Why Are Generic Drugs So Often Out of Stock?

You walk into the pharmacy for your blood pressure pill, your antibiotic, or your chemotherapy drug-only to be told it’s out of stock. Not just delayed. Out of stock. And it’s happened before. And it’ll happen again. This isn’t bad luck. It’s the system.

Generic drugs make up 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. They’re cheap, effective, and essential. But they’re also the most likely to disappear from shelves. In fact, 95% of all drug shortages reported in the U.S. and Canada involve generics. And the reason isn’t one thing-it’s a chain of failures, all tied to how these drugs are made, sold, and shipped.

Manufacturing Problems Are the #1 Cause

Over 60% of all drug shortages come down to one thing: manufacturing failures. Not because factories are old. Not because workers are lazy. But because the standards are so strict, and the margins are so thin, that even a small mistake can shut everything down.

A single batch of sterile injectable medicine gets contaminated with a speck of dust? The whole facility shuts down for months. Equipment breaks? No backup machine? Production stops. The FDA finds a compliance issue during an inspection? The plant can’t ship anything until it fixes everything. And these fixes aren’t cheap. They cost millions.

Here’s the catch: most generic drug makers operate on razor-thin profit margins-often under 15%. Compare that to branded drugs, which can make 30-40% profit. So when a factory has to spend $5 million to upgrade its filters or replace a sterilizer, it’s not just a cost. It’s a risk. Many just decide: Let’s stop making this drug.

Since 2010, over 3,000 generic products have been discontinued. And the trend is accelerating. Why? Because no one’s paying enough to make it worth the risk.

Global Supply Chains Are Fragile

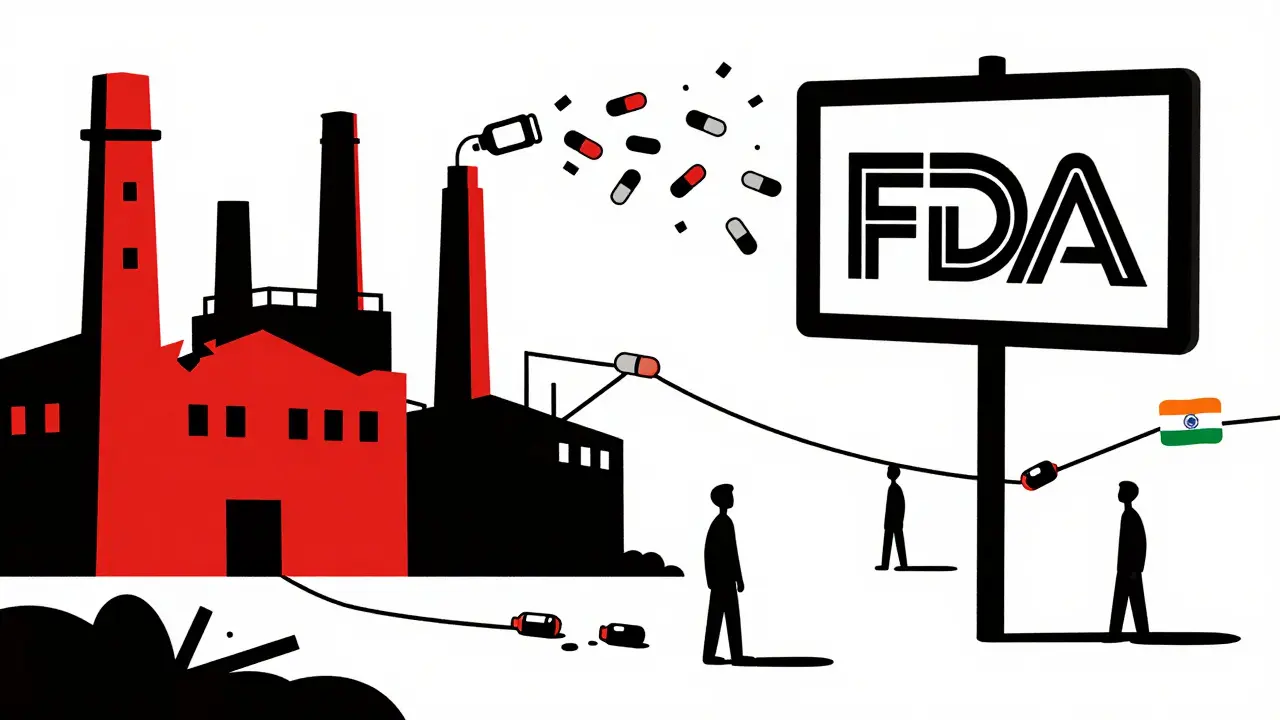

Think about where your pills come from. About 80% of the active ingredients (APIs) in generic drugs are made in just two countries: China and India. That’s not diversity. That’s a single point of failure.

