Most people assume that when a pharmaceutical company gets a patent on a new drug, they have 20 years to sell it without competition. That’s not true. In reality, the actual time a drug stays on the market with no generics-what’s called effective patent life-is often just 10 to 13 years. And sometimes, it’s even less.

Why the 20-Year Patent Doesn’t Mean 20 Years of Sales

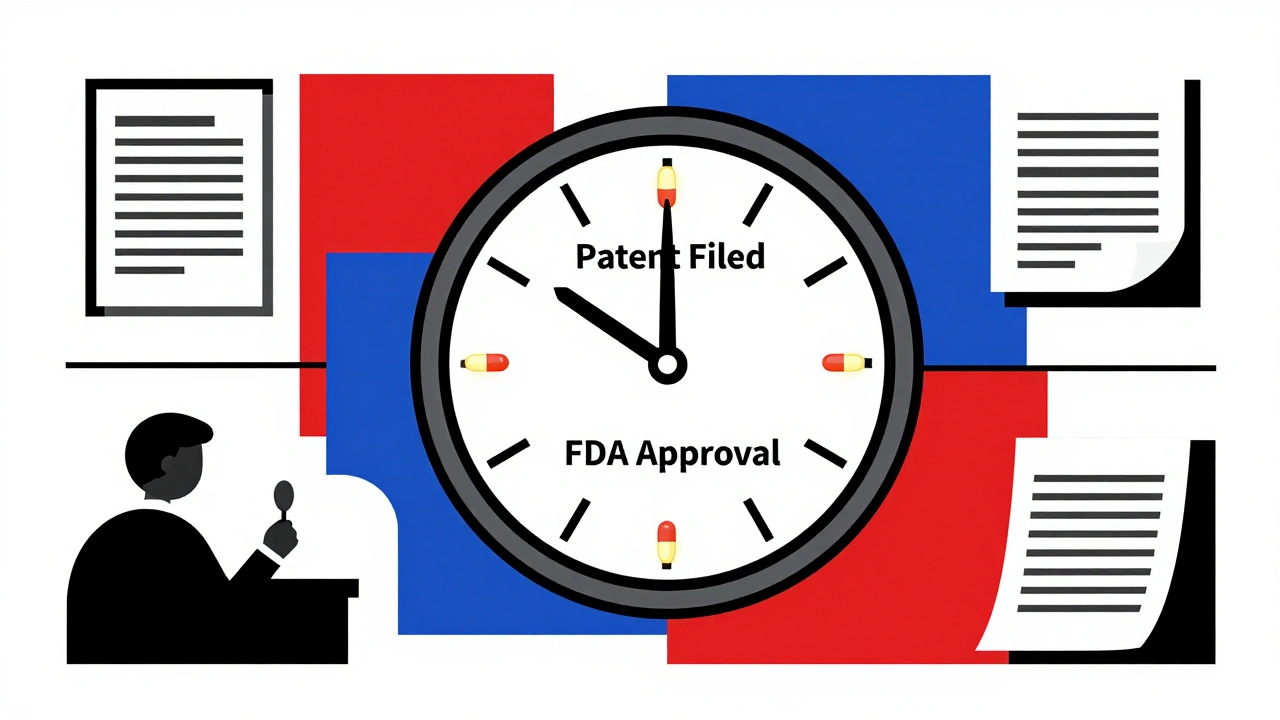

The 20-year patent term starts the day the drug’s inventor files the patent application. That’s usually years before the drug even enters human testing. Most drugs take 8 to 12 years to go from lab to pharmacy shelf. That’s because they need to pass multiple phases of clinical trials, get reviewed by the FDA, and meet safety and manufacturing standards.

By the time a drug finally gets approved, half the patent clock has already run out. So if a company files a patent in 2010 and gets FDA approval in 2020, they only have 10 years left before generics can enter. That’s not enough time to recover the $2.6 billion it typically costs to develop one new drug. That’s why effective patent life is so much shorter than the nominal 20 years.

