When a brand-name drug loses its patent, everything changes. For the company that spent years and billions developing it, the moment generic versions hit the market isn’t just a business setback-it’s a financial earthquake. Revenue doesn’t slowly decline. It crashes. In many cases, within a year, brand manufacturers see 80 to 90% of their sales vanish overnight. This isn’t hypothetical. It’s happening right now with drugs like Humira, which lost exclusivity in 2023 and saw its global sales plunge from over $20 billion to under $4 billion in less than 12 months. The reason? Generics.

Generic drugs aren’t knockoffs. They’re exact copies. Same active ingredient. Same dosage. Same way of taking it. Same safety profile. The FDA requires them to be therapeutically equivalent. But here’s the kicker: they cost 80 to 85% less. That’s not a marketing claim. It’s data from the FDA’s own analysis of thousands of drugs approved between 2018 and 2020. When a generic enters the market, the price doesn’t just drop-it collapses. And it keeps falling. With three competitors, prices fall about 20% in the first three years. With five or more, they can drop by more than 70% from the original brand price.

Why Generics Are a $330 Billion Savings Machine

Generics aren’t just cheaper-they’re the biggest reason prescription drug spending in the U.S. hasn’t exploded even faster. In 2023, generics made up 90% of all prescriptions filled. Yet they accounted for only about 20% of total spending. That gap? That’s where the savings live. The Congressional Budget Office estimated generics saved the U.S. system $253 billion in 2014 alone. By 2023, that number had climbed to $330 billion annually. That’s more than the entire annual budget of the CDC. It’s more than what the U.S. spends on public school lunches. These aren’t small numbers. They’re systemic.

For patients, this means a monthly diabetes pill that cost $400 as a brand can now cost $15 as a generic. An asthma inhaler that once set people back $300 is now $25. That’s not charity. It’s competition. And it’s working-mostly.

The Brand Manufacturer’s Dilemma

For brand manufacturers, the patent expiration date is like a ticking bomb. They know it’s coming. They plan for it. But no amount of forecasting prepares them for the scale of the drop. Their entire business model is built on monopoly pricing. While they hold the patent, they can charge what they want. No competition. No pressure. Just high margins. Once that’s gone, they’re stuck. Some try to fight it. Others adapt.

One common tactic? Pay-for-delay. It sounds shady because it is. A brand manufacturer pays a generic company to delay launching its version. In exchange, the generic company gets a chunk of cash-sometimes hundreds of millions-and avoids the risk of a price war. The Blue Cross Blue Shield Association estimates these deals cost patients $3 billion a year in extra out-of-pocket costs. The Congressional Budget Office says banning them could save $45 billion over ten years. Yet they still happen. Why? Because the alternative-watching your flagship drug’s revenue vanish-is worse.

Another trick? Product hopping. A company slightly changes its drug-switches from a pill to a liquid, adds a time-release coating, or changes the delivery device-and then files a new patent. This resets the clock. Patients get a new version they’re told is "better," even though the active ingredient hasn’t changed. The CBO estimates ending this practice would save $1.1 billion over ten years. But it’s legal. And profitable.

Who Really Benefits? (Hint: Not Always the Patient)

Here’s where things get messy. You’d think lower drug prices mean lower costs for everyone. But that’s not always true. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs)-the middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drugmakers-have become powerful players. They negotiate rebates, set formularies, and control which drugs get covered. And they’re not always passing savings along.

The Schaeffer Center at USC found that patients often pay 13 to 20% more than they should for generics because of opaque PBM pricing. How? PBMs take a cut based on the list price, not the actual cost. So if a generic drug’s wholesale price drops from $20 to $10, but the PBM still charges $18, the patient pays $18. The pharmacy loses money. The PBM pockets the difference. And the patient? Still paying too much.

Pharmacists on Reddit and industry forums report being paid less than what they paid for the drug. Some pharmacies are losing money on every generic prescription they fill. Yet they’re forced to keep filling them because patients need the medication. It’s a broken system.