When a flood hit a major API plant in India in 2021, hundreds of drugs vanished from U.S. pharmacies. When China locked down during the pandemic, the supply of antibiotics, painkillers, and cancer drugs stalled. These aren’t rare events. They’re predictable.

And there’s almost no backup. Most generic drugs are made by just one or two manufacturers. If one shuts down, there’s no one else to pick up the slack. That’s called “sole sourcing.” One in five drug shortages is caused by a single supplier failing.

Even when other factories exist, they’re not ready to scale up. They don’t have the licenses. They don’t have the staff trained on that specific process. And getting FDA approval for a new supplier can take 18 months. By then, patients are already going without.

No Extra Capacity Means No Buffer

Most industries keep extra inventory. Car factories keep spare parts. Grocery stores keep extra milk. But drug manufacturers? They run lean. Like, dangerously lean.

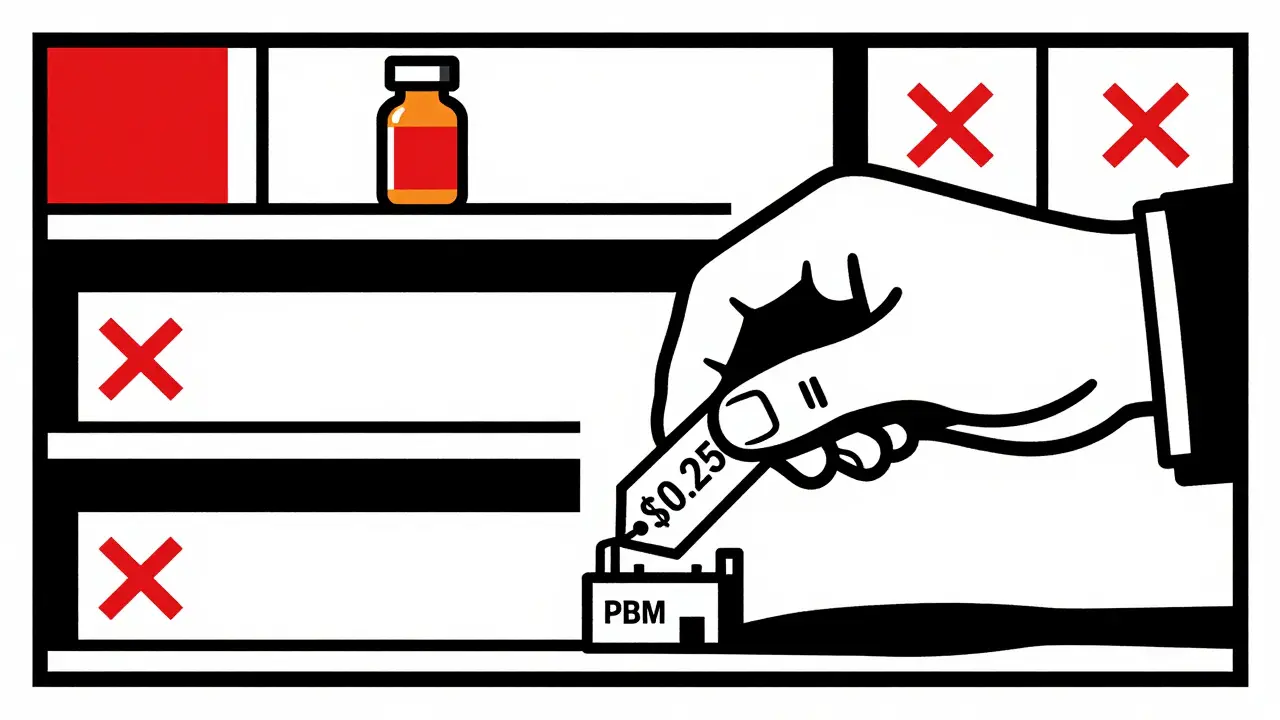

Why? Because they’re pressured to keep prices low. Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-the middlemen who control 85% of prescription spending-negotiate the lowest possible price. To compete, manufacturers cut everything: staffing, maintenance, safety margins, and especially excess capacity.

