When you or a loved one needs a simple, life-saving generic drug-like an antibiotic, an anesthetic, or a chemotherapy agent-and the pharmacy has none in stock, it’s not a glitch. It’s a systemic failure. Generic drugs make up over 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., yet they’re the source of 95% of all drug shortages. Why? Because the system that makes these cheap medicines is breaking down, and the cracks are showing up in hospitals, clinics, and home medicine cabinets.

Manufacturing Problems Are the Biggest Cause

The single biggest reason generic drugs disappear from shelves isn’t a lack of demand-it’s a lack of reliable manufacturing. According to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), over 60% of all drug shortages between 2010 and 2023 were caused by manufacturing or quality issues. These aren’t minor delays. They’re full production halts.

Think about it: a single contaminated batch of sterile injectable can shut down an entire facility for months. Contamination from mold, bacteria, or even tiny particles in the air can force a plant to close for deep cleaning and regulatory review. Equipment failures, power outages, or worker shortages add to the problem. And because many of these facilities are old and running at full capacity with no spare room, one breakdown can ripple across dozens of drugs.

One major manufacturer might produce 50 different generic drugs from one plant. If that plant shuts down, patients needing five different medications all face delays. No backup. No alternative. Just silence.

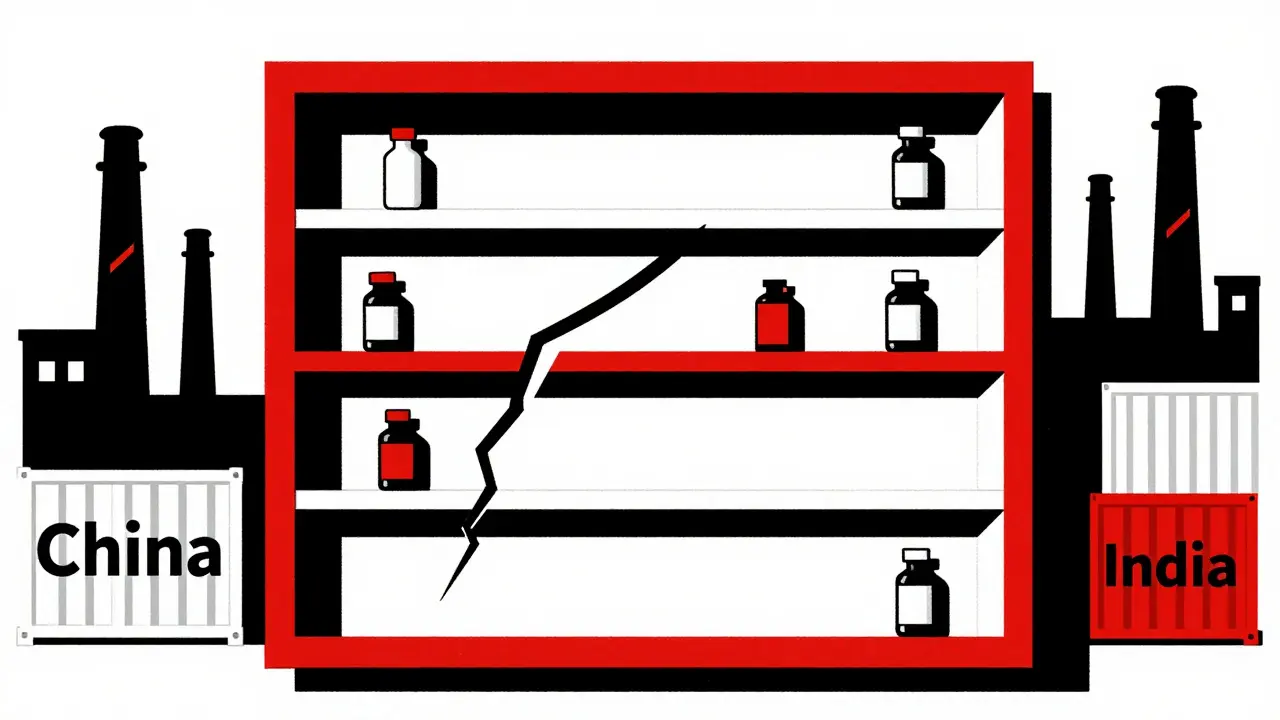

Global Supply Chains Are Fragile

Most of the active ingredients in generic drugs-called APIs (active pharmaceutical ingredients)-are made in just two countries: China and India. Around 80% of global API production happens there. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a cost-saving strategy that backfired.

