Anticoagulant Dosing Calculator

Calculate appropriate DOAC dose based on kidney function. Based on current guidelines for patients with chronic kidney disease.

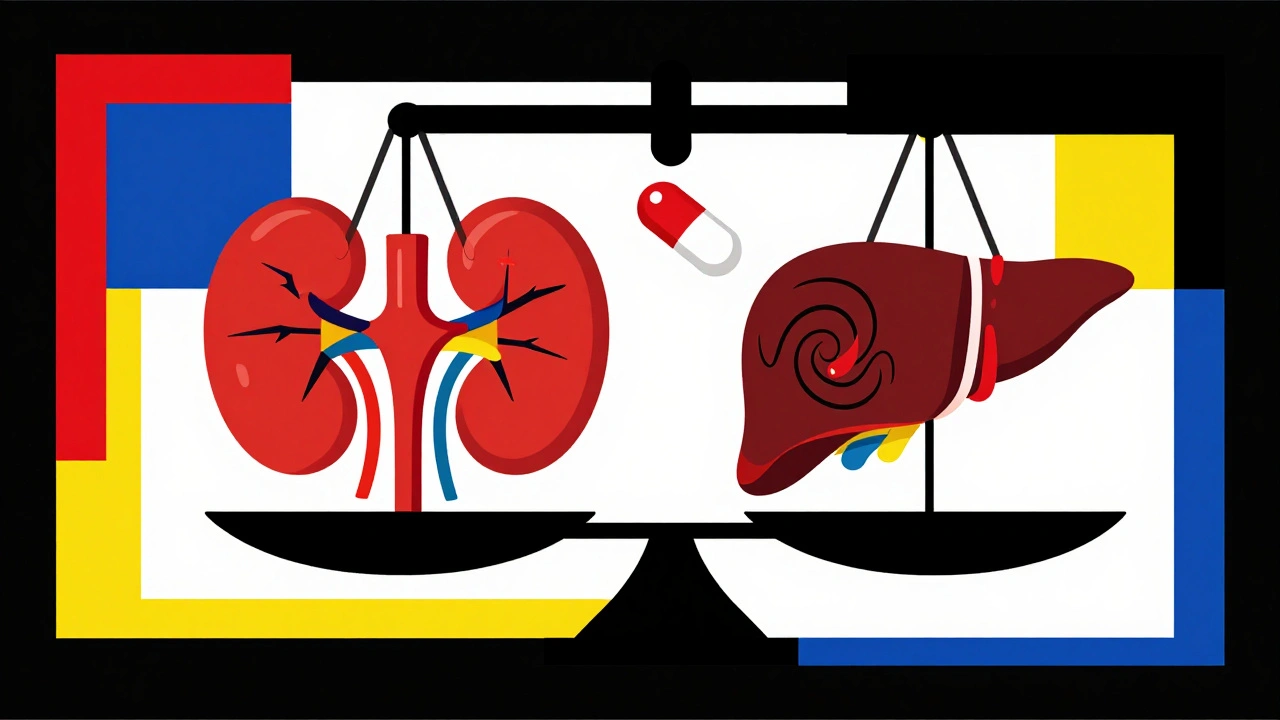

When someone has both kidney disease and liver disease, taking a blood thinner becomes one of the most dangerous balancing acts in medicine. It’s not just about avoiding clots-it’s about not bleeding out. This isn’t theoretical. In the U.S., over 5 million people with chronic kidney disease also have atrial fibrillation, and nearly 1 in 4 of them need a blood thinner. But most of the drugs we use were never tested in people with advanced organ damage. So what do doctors actually do when the guidelines don’t have answers?