The Hatch-Waxman Act: A Compromise That Changed Everything

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act-better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Its goal was simple: balance innovation with affordability. It gave drugmakers a way to get back some of the time lost during FDA review, while also making it easier for generics to enter the market.

Under Hatch-Waxman, companies can apply for a Patent Term Extension (PTE). This can add up to five years to the patent’s life. But there’s a hard cap: the total exclusivity time from FDA approval can’t exceed 14 years. So even if a drug took 10 years to get approved, the maximum patent extension is only 4 years (14 minus 10). If it took 12 years to get approved, the extension is just 2 years.

This system was designed for the average drug. But over time, companies found ways to stretch it further.

Secondary Patents: The Hidden Game of ‘Evergreening’

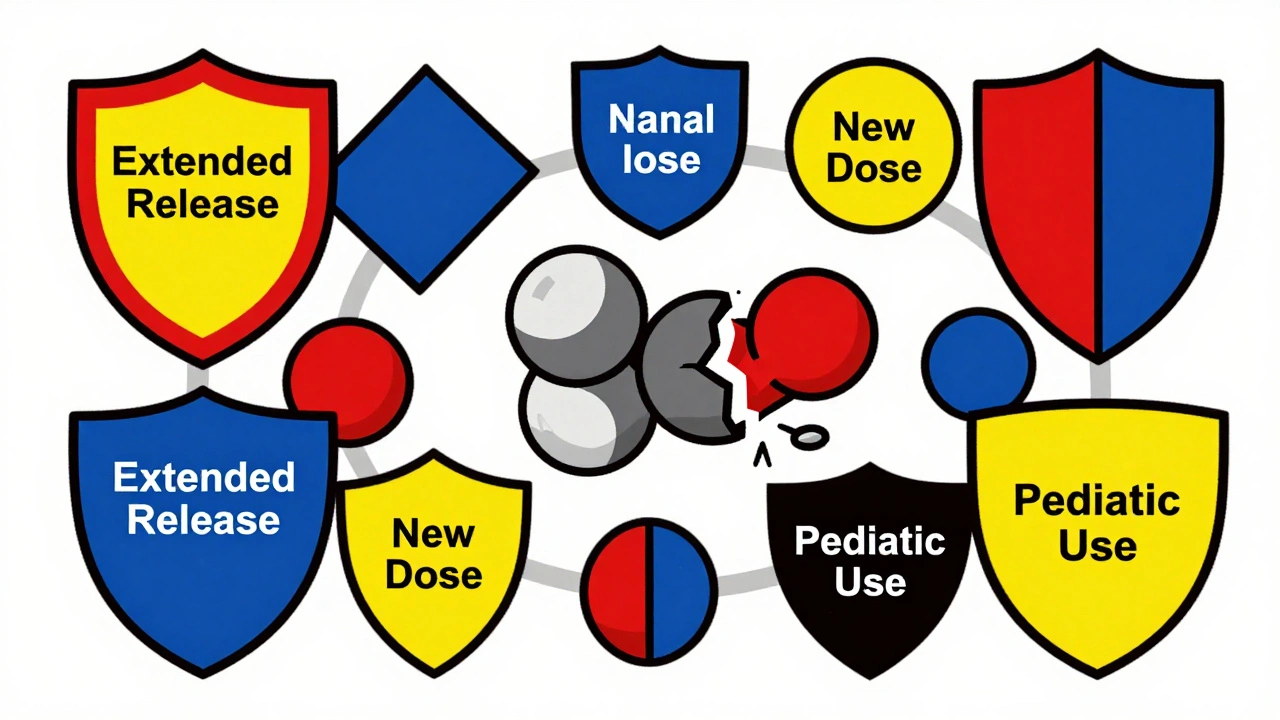

Once a drug is approved, companies don’t stop filing patents. They file new ones-for new doses, new delivery methods (like extended-release pills), new combinations with other drugs, or even for different patient groups.