When a factory in India gets hit by a monsoon, or a chemical plant in China faces new environmental regulations, the ripple effect hits U.S. hospitals within weeks. There’s no local stockpile. No domestic backup. And because the U.S. relies on just-in-time delivery, there’s no buffer. If a shipment is delayed at customs or a port worker goes on strike, the drug vanishes.

Even worse, many critical drugs are sole-sourced. That means only one company in the world makes them. If that company has a problem, there’s no other supplier to step in. One in five drug shortages reported to the FDA involve a sole-sourced product. For drugs like injectable epinephrine or certain cancer treatments, that’s terrifying.

Profit Margins Are Too Low to Sustain Production

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. And they are. But that’s part of the problem. While branded drugs can carry 30-40% profit margins, generics often make less than 15%. Some barely break even.

Manufacturers have to cover the cost of maintaining FDA-compliant facilities, training staff, running quality tests, and updating equipment-all while competing with others who slash prices to win contracts. The result? Companies stop making low-margin drugs. They shut down production lines. They exit the market entirely.

Since 2010, over 3,000 generic products have been discontinued. Many of them were essential medicines with low sales volume but high clinical need. A drug used by 10,000 people a year might be more profitable to abandon than to keep making. And once a manufacturer leaves a market, it’s hard to come back. The FDA approval process for a new facility takes years. No one wants to invest in a product that might be priced out of existence next year.

Market Concentration Is Making Things Worse

It’s not just manufacturers. The middlemen have too much control. Three pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs)-companies that negotiate drug prices for insurers and employers-control about 85% of prescription drug spending in the U.S. They decide which drugs get covered, which get pushed to the back of the line, and which get dropped entirely.

These companies don’t always choose drugs based on what’s best for patients. They choose based on rebates and kickbacks. A drug that costs $10 but offers a $3 rebate might get priority over a drug that costs $8 with no rebate-even if the $8 drug is in steady supply. This creates perverse incentives. Manufacturers are pressured to lower prices further just to stay in the game. And when they can’t, they stop making the drug.

The Federal Trade Commission called this system “opaque and unaccountable.” Hospitals and pharmacists have no say. Patients have no visibility. And when a drug shortage hits, no one knows why it happened-or who’s to blame.

No Redundancy, No Safety Net

Unlike other industries, pharmaceutical supply chains don’t build in backups. There’s no spare tire. No extra warehouse. No dual-sourcing strategy. Most manufacturers operate with zero excess capacity. They run factories at 95% utilization because it’s cheaper.

That’s fine until something breaks. A power outage. A regulatory inspection. A pandemic. When those happen, there’s no cushion. No way to ramp up production quickly. And because so many drugs are made in just one or two places, the whole system becomes a house of cards.

Compare this to Canada. Canada has a national stockpile of critical drugs. It coordinates between regulators, hospitals, and manufacturers. When a shortage hits, they redistribute supplies across provinces. The U.S. doesn’t do this. Its Strategic National Stockpile is only for bioterrorism or mass disasters-not routine drug shortages.

What’s Being Done? Not Enough

There are proposals. The RAPID Reserve Act, introduced in 2023, wants to create a federal reserve of critical generic drugs and offer tax breaks to companies that manufacture them domestically. The FDA is pushing for better transparency-requiring manufacturers to report potential shortages earlier. The AMA is calling for reforms to stop PBMs from pushing out drugs that are in supply just because they’re less profitable.

But none of these fix the root issue: the economic model is broken. As long as generic drugs are treated as commodities instead of essential public health tools, shortages will keep happening. And they’ll keep hitting the most vulnerable: cancer patients, ICU patients, diabetics, people on antibiotics for life-threatening infections.