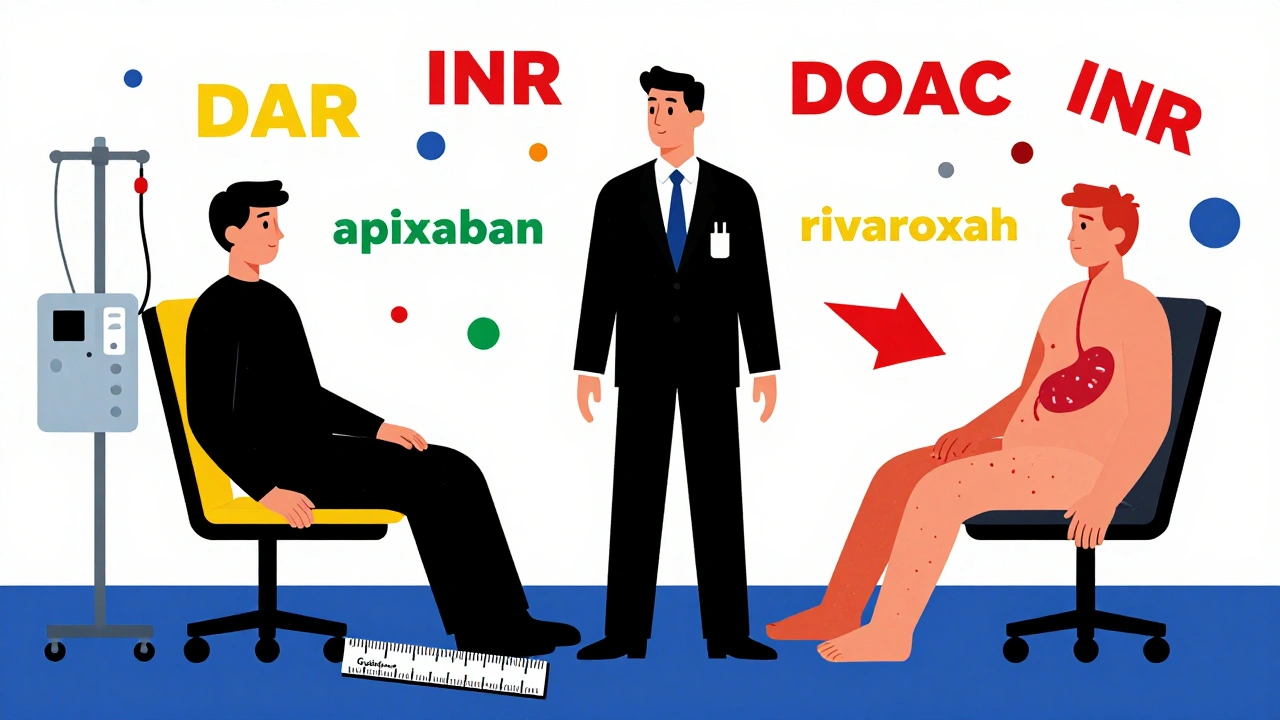

Why Standard Blood Thinners Don’t Work the Same Here

Most blood thinners today are direct oral anticoagulants, or DOACs-drugs like apixaban, rivaroxaban, dabigatran, and edoxaban. They replaced warfarin because they’re easier to use: no weekly blood tests, fewer food restrictions. But here’s the problem: every single major trial that proved these drugs were safe and effective excluded patients with severe kidney or liver disease. If your kidneys are barely working, or your liver is cirrhotic, you were left out. That means the data we rely on doesn’t apply to you.Take kidney disease. When your eGFR drops below 30 mL/min, your body can’t clear these drugs the way it should. Dabigatran? 80% of it leaves through the kidneys. That’s why it’s banned in advanced kidney disease. Rivaroxaban? About a third gets cleared by the kidneys, so it’s risky but sometimes used. Apixaban? Only 27% is cleared by the kidneys, which is why it’s the most commonly used DOAC in people with kidney failure-even though it wasn’t officially approved for that group.

Liver disease is even messier. Your liver doesn’t just make clotting factors-it also makes the proteins that stop clotting. In cirrhosis, both sides of the equation break down. You’re not just at risk for clots-you’re at risk for bleeding from a simple nosebleed. Platelet counts drop because the spleen swells. The INR, the test doctors use to monitor warfarin, becomes meaningless. Why? Because INR only measures vitamin K-dependent factors. It ignores everything else that’s broken: low fibrinogen, low platelets, poor clot strength. You can have an INR of 1.5 and still bleed like crazy.

