Every year, thousands of patients in hospitals and clinics across the U.S. and Australia are harmed because someone misheard a medication order. Not because the doctor was careless, but because the system let them down. Verbal prescriptions - those quick, spoken orders given during emergencies, surgeries, or shift changes - are still part of daily care. But they’re also one of the most dangerous steps in the entire process. The good news? We know exactly how to make them safer. And it’s not about eliminating them. It’s about doing them right.

Why Verbal Prescriptions Still Exist

You might think electronic prescribing made verbal orders obsolete. But that’s not true. In operating rooms, trauma bays, and during rapid patient transfers, there’s no time to log into a computer. A surgeon needs to tell the nurse, "Give 10 milligrams of epinephrine IV now." A nurse in the ER has to confirm a dose of insulin before a diabetic patient goes into surgery. These aren’t convenience choices - they’re life-or-death necessities. According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, verbal orders still make up 10-15% of all medication orders in hospitals. In emergency departments, that number jumps to 25-30%. Even with CPOE systems in place, there are moments when typing isn’t fast enough. The key isn’t to ban them. It’s to control them.The Real Danger: Sound-Alike, Look-Alike Drugs

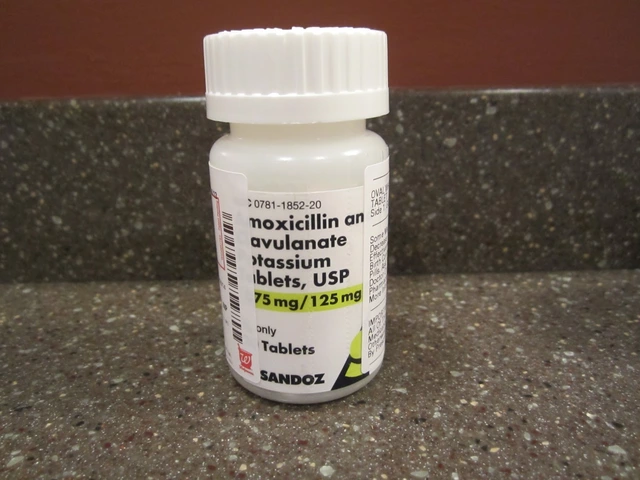

The biggest risk in verbal prescriptions isn’t bad handwriting. It’s bad hearing. Take these pairs:- Celebrex vs. Celexa - one’s for arthritis, the other for depression

- Zyprexa vs. Zyrtec - one’s an antipsychotic, the other an allergy pill

- Hydralazine vs. Hydroxyzine - one lowers blood pressure, the other treats anxiety

Read-Back: The One Rule That Saves Lives

There’s one practice that cuts verbal order errors in half. It’s not new. It’s not fancy. It’s just simple: read-back verification. Here’s how it works:- The prescriber gives the full order: "Give 5 milligrams of morphine IV every 4 hours for pain."

- The receiver repeats it back exactly: "Five milligrams of morphine IV every four hours for pain."

- The prescriber confirms: "Correct."

Numbers, Units, and the Two-Method Rule

A dose isn’t just "10." It’s "10 milligrams." Or "10 micrograms." The difference could kill someone. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices Canada says to say numbers two ways. For example:- "Fifteen milligrams. That’s one-five milligrams."

- "Two point five milligrams. That’s two and a half."

High-Alert Medications: When Verbal Orders Are Forbidden

Some drugs are too dangerous to order verbally - unless it’s a true emergency. The Pennsylvania Patient Safety Authority and Washington State Department of Health explicitly ban verbal orders for:- Chemotherapy (except to hold or discontinue)

- Insulin

- Heparin

- Opioids like morphine, fentanyl, oxycodone

Documentation: The Only Record That Matters

The only real record of a verbal order? The paper or screen it’s written on. Memories fade. People change shifts. Someone forgets. That’s why CMS and The Joint Commission require immediate transcription into the electronic health record. The order must include:- Patient’s full name and date of birth

- Medication name (spelled out)

- Dose with units (e.g., 5 mg, not just 5)

- Route (oral, IV, IM, etc.)

- Frequency (e.g., every 6 hours)

- Indication (why it’s being given - e.g., "for chest pain")

- Name and credentials of the prescriber

- Time and date the order was given

- Time and date it was authenticated

Who Can Enter the Order?

In 2022, CMS updated its rules to allow authorized documentation assistants - like nurses or medical assistants - to enter verbal orders into the EHR at the prescriber’s direction. But here’s the catch: only the prescriber can authenticate it. That means a nurse can type it in, but the doctor must review and sign off. No exceptions. No shortcuts. This isn’t about bureaucracy. It’s about accountability.