These are called secondary patents. They’re not about the active ingredient itself. They’re about how it’s used or delivered. A blockbuster drug might have 20 to 30 of these patents. The R Street Institute found that high-selling drugs are 37% more likely to get these post-approval patents than lower-revenue ones.

This practice is known as ‘evergreening.’ It’s legal, but it’s not what Hatch-Waxman intended. These patents can delay generic entry by years-even after the original patent expires. In fact, 91% of drugs that got patent extensions still held off generics beyond the extension’s end, thanks to these secondary patents.

Regulatory Exclusivity: A Separate Layer of Protection

Patents aren’t the only thing protecting a drug. The FDA also gives out regulatory exclusivities-time periods during which it won’t approve a generic version, even if the patent has expired.

- New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity: 5 years of protection for a completely new active ingredient.

- New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity: 3 years for new uses or formulations of existing drugs.

- Orphan Drug Exclusivity: 7 years for drugs treating rare diseases (under 200,000 patients in the U.S.).

- Pediatric Exclusivity: An extra 6 months added to any existing patent or exclusivity period if the company studies the drug in children.

These exclusivities stack on top of patents. So a drug might have 5 years of NCE exclusivity, then 3 more years of clinical exclusivity, and still have 2 years left on a patent. That’s 10 years of legal protection-without a single patent being enforced.

How Generic Companies Break In-and How Brand Companies Fight Back

When a generic company wants to launch, they file an application with the FDA and send a notice to the brand company. If the brand company sues within 45 days, the FDA can’t approve the generic for 30 months. This is called the 30-month stay.

Many brand companies use this delay strategically. Even if their patent is weak, they sue anyway. The 30-month clock gives them time to file more patents, negotiate deals with generics, or launch their own ‘authorized generic’ to steal market share.

Meanwhile, the FDA keeps all patents and exclusivities listed in the Orange Book. It’s a public database, but it’s confusing. Generic manufacturers have to sort through dozens of patents to figure out which ones are real threats-and which are just noise.

Global Differences: It’s Not Just the U.S.

The U.S. isn’t the only country with this problem. Canada offers a Certificate of Supplementary Protection (CSP), giving up to 2 years of extra protection after patent expiry. Japan allows up to 5 years of patent term extension, similar to the U.S.

But in the European Union, the rules are tighter. Supplementary Protection Certificates (SPCs) are granted, but they’re harder to get and shorter in duration. Some countries don’t allow evergreening at all. That’s why many drugmakers file patents in the U.S. first-it’s the most lucrative market, and the rules are the most flexible.

The Real Cost: Billions at Stake

When a drug loses exclusivity, prices drop fast. Within a year, generics can cut the brand drug’s price by 80% to 90%. For a top-selling drug making $1 billion a year, that’s a $900 million revenue cliff.

That’s why companies spend millions on lifecycle management. They tweak the formula, change the packaging, add a new indication, or even shift the drug from prescription to over-the-counter. Every move is designed to keep patients on the brand-and keep revenue flowing.

By 2025, over $250 billion in global drug sales are expected to face patent expirations. For big pharma, it’s not just about losing money-it’s about losing entire business lines.

What’s Next? More Scrutiny, More Complexity

Regulators and lawmakers are starting to push back. Courts are questioning whether some secondary patents are valid. The FDA is under pressure to be more aggressive in rejecting patents that don’t add real therapeutic value.

At the same time, companies are getting smarter. They’re filing patents earlier, using data from clinical trials to support new claims, and partnering with generic makers to control the transition.

For patients and insurers, the result is a system that’s harder to understand but more expensive than it needs to be. For drugmakers, it’s a race against time-one they’re determined to win, even if the rules were never meant to last this long.

Why is effective patent life shorter than 20 years?