The truth? We can’t outsource our medicine supply to two countries and expect it to be reliable. We can’t let a handful of middlemen decide who gets access to life-saving drugs. And we can’t keep pretending that low prices are the only metric that matters when people’s lives are on the line.

It’s Not Just a U.S. Problem

Studies from the University of Toronto and the University of Pittsburgh show that Canada and the U.S. face nearly identical supply chain problems. But Canada’s response is different. It’s coordinated. It’s transparent. It’s designed for people, not profits.

The U.S. system is built for efficiency, not resilience. And in a world where a single factory shutdown can leave thousands without treatment, efficiency isn’t enough. We need redundancy. We need transparency. We need to treat essential medicines like the public health infrastructure they are-not just another line item in a corporate ledger.

Until then, the next time you hear a pharmacy say, "We’re out of this drug," remember: it wasn’t an accident. It was a design flaw.

Why do generic drug shortages happen more often than branded drug shortages?

Generic drugs are cheaper, which means lower profit margins for manufacturers. Companies often stop making them because they can’t make enough money to cover the cost of maintaining FDA-compliant facilities. Branded drugs, by contrast, have patent protection and higher prices, so manufacturers invest more in reliable production and backup supply chains.

Are drug shortages getting worse?

Yes. Between 2018 and 2023, 2018 saw the highest number of drug shortages on record, followed closely by 2020 during the pandemic. Since then, the number hasn’t dropped. In fact, experts warn that shortages are becoming more frequent and longer-lasting due to increased global supply chain fragility and declining manufacturing capacity.

Why are most generic drugs made in China and India?

Manufacturing costs are significantly lower in those countries, and they’ve built large-scale API production facilities over the last 20 years. The U.S. and Europe phased out much of their generic manufacturing because it wasn’t profitable. Now, the U.S. imports over 80% of its active ingredients from just two countries, making the supply chain vulnerable to political, environmental, or economic disruptions.

What role do pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) play in drug shortages?

PBMs control about 85% of U.S. prescription drug spending. They negotiate rebates from manufacturers and decide which drugs are covered on insurance formularies. Sometimes, they favor drugs with higher rebates-even if those drugs are in short supply-while dropping drugs that are readily available but offer no rebate. This distorts the market and encourages manufacturers to abandon low-margin, high-need drugs.

Can the U.S. build domestic manufacturing for generics?

Yes, but it’s expensive and slow. Building a single FDA-approved manufacturing facility for generics can cost over $200 million and take 5-7 years. Without government incentives-like tax breaks, guaranteed purchases, or subsidies-private companies won’t risk the investment. Bills like the RAPID Reserve Act aim to change that, but they’re still in early stages.

What happens to patients when a drug is in shortage?

Patients face delays in treatment, risky substitutions with less effective or more toxic alternatives, or even no treatment at all. Hospital pharmacists report spending up to 75% more time managing shortages than they did 15 years ago. In cancer care, chemotherapy shortages have led to treatment delays that reduce survival rates. For critically ill patients, even a few days without a drug can be life-threatening.

Amit Jain

February 4, 2026 AT 09:32Simple truth: we outsourced our medicine to save a few bucks. Now we pay with lives. India and China make the pills, but when monsoons hit or politics get messy, Americans suffer. We need domestic production-no excuses.

Joseph Cooksey

February 5, 2026 AT 00:25Let’s be real-this isn’t just about manufacturing or supply chains. It’s about the entire American healthcare ethos being built on exploitation. We treat life-saving drugs like commodities, not rights. We reward corporations for cutting corners, penalize them for investing in safety, and then act shocked when people die because a factory in Gujarat had a power outage. We don’t have a drug shortage crisis-we have a moral bankruptcy crisis. And no, tax breaks won’t fix it. We need to restructure the entire system so profit isn’t the only god we worship. Until then, every time a nurse scrambles for a substitute for a missing chemo drug, she’s not just doing her job-she’s patching a system that was designed to fail.

