drugs in the United States are often cheaper than in almost every other developed country - even though the U.S. pays more for brand-name drugs than anywhere else on Earth. This isn’t a contradiction. It’s the reality of how drug pricing works across the globe.

Why U.S. Generic Drugs Are Usually Cheaper

The U.S. market for generic medications operates differently than most other countries. About 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. are for generic drugs. That’s far higher than the global average of around 40%. Why? Because American insurers, Medicare, and pharmacy benefit managers push hard for generics. And once multiple manufacturers start making the same drug, prices drop fast. For example, when just two or three companies start producing a generic version of a brand-name drug, the price typically falls to 15-20% of what the original cost. With five or more competitors, it can plunge even lower. A 2019 FDA analysis found that after three generic manufacturers enter the market, prices drop by 70-80% from the original brand price. That’s why a 30-day supply of generic lisinopril (for high blood pressure) might cost you $4 at Walmart - while in Germany or France, the same pill could cost $8-$12. This isn’t because U.S. manufacturers are cheaper. It’s because competition is fierce. The FDA approves generics quickly, and U.S. buyers - from big insurers to Medicaid programs - buy in massive volumes. That gives them leverage. In countries like Japan or Canada, where governments set fixed prices or limit the number of generic makers, competition doesn’t get the same chance to drive prices down.Brand-Name Drugs Are Where the U.S. Pays the Most

Here’s where things flip. While generics are cheaper in the U.S., brand-name drugs cost 3-4 times more than in other rich countries. A 2022 RAND Corporation study found that U.S. list prices for brand-name drugs were 422% higher than in 33 other OECD nations. That means if a new cancer drug costs $5,000 in Switzerland, the same drug might cost $21,000 in the U.S. - before insurance. Why? The U.S. doesn’t negotiate drug prices the way most other countries do. In Canada, the UK, and France, government agencies set price caps. In Germany, they use value-based pricing. In the U.S., drugmakers set their own prices - and they set them high. Pharmaceutical companies argue they need those profits to fund research. And while that’s partly true, the U.S. is essentially subsidizing global innovation. When a new drug launches, the first buyers are often Americans. Later, other countries buy the same drug at lower prices because they don’t pay for R&D. The result? Americans pay more for the drugs that matter most - the ones that treat cancer, autoimmune diseases, and rare conditions. Meanwhile, the everyday pills - the ones most people take daily - are among the cheapest in the world.Net Prices vs. List Prices: The Hidden Math

You might hear conflicting reports. One study says U.S. drug prices are 2.78 times higher than other countries. Another says U.S. net prices are actually lower. How can both be right? It comes down to list price versus net price. List price is what’s on the sticker. Net price is what’s actually paid after rebates, discounts, and negotiations. In the U.S., drugmakers give huge rebates to insurers and pharmacy benefit managers - sometimes over 50% of the list price. That’s why Medicare Part D, which negotiates prices directly, often pays far less than the sticker price. A 2024 University of Chicago study found that when you look at net prices - what public programs actually pay - the U.S. spends 18% less on prescription drugs than Canada, Germany, the UK, France, and Japan. That’s because those countries don’t have the same rebate system. They set a single price, and that’s it. In the U.S., the system is messy, but it works: billions in rebates flow back into the system, lowering costs for public programs. But here’s the catch: those rebates don’t help uninsured patients. If you’re paying cash for a brand-name drug, you pay the full list price. And that’s where the pain hits hardest.

How Other Countries Keep Prices Low

Japan and France consistently have the lowest drug prices in the OECD. Why? They control supply. Japan limits how many manufacturers can produce a generic drug. France negotiates prices directly with companies and refuses to reimburse drugs they consider overpriced. In both countries, the government decides what’s worth paying for. In the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) uses a single buyer model. One entity - the NHS - buys all drugs. That gives them massive bargaining power. In Canada, provincial governments pool their buying power. Germany uses a reference pricing system: if a drug costs more than similar ones, it gets cut. The U.S. doesn’t have any of that. There’s no single buyer. No price cap. No refusal to pay. Instead, there’s a patchwork of private insurers, Medicare, Medicaid, and cash-paying patients - each with different rules.Medicare’s New Drug Negotiations: A Step Toward Change?