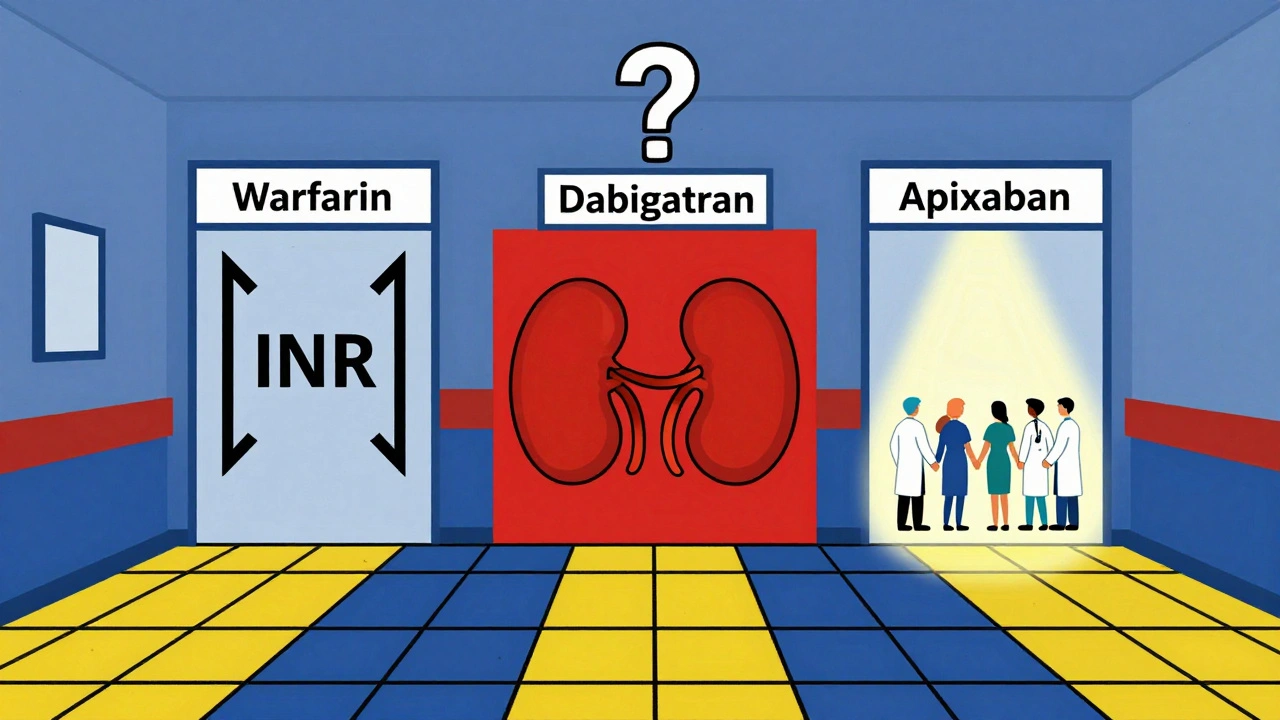

What Works in Kidney Disease? The Numbers Don’t Lie

For chronic kidney disease, the evidence is clearer than you might think. In stages 1 to 3a (eGFR ≥45), all DOACs are fine at standard doses. No changes needed. But once you hit stage 3b (eGFR 30-44), you need to cut the dose on some of them. Apixaban drops from 5 mg twice daily to 2.5 mg. Rivaroxaban goes from 20 mg to 15 mg. Edoxaban drops from 60 mg to 30 mg. These aren’t guesses-they’re FDA-mandated adjustments based on how much drug builds up in the blood.Now, for stage 4 and 5 kidney disease (eGFR <30), things get gray. The European Medicines Agency says: don’t use rivaroxaban or apixaban. The FDA says: apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is okay. Why the difference? Because in the ARISTOTLE trial, even in patients with eGFR under 30, apixaban had a 70% lower risk of major bleeding than warfarin. That’s not a small win. In dialysis patients, studies show apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily gives you a blood level around 47 ng/mL-less than half of what you’d see in someone with healthy kidneys. But it’s still enough to prevent strokes.