The 20-year patent clock starts when the drug is first patented, which is often 8 to 12 years before the FDA approves it for sale. That leaves only 8 to 12 years of actual market exclusivity. Even with patent term extensions, the total time from FDA approval is capped at 14 years.

What is the Hatch-Waxman Act?

The Hatch-Waxman Act of 1984 created a balance between brand-name drug companies and generic manufacturers. It allows brand companies to extend their patent term by up to 5 years to make up for time lost during FDA review, while letting generics enter the market faster by simplifying their approval process.

Can a drug have more than one type of exclusivity?

Yes. A drug can have both patent protection and regulatory exclusivity at the same time. For example, a new chemical entity gets 5 years of exclusivity from the FDA, and if it also has a patent, that patent can be extended. Pediatric exclusivity can add 6 months on top of both.

What are secondary patents and why do they matter?

Secondary patents cover new uses, formulations, or delivery methods of an existing drug-not the original active ingredient. They’re used to delay generic competition, a practice called ‘evergreening.’ A single drug can have 20 to 30 secondary patents, making it hard for generics to enter even after the main patent expires.

How long do generic drugs wait to enter the market?

It depends. If there are no patents or exclusivities left, generics can enter immediately after FDA approval. But if the brand company files a lawsuit, the FDA must wait 30 months before approving the generic-even if the patent is weak. Many generics wait years due to this legal delay.

Do all countries handle drug patents the same way?

No. The U.S. allows up to 5 years of patent extension and has the most aggressive use of secondary patents. Canada offers up to 2 years of supplementary protection. The EU has stricter rules and shorter extensions. Japan allows up to 5 years of extension, similar to the U.S., but with tighter review.

Why do drug prices drop so much after generics arrive?

Generics are cheaper because they don’t need to repeat expensive clinical trials. They prove they’re the same as the brand drug. With multiple generic makers competing, prices fall rapidly-often by 80% to 90% in the first year. The brand drug loses most of its market share and revenue.

Conor Forde

December 1, 2025 AT 19:25So let me get this straight - we pay $2.6B to make a pill, then get 10 years to make back our cash, and the rest is just legal jenga with patents? 🤯 Pharma’s playing 4D chess while the rest of us are stuck trying to figure out why our insulin costs more than our rent.

Matt Dean

December 3, 2025 AT 02:51Let’s be real - this isn’t about innovation. It’s about corporate greed wrapped in a lab coat. If you can’t make a profit in 10 years, you shouldn’t be in pharma. You should be flipping burgers. The system is rigged, and the public is the sucker.

Michelle Smyth

December 3, 2025 AT 23:28Oh wow, another ‘pharma is evil’ think piece. Have you considered that without these mechanisms, no one would risk developing drugs for rare diseases? The ‘evergreening’ you sneer at? That’s how we got life-saving pediatric formulations. Your outrage is performative, not principled.

patrick sui

December 5, 2025 AT 18:09Interesting breakdown - but let’s not forget the FDA’s role here. The agency’s review process is notoriously slow, and it’s not just bureaucracy - it’s liability avoidance. If they approve a drug too fast and someone dies, their career is over. So they drag their feet. Pharma’s gaming the system? Sure. But the system was built to be gamed.

Also, 30-month stays? That’s not a legal tool - it’s a corporate weapon. And it’s legal. 😒

Walker Alvey

December 5, 2025 AT 19:00Wow. A 12-year review process? That’s not a regulatory hurdle - that’s a taxpayer-funded vacation for Big Pharma. They get 20 years of monopoly, then whine about not having enough time. Go build a bridge, then charge people tolls to cross it. Same thing.

Declan O Reilly

December 6, 2025 AT 00:59It’s funny how we treat medicine like a commodity instead of a human right. We’ve turned healing into a spreadsheet. The 20-year patent was never meant to be a profit guarantee - it was meant to incentivize discovery. But now? It’s just a license to extract. We’re not protecting innovation - we’re protecting greed.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘authorized generics.’ That’s not competition. That’s a corporate ambush. You’re not undercutting your rival - you’re becoming your rival.