In 2022, the Inflation Reduction Act gave Medicare the power to negotiate prices for 10 high-cost brand-name drugs. The first round of negotiated prices came out in 2024. Here’s what they showed:- Medicare’s price for Jardiance (a diabetes drug) was $204 - while the average price in 11 other countries was $52.

- For Stelara (used for psoriasis), Medicare paid $4,490. Other countries paid $2,822 on average.

- In 9 out of 10 cases, the U.S. negotiated price was still higher than what other countries pay.

What This Means for You

If you’re taking a generic drug - statins, metformin, omeprazole, levothyroxine - you’re likely paying less than people in Australia, Germany, or Japan. That’s good news. But if you’re on a brand-name drug - especially for cancer, MS, or rheumatoid arthritis - you’re probably paying more than anyone else in the world. And if you’re uninsured or underinsured, that gap can be devastating. The key takeaway? Don’t assume high prices mean better quality. The U.S. doesn’t have the best drugs. It has the most expensive ones. And the system is built to protect brand-name profits, not patient wallets.What’s Next for Drug Pricing?

The next round of Medicare-negotiated drugs is due in early 2025. That could expand to 15-20 drugs, covering $100 billion in annual spending. If more countries start pushing back on U.S. pricing - like Australia did in 2024 by refusing to pay for a new Alzheimer’s drug priced at $50,000 per year - pressure will grow on U.S. manufacturers. Some experts, like Dr. Dana Goldman from USC, argue that the U.S. generic system works well and shouldn’t be broken. Others, like RAND’s Andrew Mulcahy, say the brand-name pricing model is unsustainable. The truth? Both are right. The U.S. has the best generic market in the world - and the worst brand-name market. The real question isn’t whether prices should be lower. It’s who should pay for innovation. If the U.S. keeps paying 4x more for new drugs, will other countries keep paying less? Or will they start pushing back harder - and force U.S. drugmakers to lower prices everywhere? For now, if you’re on a generic, keep taking it. You’re getting a global bargain. If you’re on a brand-name drug, ask your doctor about alternatives. Ask your pharmacy if a generic exists. And don’t assume high price equals high value. In drug pricing, the U.S. is the outlier - not the leader.Why are generic drugs cheaper in the U.S. than in other countries?

Generic drugs are cheaper in the U.S. because of intense competition. When multiple manufacturers produce the same drug, prices drop fast - often to 15-20% of the brand-name price. The U.S. approves generics quickly, and large buyers like Medicare and Medicaid buy in bulk, giving them negotiating power. Other countries limit the number of generic makers or set fixed prices, which slows price drops.

Are U.S. drug prices really the highest in the world?

For brand-name drugs, yes. The U.S. pays 3-4 times more than other rich countries. But for generics, the U.S. pays less - often 30% lower than countries like Germany, Canada, or France. The high overall U.S. spending comes from brand-name drugs, which make up just 10% of prescriptions but 90% of spending.

Does Medicare negotiate prices lower than other countries?

No. Even after negotiation, Medicare’s prices are usually higher than what other countries pay. For example, Medicare pays $204 for Jardiance, while the average price in 11 other countries is $52. Medicare can only negotiate down from U.S. list prices, not below international benchmarks. So while it saves money compared to U.S. list prices, it still pays more than most other nations.

Why do some generic drugs suddenly become very expensive?

Sometimes, all the generic manufacturers exit the market because prices get too low to make a profit. That leaves one company in control - a monopoly. That company can then raise prices dramatically. This happened with drugs like doxycycline and cyclophosphamide, where prices jumped 1,000% after competitors left. The FDA tracks this, but there’s no system to prevent it.

Can I buy cheaper drugs from other countries?

Technically, importing prescription drugs from Canada or other countries is illegal in the U.S. - though enforcement is rare. Some Americans buy medications through verified international pharmacies, especially for non-controlled substances. But there are risks: counterfeit drugs, shipping delays, and no U.S. regulatory oversight. It’s not recommended unless you’re working with a trusted, licensed international pharmacy.