Warfarin? It’s still used-especially in dialysis patients with mechanical heart valves. But it’s harder to control. Your INR swings wildly. You might need blood tests every two weeks instead of once a month. And even then, you’re only in the target range 45% of the time, compared to 65% in people without liver or kidney disease.

Liver Disease: The INR Is a Lie

In liver disease, the biggest mistake doctors make is trusting the INR. If you have Child-Pugh Class C cirrhosis (the most severe), your INR is probably high-not because you’re over-anticoagulated, but because your liver can’t make clotting factors anymore. That doesn’t mean you’re at higher bleeding risk from the drug-it means the test is broken.So what do you do? The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases says: DOACs are okay in Child-Pugh A (mild disease). In Child-Pugh B (moderate), use them cautiously, maybe at lower doses. In Child-Pugh C? Avoid them. Why? Because in one study, patients with Child-Pugh C on DOACs had over five times the risk of major bleeding. That’s not a risk you take lightly.

But here’s the twist: some patients with cirrhosis develop portal vein thrombosis-a clot in the vein that carries blood to the liver. That’s life-threatening. And in those cases, the risk of not treating is worse than the risk of bleeding. So doctors sometimes use DOACs anyway, even in Child-Pugh B or C, because the clot could kill them faster than a bleed. It’s not about the numbers. It’s about the story.

Some hospitals now use TEG or ROTEM-tests that show how well the whole clotting system works, not just one part. But only 38% of U.S. hospitals have them. Most still rely on the INR. And that’s dangerous.

Apixaban: The Least Bad Option

If you have to pick one DOAC for kidney and liver disease, apixaban comes out on top. Why? Three reasons. First, it’s the least dependent on the kidneys. Second, it’s the safest in head-to-head comparisons. In patients with eGFR under 30, apixaban cut major bleeding by 31% compared to warfarin. Third, it’s the only DOAC with real-world data in dialysis patients. A 2021 registry of over 12,000 dialysis patients showed DOACs had fewer bleeds than warfarin-14.2 events per 100 patient-years versus 18.7.But it’s not perfect. One nephrologist on Reddit reported 15 dialysis patients on apixaban 2.5 mg daily with zero bleeds over two years. Another described a patient who bled to death from a retroperitoneal hemorrhage on the same dose. That’s the reality. There’s no guarantee. Just better odds.

And yes, there’s a cost. Reversing apixaban costs $19,000 for a single dose of andexanet alfa-and only 45% of U.S. hospitals have it. Idarucizumab, which reverses dabigatran, is cheaper at $3,500, but you can’t use it for apixaban. So if you’re on apixaban and you bleed, you’re relying on supportive care: transfusions, pressure, time. No magic antidote.

What About New Drugs and Guidelines?

There’s hope on the horizon. The MYD88 trial is currently randomizing 500 dialysis patients to either apixaban or warfarin. Results are due in 2025. That’s the first real RCT in this population. Until then, we’re guessing. The LIVER-DOAC registry is tracking 1,200 cirrhotic patients on DOACs worldwide. Early data suggests DOACs are safe in Child-Pugh A and B if you’re careful.KDIGO, the global kidney health group, is updating its guidelines in late 2024. They’ll include 17 new observational studies. That’s not a randomized trial-but it’s more than we had. The FDA is also considering adding apixaban labeling for end-stage kidney disease based on modeling, not just trial data.

And yet, 78% of U.S. hospitals still don’t have a written protocol for anticoagulating patients with both kidney and liver disease. That means decisions are made on the fly-by whoever is on call. And that’s why medication errors are 3.2 times more common in this group.

How Doctors Actually Decide

Here’s what happens in real clinics, not on paper. For a patient with stage 4 kidney disease and mild cirrhosis, the nephrologist and hepatologist sit down. They check the platelet count. If it’s under 50,000, they’re nervous. They look at the MELD score-if it’s above 20, they’re worried. They check if the patient has had a bleed before. If yes, they avoid DOACs. If no, they might try apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily.They don’t just check the eGFR. They look at trends. Is the kidney function dropping fast? Then they monitor every month. Is the liver stable? Then they check platelets every three months. They don’t trust the INR. They ask: has the patient had a nosebleed? Black stools? Unexplained bruising? They treat symptoms, not numbers.