There’s no spare machine. No extra batch sitting in a warehouse. No buffer. So when a machine breaks, or a shipment gets delayed at customs, or a supplier runs out of raw material, there’s nothing to fall back on. One hiccup becomes a nationwide shortage.

This isn’t smart business. It’s a gamble. And patients are the ones who lose.

Profit Margins Are Collapsing

Generic drugs were supposed to save money. And they did. But now, the system is eating itself.

As more companies enter the market, prices keep dropping. A drug that sold for $10 a pill in 2015 might now sell for $0.25. That’s great for insurers. But for the manufacturer? It’s not enough to cover the cost of running a clean, FDA-compliant facility.

Some companies just quit. Others keep producing, but cut corners. They use cheaper raw materials. They reduce quality checks. They delay maintenance. That leads to more contamination events. More shutdowns. More shortages. It’s a vicious cycle.

And it’s getting worse. Fewer new companies are entering the generic market. Why? Because the returns are too low. The risks are too high. The FDA approves new manufacturers, but they can’t compete with the price-cutting race.

Meanwhile, the U.S. market is dominated by just a few big players. Three PBMs control most of the buying power. They don’t care about supply stability. They care about the lowest bid. And manufacturers? They’re stuck in the middle.

Why Canada Handles This Better

Canada has the same problems: global supply chains, low margins, single-source drugs. But their shortages are less frequent and less severe.

Why? Because they don’t leave it to the market.

Canada has a national pharmaceutical stockpile-specifically for routine drug shortages, not just pandemics or disasters. They track inventory across hospitals. They share data between regulators, manufacturers, and pharmacies. When a shortage hits, they don’t wait. They coordinate.

They also pay manufacturers fairly. Not the lowest price. A price that covers costs and allows for stability. That means companies are more likely to stay in the game, even for low-volume drugs.

The U.S. doesn’t have that. The Strategic National Stockpile only kicks in for bioterrorism or natural disasters. Not for a shortage of insulin or heart medication. So when a drug vanishes, hospitals scramble. Pharmacists spend half their day calling other pharmacies, trying to find a substitute. Doctors delay treatments. Patients suffer.

What’s Being Done? Not Enough

There are signs of change. In 2023, Congress introduced the RAPID Reserve Act. It proposes creating a federal stockpile of critical generic drugs. It also offers incentives for domestic manufacturing. That’s a start.

The FTC is also investigating PBMs. Their interim report called out the lack of transparency and the power these middlemen hold over drug access. That’s important. But investigations take years. And by then, more patients will go without.

The American Medical Association now advises hospitals not to favor drugs that are in short supply over those that are available. That’s common sense. But it’s not policy. It’s just a suggestion.

Until we fix the economics-until we pay manufacturers enough to stay in business, until we build real redundancy into the system, until we stop treating life-saving drugs like commodities-we’ll keep seeing the same headlines: Drug shortage. No alternative. Patients at risk.

What This Means for Patients

You might think, ‘I don’t take generics.’ But you probably do. Or someone you love does. Antibiotics. Blood pressure meds. Chemo. Insulin. These are all available as generics-and all have been in short supply.

When a drug disappears, doctors have to switch treatments. That means new side effects. New interactions. New tests. Delays. Extra costs. Stress.

One hospital pharmacist told researchers they now spend 50-75% more time managing shortages than they did 10 years ago. That’s not just inconvenient. It’s dangerous.

And here’s the worst part: in one out of four cases, no one knows why the drug is gone. No explanation. No timeline. Just silence.

Patients deserve better. The system is broken. And it’s not because of bad people. It’s because the rules are written for profit-not for people.

Daz Leonheart

February 3, 2026 AT 18:15Amit Jain

February 3, 2026 AT 20:07Demetria Morris

February 5, 2026 AT 14:20Geri Rogers

February 5, 2026 AT 23:53Caleb Sutton

February 7, 2026 AT 09:10Jamillah Rodriguez

February 9, 2026 AT 02:41Susheel Sharma

February 10, 2026 AT 05:21Janice Williams

February 11, 2026 AT 05:01Prajwal Manjunath Shanthappa

February 13, 2026 AT 02:16Wendy Lamb

February 13, 2026 AT 13:19Antwonette Robinson

February 14, 2026 AT 15:45Katherine Urbahn

February 15, 2026 AT 06:31