Charmaine Barcelon

November 22, 2025 AT 03:37Why is everyone acting like this is some kind of revelation?? I’ve been buying lisinopril for $4 at Walmart for years-why are you all surprised??

Adrian Rios

November 22, 2025 AT 11:02Let’s be real-this whole system is a circus. The U.S. generic market works because we have thousands of manufacturers fighting over pennies, and the big insurers force them to slash prices just to stay in the game. But then, for the drugs that actually save lives-cancer meds, insulin, autoimmune treatments-we let pharma companies charge whatever they want because ‘innovation.’ It’s like we’ve built a car with a turbocharged engine for city driving but a rusted-out transmission for highways. We’re fine with cheap commutes until we need to go cross-country and get stranded. And guess who pays the most? The people who can’t afford to skip the highway.

Casper van Hoof

November 22, 2025 AT 19:23The dichotomy between generic and brand-name pricing reflects a deeper structural asymmetry in the U.S. healthcare economy. The market-based competition for commoditized pharmaceuticals produces efficient outcomes, whereas the lack of centralized price-setting mechanisms for high-value therapeutics results in rent-seeking behavior by pharmaceutical firms. This is not an anomaly; it is an institutional feature.

Richard Wöhrl

November 23, 2025 AT 08:51Important note: the price spikes in generics? They happen when manufacturers quit because the profit margin is too thin-sometimes under $0.01 per pill. And then, one company buys up the patents or just waits for everyone else to leave. Suddenly, they’re the only game in town. Doxycycline went from $20 to $1,800 for a 30-day supply. That’s not capitalism-that’s exploitation. The FDA knows this happens, but they don’t have the power to force new entrants. We need a public backup manufacturer for critical generics. Like, literally, a government-run pill factory for life-saving drugs. Not because we’re socialists-because we’re not idiots.

Pramod Kumar

November 24, 2025 AT 04:42Man, this is wild. In India, we pay maybe $0.50 for a month’s supply of metformin-same pill, same factory sometimes. But here in the U.S., even generics feel like a luxury? And then you hear about some new cancer drug costing $100K? I don’t know whether to laugh or cry. The system is broken, but not because people are greedy-it’s because the rules are written by lawyers and lobbyists, not doctors or patients.

Brandy Walley

November 25, 2025 AT 06:18lol so we’re supposed to be grateful for cheap pills while the rich get richer? yeah right. you think walmart’s $4 lisinopril is a gift? nah, it’s just the scraps they don’t care enough to overcharge for. Meanwhile, my friend’s insulin is $500 a month and she’s got insurance. this whole thing is a scam. stop pretending this is fair.

shreyas yashas

November 26, 2025 AT 10:00My uncle in Kerala gets his blood pressure meds for like 12 rupees a month. Same formula, same quality. I asked him why he doesn’t just order from the U.S. He laughed and said, ‘Beta, here we don’t pay for marketing. We pay for medicine.’ That stuck with me. The U.S. isn’t paying for drugs-it’s paying for ads, executives, and shareholder dividends.

Suresh Ramaiyan

November 27, 2025 AT 16:58It’s funny how we treat medicine like a commodity when it’s the one thing that can literally keep you alive. We’ve created a system where the cheapest drugs are the ones you take every day-because they’re boring and mass-produced. But the ones that could save you from death? Those are treated like rare art. We reward innovation, sure-but we punish access. Maybe the real question isn’t ‘why are prices so high?’ but ‘why do we let profit decide who lives?’

Katy Bell

November 28, 2025 AT 11:12Okay but… can we just appreciate how wild it is that I can get 90 days of levothyroxine for $10 at Costco? Like, I used to live in Canada and paid $40 for the same thing. And now I’m sitting here thinking-am I the only one who feels guilty about this? Like, I’m basically getting a global subsidy. Should I feel bad? Or should I just be glad I’m not paying $200?

Ragini Sharma

November 28, 2025 AT 22:47so u.s. generics = cheap. brand names = ripoff. but medicare still pays more than other countries?? lmao. so we’re the only country that can’t even negotiate well? someone get these people a tutor. also, why is no one talking about how pharma companies just tweak a pill and call it ‘new’? that’s not innovation, that’s a loophole. #pharmabullshit