What to Do When Something Feels Off

You’re on the phone. The prescriber says, "Give 100 units of insulin." You pause. That’s not right. The patient’s blood sugar is normal. You don’t have a recent order for insulin. Don’t give it. Don’t ask, "Are you sure?" Ask, "Can you please confirm the dose and reason? I want to make sure I’m not missing something." Nurses on AllNurses.com report that asking for clarification has prevented multiple near-misses. One nurse said spelling out "hydralazine" as "H-Y-D-R-A-L-A-Z-I-N-E" stopped a 10-fold dosing error. Another said asking for the indication - "Why are we giving this?" - revealed the order was meant for a different patient. Trust your gut. If it feels wrong, it probably is.How to Build a Culture of Safety

No single rule fixes everything. Safety comes from culture. Hospitals that succeed with verbal prescriptions do three things:- Train everyone - doctors, nurses, aides - on the exact protocol. Not once. Every year.

- Use standardized scripts. "I’m giving a verbal order for [medication]. I’ll spell it out: [A-M-P-I-C-I-L-L-I-N]. Dose is [5 mg]. Route is IV. Frequency is every 6 hours. Indication is sepsis. Prescriber is Dr. Lee."

- Call out violations - respectfully. If a doctor skips read-back, say, "I need to hear it back to make sure I got it right." Make it normal. Make it expected.

What’s Next? The Future of Verbal Orders

Voice recognition tech is getting better. By 2025, KLAS Research predicts verbal orders will drop to 5-8% of total orders. But experts like Dr. Robert Wachter say some situations will always need spoken communication. Surgery. Trauma. Rural clinics with no internet. That means safety protocols aren’t going away. They’re becoming even more critical. The FDA is working on standardizing how high-risk drug names are pronounced. States are passing laws to make read-back mandatory. And hospitals are training staff to treat every verbal order like a ticking time bomb - because it is. The bottom line? Verbal prescriptions aren’t going to vanish. But they don’t have to be dangerous. With clear rules, disciplined practice, and a culture that values verification over speed, we can make them safe.Are verbal prescriptions still allowed in hospitals?

Yes. Verbal prescriptions are still permitted under CMS and The Joint Commission regulations, especially in emergencies, operating rooms, and during rapid patient transfers. However, they must follow strict safety protocols, including mandatory read-back verification and immediate documentation in the electronic health record.

What’s the biggest cause of errors in verbal prescriptions?

The biggest cause is sound-alike drug names. Medications like Celebrex and Celexa, or Hydralazine and Hydroxyzine, are frequently confused when spoken. This accounts for 34% of verbal order errors, according to the Institute for Safe Medication Practices. Always spell out drug names letter by letter to prevent these mistakes.

Is read-back verification really necessary?

Yes. Read-back verification - where the receiver repeats the order back to the prescriber - is mandatory under The Joint Commission standards and has been shown to reduce medication errors by up to 50%. Skipping it increases the risk of deadly mistakes. If you don’t hear it back, don’t assume it’s done.

Can you give verbal orders for insulin or heparin?

Only in true emergencies. Insulin, heparin, opioids, and chemotherapy are classified as high-alert medications. Most hospitals and state health departments prohibit verbal orders for these drugs unless the patient’s life is immediately at risk. Even then, a second healthcare provider must verify the dose before administration.

What should be included in the documentation of a verbal order?

Every verbal order must be documented immediately in the electronic health record and include: patient name and date of birth, medication name (spelled out), exact dose with units, route of administration, frequency, indication for use, prescriber’s name and credentials, time and date the order was given, and time and date it was authenticated by the prescriber.

Can a nurse enter a verbal order into the EHR?

Yes, but only under direct direction from the prescriber. A nurse or medical assistant can type the order into the system, but the prescriber must personally review and authenticate it. No one else can sign off on it. This ensures accountability and prevents unauthorized changes.

How can I improve safety when taking verbal orders?

Follow these steps: 1) Spell out every drug name. 2) Say numbers two ways (e.g., "fifteen milligrams, one-five milligrams"). 3) Never use abbreviations. 4) Always do read-back. 5) Document immediately. 6) Ask for clarification if anything feels off. 7) Speak up if protocols aren’t followed. Your vigilance can prevent a mistake.

Nilesh Khedekar

January 15, 2026 AT 18:19So let me get this right-we’re still relying on people’s ears to not mix up "Celexa" and "Celebrex" in a 3 a.m. code blue? And you call this medicine? I’ve seen nurses spell out drug names like they’re decoding a CIA cipher, and still, someone hands out the wrong pill because the EHR auto-filled the wrong one. This isn’t safety. It’s Russian roulette with IV bags.