Keith Harris

February 6, 2026 AT 22:19Oh please. This is all just woke corporate guilt. The real problem? The FDA’s insane regulations. They make it so expensive and slow to build plants that no one wants to invest. Meanwhile, China just builds factories and ignores environmental rules. We’re not losing drugs to globalization-we’re losing them to bureaucracy. Let’s deregulate and watch supply fix itself.

Kunal Kaushik

February 7, 2026 AT 01:17Yikes 😔 I work in a hospital pharmacy in Delhi. We see the same problems-when U.S. orders drop, our factories cut shifts. People here lose jobs. People there lose meds. It’s all connected. We need global cooperation, not blame. 🌍❤️

Mandy Vodak-Marotta

February 7, 2026 AT 11:39Okay but can we talk about how wild it is that we’ve got people in ICU waiting for epinephrine because some PBM decided a $0.20 rebate on a different drug was more profitable? Like… what even is our system?? I had a friend whose dad missed his chemo dose for three weeks because the generic version was ‘unavailable’-and the hospital had to scramble to get a branded version at 10x the cost. That’s not healthcare. That’s a horror show with a side of insurance forms.

Alec Stewart Stewart

February 7, 2026 AT 18:14This is heartbreaking. I’ve seen it firsthand-my mom’s blood pressure med disappeared for six months. We had to switch to something that made her dizzy and nauseous. No one explained why. No one apologized. Just a shrug from the pharmacist. We treat medicine like a commodity, but it’s not. It’s oxygen for people who are already barely breathing. We need to start treating it that way.

Caleb Sutton

February 8, 2026 AT 18:43They’re poisoning our drugs on purpose. The FDA and Big Pharma are in cahoots. They want you dependent on expensive branded meds. The shortages? Staged. To scare you into buying the overpriced stuff. Don’t fall for it.

Jamillah Rodriguez

February 9, 2026 AT 15:28Ugh. Another ‘deep dive’ on drug shortages. Can we just… not? I just want my antibiotics without a 3-week wait. That’s it. That’s the tweet.

Katherine Urbahn

February 10, 2026 AT 22:33It is imperative to underscore, with unequivocal clarity, that the structural deficiencies in the American pharmaceutical supply chain are not merely operational-they are ethically indefensible. The absence of redundancy, the commodification of essential therapeutics, and the systemic prioritization of profit over patient welfare constitute a dereliction of public trust of monumental proportion. Regulatory reform is insufficient; we require a paradigmatic shift toward the recognition of pharmaceutical access as a fundamental human right.

Meenal Khurana

February 11, 2026 AT 07:40My factory in Mumbai made 30% of the world’s metformin. We shut down for three months after a fire. No one in the U.S. asked why.

Jesse Naidoo

February 13, 2026 AT 04:54Why don’t you just go to Canada? They’ve got it all figured out. Wait, you can’t? Oh right. Because your insurance won’t cover it. Classic.

Sherman Lee

February 13, 2026 AT 19:40China’s got the supply. India’s got the labs. But who’s really pulling the strings? The same people who control the Fed, the FDA, and the Pentagon. They want you dependent. They want you weak. This isn’t about drugs-it’s about control. And the next shortage? It’s already planned. 🤫💣

Lorena Druetta

February 14, 2026 AT 15:10Every single person reading this has a story about a medication that disappeared. My brother waited 47 days for his insulin. He lost 18 pounds. He nearly died. We are not a country that values life when it’s inconvenient. We must demand better. Not someday. Now.

Zachary French

February 16, 2026 AT 12:41Y’all act like this is new? The FDA’s been screwing with generic approvals since 2008. And PBMs? They’re the real villains. I work in pharma logistics-trust me, the ‘shortages’ are often just accounting tricks to push higher-margin junk. And don’t even get me started on how they ‘lose’ shipments on purpose. It’s all a scam. But hey, at least your co-pay’s low right? 😒

Daz Leonheart

February 16, 2026 AT 21:49It’s not hopeless. We’ve got people working on solutions-local compounding pharmacies, state-level stockpiles, even community-run drug banks. It’s slow, but it’s real. You don’t need a federal bill to start helping. Help someone today. Share a pill. Call your rep. Write a letter. Change starts small.