And they always ask: why are we giving this drug? Is it for atrial fibrillation? Then stroke risk is the main concern. Is it for a clot in the liver vein? Then the risk of death from the clot is higher than the risk of bleeding. That changes everything.

What You Can Do

If you or someone you care about has kidney or liver disease and needs a blood thinner:- Ask: What’s my eGFR? And is it stable or dropping?

- Ask: What’s my Child-Pugh or MELD score? Don’t let them skip this.

- Ask: Is my platelet count below 50,000? If yes, that changes the game.

- Ask: Why are we using this drug? Stroke prevention? Clot treatment? The answer changes the risk-benefit.

- Ask: What happens if I bleed? Does the hospital have a reversal agent? Do they know how to manage it?

- Ask: Who’s in charge? Is there a nephrologist and hepatologist working together? If not, ask for a consult.

There’s no perfect answer. But there are better ones. Apixaban is the safest bet for most. Warfarin still has a place. And sometimes, the best decision is to not use anything at all-if the bleeding risk outweighs the clot risk.

What’s clear is this: if you have both kidney and liver disease, you need more than a prescription. You need a team. You need to be heard. And you need to know that your doctor isn’t just following a guideline-they’re making a judgment call in the dark. Your job is to make sure they’re not guessing alone.

Can I take apixaban if I’m on dialysis?

Yes, apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is the most commonly used blood thinner in dialysis patients, even though it wasn’t originally approved for this group. Studies show it has lower bleeding risk than warfarin and still prevents strokes. But it’s not risk-free-some patients still bleed. Your doctor should monitor you closely and only use it if your kidney function is stable and you don’t have a history of major bleeding.

Is warfarin safer than DOACs in liver disease?

Not necessarily. Warfarin has a known reversal agent (vitamin K and fresh frozen plasma), but its INR is unreliable in cirrhosis. You can have a normal INR and still bleed badly. DOACs like apixaban don’t rely on INR and have lower rates of brain bleeds. In Child-Pugh A or B cirrhosis, DOACs are often preferred. Only in Child-Pugh C or if you have a mechanical heart valve is warfarin still the standard.

Why is dabigatran not used in kidney disease?

Dabigatran is cleared 80% by the kidneys. In advanced kidney disease (eGFR <30), the drug builds up to dangerous levels, increasing bleeding risk dramatically. It’s officially contraindicated in this group. Even in moderate kidney disease, it’s avoided because its clearance drops so sharply. Apixaban and rivaroxaban are better choices because they’re cleared more by the liver.

Can I take a blood thinner if my platelets are low?

It depends. If your platelets are below 50,000/μL, most doctors will pause or avoid anticoagulation unless the clot risk is extremely high-like a clot in the liver vein. Low platelets mean you’re more likely to bleed. Some hospitals use TEG or ROTEM to check clot strength before deciding. If you’re on a DOAC and your platelets drop, your doctor will likely stop it and reassess.

What if I’m on both kidney and liver disease?

This is the hardest scenario. You need both a nephrologist and hepatologist involved. Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily is usually the first choice because it’s least dependent on both organs. Your doctor will check your eGFR, MELD score, platelet count, and history of bleeding. If your kidney function is declining fast or your liver disease is worsening, they may avoid anticoagulation entirely. The goal isn’t to follow a guideline-it’s to prevent death, whether from a clot or a bleed.

There’s no one-size-fits-all answer. But if you’re being treated for kidney or liver disease and need a blood thinner, ask the right questions. Push for a team approach. Don’t accept a prescription without understanding why it’s being chosen. Because in this space, the difference between life and death isn’t just the drug-it’s the decision behind it.