At what point do we say: ‘enough’? When the CEO buys his third island?

Declan Flynn Fitness

December 7, 2025 AT 20:26Big Pharma is just playing the system - and honestly? Good for them. 😎 If you’re smart enough to find loopholes in a 40-year-old law, you deserve the profit. The problem isn’t the companies - it’s that we let them write the rules.

Also, generics? They’re great. But they don’t pay for R&D. Someone’s gotta foot the bill. And right now? It’s us - through taxes, insurance, and out-of-pocket hell.

Wanna fix it? Don’t hate the players. Change the game.

Lucinda Bresnehan

December 8, 2025 AT 12:20I’m from Nigeria and I’ve seen what happens when drugs are too expensive - people die waiting. The U.S. system is broken, but I also get why it’s like this. Innovation costs money. The problem is the balance. We need a global standard - not just for patents, but for access. Everyone deserves medicine, not just those who can afford it.

Maybe we should start by letting low-income countries import generics without lawsuits. That’s not theft. That’s survival.

Nnaemeka Kingsley

December 9, 2025 AT 18:40so pharma gets 20 years but only 10 to make money? damn. i thought they had 20 years of monopoly. so they just make more patents on the same pill? that’s wild. like putting a new sticker on a soda can and charging more. 😅

Shannon Gabrielle

December 9, 2025 AT 23:22Oh sweet Jesus. Another ‘pharma’s evil’ post. Let me guess - you also think Amazon should be banned because it makes too much money? You want the government to set drug prices? Fine. Then tell me why your iPhone costs $1,000 and your insulin costs $500? Oh wait - because one’s tech and one’s medicine. So one’s a luxury and one’s a right? How convenient.

Here’s the truth: innovation doesn’t happen in a vacuum. It happens because people get rich doing it. If you want cheap drugs, stop pretending the system is unfair and start paying more taxes to fund public R&D. But no - you’d rather scream about ‘corporate greed’ while still buying the brand-name version.

ANN JACOBS

December 11, 2025 AT 15:20While the structural inefficiencies in pharmaceutical patent law are indeed troubling, one must not overlook the broader socio-economic implications of this regulatory framework. The current paradigm, though imperfect, incentivizes capital-intensive research and development in an industry where failure rates exceed 90% during clinical trials. The economic model underpinning drug innovation requires a sufficient return on investment to justify the astronomical costs associated with safety validation, manufacturing scalability, and post-marketing surveillance. Without the mechanisms of patent term extension and regulatory exclusivity, the pipeline for novel therapeutics - particularly for oncology, neurodegenerative, and rare disease indications - would collapse entirely. The alternative is not ‘fair pricing’ but ‘no pricing,’ which translates to no drugs.

Furthermore, the proliferation of secondary patents, while ethically contentious, reflects the natural evolution of therapeutic delivery systems. Extended-release formulations, for instance, improve patient adherence and reduce adverse events - clinical benefits that are not trivial. To dismiss them as mere ‘evergreening’ is to misunderstand the science and the patient experience.

What is required is not the dismantling of the system, but its refinement: enhanced transparency in the Orange Book, expedited FDA review for truly innovative compounds, and tiered pricing models that ensure global access without undermining domestic innovation. The challenge is not to punish success, but to align incentives with public health outcomes.

Adrian Barnes

December 12, 2025 AT 04:20You’re all missing the real scandal. The FDA is a regulatory capture nightmare. The same consultants who design the approval protocols for pharma companies are the same ones who sit on FDA advisory boards. The 30-month stay? It’s not a legal tool - it’s a bribe. The entire system is designed to enrich shareholders while the public pays the price in suffering, bankruptcy, and early death. This isn’t capitalism. It’s feudalism with a patent lawyer.

Conor Forde

December 12, 2025 AT 17:48And now the author’s gonna reply with a 5000-word essay on ‘market equilibrium.’ 😭