Jami Reynolds

January 16, 2026 AT 03:15Have you considered that the real issue isn't verbal orders-but the fact that hospitals are now staffed by people who can't read a syringe, let alone spell "hydralazine"? The entire system is collapsing under the weight of credential inflation and lazy training. The FDA should mandate IQ tests for prescribers before they touch a keyboard-or a stethoscope.

Nat Young

January 16, 2026 AT 17:15Let’s be real-read-back works in theory, but in practice, it’s just a performative ritual. I’ve watched attendings bark out orders and nurses parrot them back like trained parrots, then immediately delete the order from the system and give the drug anyway. The documentation is a lie. The read-back is theater. And the patient? They’re just the audience.

Niki Van den Bossche

January 17, 2026 AT 17:13There’s a metaphysical dimension here, don’t you see? The verbal order is a sacrament-a fragile, whispered covenant between healer and healer, where language itself becomes the vessel of life or death. When we say "five milligrams," we’re not just transmitting data-we’re invoking fate. And yet, we treat it like a grocery list. We’ve lost the sacredness of the spoken word in medicine. The EHR is a cathedral of cold data, but the voice? The voice is where the soul of care still breathes.

Jan Hess

January 18, 2026 AT 12:30Love this breakdown. Seriously. The spell-it-out rule is simple but game-changing. I used to skip it too until I saw a guy almost get heparin instead of hydralazine because someone said "H-y-d" and the nurse heard "H-y-p". We started doing it on my unit and zero errors since. Just make it a habit. No big deal. Just do it.

Haley Graves

January 19, 2026 AT 13:33Every single nurse reading this needs to internalize one thing: If you’re not reading back, you’re not a nurse-you’re a liability. It’s not optional. It’s not inconvenient. It’s your job. And if your doctor gets annoyed when you ask them to repeat it? Good. That means they’re used to cutting corners. Don’t let them. Your patient’s life is not a suggestion.

Dan Mack

January 19, 2026 AT 20:50They say verbal orders are necessary but they never mention that 90% of these orders are given by doctors who are sleep-deprived, hungover, or on their third Percocet. The system isn’t broken-it’s designed to fail. Who really benefits? The drug companies. They profit from the chaos. The EHR? A money-making distraction. Read-back? A PR stunt. Wake up.

Sarah Mailloux

January 21, 2026 AT 04:41Just had a nurse ask me to spell "Zyprexa" the other day and I almost cried. After 12 years here, someone finally did it. We’ve been doing the read-back thing since 2018 and it’s made a real difference. Don’t overthink it. Say it. Hear it. Confirm it. Then move on. Simple. Effective. Human.

Amy Ehinger

January 21, 2026 AT 16:59I’ve been a med-surg nurse for 18 years and I can tell you-most of the time, the problem isn’t the order. It’s the environment. The beeping monitors, the 15 people yelling at once, the 30-minute delay in getting the EHR to load. I’ve had to repeat the same order three times just to get someone to hear me. No one’s talking about how broken the physical space is. We need quieter units. Fewer distractions. Maybe then we wouldn’t need all these rules.

RUTH DE OLIVEIRA ALVES

January 23, 2026 AT 05:16It is imperative to underscore that the documentation of verbal orders must adhere strictly to the regulatory mandates promulgated by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services and The Joint Commission. Any deviation, however minor, constitutes a breach of fiduciary duty and exposes the institution to actionable malpractice. The inclusion of the prescriber’s credentials, the explicit spelling of medication nomenclature, and the temporal authentication timestamp are not administrative formalities-they are the bedrock of legal and ethical accountability in clinical practice.

Crystel Ann

January 23, 2026 AT 22:37This made me think of my aunt who almost got the wrong insulin dose because the nurse didn’t spell out "U-100" and thought it was "100 units." She ended up in the ICU. I’m so glad someone’s finally writing this down. It’s not glamorous, but it’s the little things that keep people alive.

Diane Hendriks

January 23, 2026 AT 23:08Why are we letting American hospitals operate like third-world clinics? In Germany, verbal orders are banned unless the patient is actively coding-and even then, it’s recorded by two licensed physicians. We’re not just behind-we’re embarrassing ourselves. This isn’t innovation. It’s negligence dressed up as tradition.

ellen adamina

January 24, 2026 AT 20:15What about patients who are nonverbal or don’t speak English? Do they get the same protections? I’ve seen orders given in English to a Spanish-speaking nurse who nods along but doesn’t understand "milligrams" vs "micrograms." The system fails them too. We need multilingual protocols-not just for spelling, but for understanding.