James Moore

December 5, 2025 AT 21:17Look, I get it-medicine is a mess, and the FDA’s guidelines are written by people who’ve never seen a real patient with end-stage liver and kidney failure. We’re treating numbers, not humans. DOACs? They’re corporate toys, not medical miracles. The trials excluded the sickest people because they didn’t want messy data, and now we’re left guessing while patients bleed out in ERs. This isn’t science-it’s liability management dressed up as progress. And don’t even get me started on how insurance companies dictate dosing based on cost, not clinical need. We’ve turned healing into a spreadsheet.

Chris Brown

December 5, 2025 AT 23:50It is deeply concerning that the medical establishment continues to rely on data that explicitly excludes the most vulnerable populations. The ethical implications are not merely theoretical; they are systemic and pervasive. One cannot ethically prescribe a drug whose pharmacokinetics have not been validated in the very cohort that requires it most. This is not innovation-it is negligence masked as convenience.

Laura Saye

December 6, 2025 AT 15:57I’ve seen this play out in clinic after clinic-patients terrified to take anything, doctors paralyzed by guidelines that don’t fit. It’s not that we don’t care-it’s that we’re handed tools designed for a different world. Apixaban gets used in stage 5 CKD not because it’s perfect, but because it’s the least bad option. And yet, we don’t talk about the fear in the patient’s eyes when they ask, ‘Will this kill me?’ We need more real-world data, not just trial numbers. We need to listen to the people living this, not just the papers.

Krishan Patel

December 8, 2025 AT 03:22What a disgrace. Western medicine has become a profit-driven farce. You think they care about patients? No. They care about lawsuits. That’s why they exclude the elderly, the renal, the cirrhotic-from every trial. Then they sell you a pill and say ‘it’s safe.’ Meanwhile, in India, we’ve been using low-dose warfarin with INR monitoring for decades in cirrhotic patients-successfully. But no, the West needs their fancy DOACs, even if they’re useless. This isn’t medicine. It’s capitalism with a stethoscope.

Carole Nkosi

December 9, 2025 AT 04:22Let’s be real-no one wants to admit they don’t know what to do. So they push apixaban like it’s magic. But if your liver can’t make clotting factors and your kidneys can’t clear the drug, you’re not being treated-you’re being experimented on. And the worst part? You’re told you’re lucky to have options. No. You’re lucky you haven’t bled out yet.

Mark Curry

December 10, 2025 AT 11:10Yeah, this is rough. I’ve had patients on apixaban 2.5mg with eGFR 20 and they’re fine… but you never know. It’s a gamble. I just try to keep it simple-lowest dose possible, watch for bruising, avoid NSAIDs. Sometimes that’s all you can do. :/

Manish Shankar

December 12, 2025 AT 05:09It is imperative to acknowledge that the pharmacodynamic alterations observed in patients with concurrent renal and hepatic insufficiency necessitate a paradigm shift away from standardized dosing protocols. The current reliance on eGFR thresholds, while clinically pragmatic, fails to account for the dynamic interplay between synthetic dysfunction, protein binding, and non-renal clearance pathways. A personalized, biomarker-driven approach, incorporating thromboelastography and platelet function assays, may offer a more robust framework for clinical decision-making.

Rupa DasGupta

December 13, 2025 AT 04:36Wait… so you’re telling me the drugs they gave my uncle were never tested on people like him? And now he’s in the hospital with a brain bleed? 😭 That’s not science. That’s a crime. Who’s paying for this? Pharma? Who’s letting them get away with it? I’m calling my senator.

Marvin Gordon

December 13, 2025 AT 06:54Man, this is the stuff nobody talks about. I’ve been in ICU with guys who had INR 1.2 and were oozing from every IV site. The system’s broken, but we’re still showing up. We adjust, we monitor, we talk to families. It’s messy. It’s scary. But we do it. And yeah, apixaban’s our best shot right now-even if it’s not perfect. Keep pushing for better data. But don’t stop treating people while we wait.

ashlie perry

December 15, 2025 AT 03:17they're all just testing on the poor

Juliet Morgan

December 16, 2025 AT 18:56You’re not alone in feeling this way. I’ve had families cry because they didn’t know their dad was basically a guinea pig. It breaks my heart. But we’re learning. Slowly. And we’re listening. Keep speaking up-it’s how things change. You’re doing important work just by caring.