How Brand Manufacturers Are Adapting

Some brands are fighting. Others are changing. Novartis, for example, spun off its generics division, Sandoz, into a separate company in 2022. Why? To create a clear divide: one arm focused on high-margin innovation, the other on low-margin volume. It’s a smart move. It lets investors see the risks and rewards separately.

Other companies are developing authorized generics-versions of their own drug sold under a generic label. This lets them keep some revenue even after the patent expires. Pfizer, for instance, quietly launched its own generic version of Lipitor after the patent lapsed. It didn’t stop the price crash, but it kept a slice of the pie.

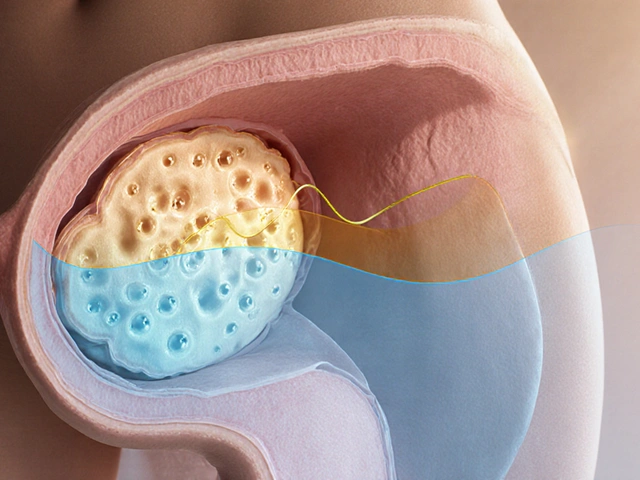

Some are shifting focus. Instead of chasing blockbuster drugs with short patent lives, they’re investing in complex therapies-gene therapies, cell therapies, biologics-that are harder to copy. These drugs don’t face generic competition for years, sometimes decades. But they cost $500,000 or more per patient. So while generics save money on pills, they’re not helping with the next wave of expensive treatments.

The Coming Storm: 0 Billion at Risk

By 2028, analysts at Evaluate Pharma predict $400 billion in brand drug revenue will be exposed to generic competition. That’s more than the entire U.S. healthcare budget for Medicaid. Drugs like Humira, Enbrel, and Keytruda are just the beginning. Dozens of blockbuster drugs are set to lose patent protection in the next five years. For companies that rely on these drugs for half their revenue, the next decade will be brutal.

Manufacturers are scrambling. Some are buying up generic companies. Others are investing in manufacturing to cut costs. A few are trying to move production overseas, where labor and regulation are cheaper. But there’s a trade-off. As prices drop, profit margins shrink. And when margins get too thin, companies cut corners. That’s when shortages happen. The FDA has warned that the pressure to make generics cheaper is leading to supply disruptions. One drug might be out of stock for months because the last manufacturer left the market.

What’s Next?

Legislation is starting to catch up. Bipartisan bills in Congress are pushing to ban pay-for-delay deals. The FDA’s GDUFA program, reauthorized in 2022 with $1.1 billion in fees from industry, is speeding up generic approvals. More approvals mean more competition. More competition means lower prices.

But the system is still rigged. PBMs still control pricing. Patents are still being stretched. Patients still pay more than they should. And brand manufacturers? They’re still trying to hold on to the old model while the world moves on.

Generics aren’t the enemy. They’re the correction. They’re what happens when a market finally works. The problem isn’t generics. It’s the structures around them-patents, middlemen, pricing games-that keep the system from delivering its full promise.

For patients, the future should be simple: a cheap, reliable, available generic for every drug. For manufacturers, it’s harder. They’ll need to stop treating drugs like luxury goods and start treating them like essentials. The market is telling them what to do. The question is-will they listen?

Why do generic drugs cost so much less than brand-name drugs?

Generic drugs cost less because they don’t have to repeat the expensive clinical trials that brand-name drugs go through. The FDA requires generics to prove they’re bioequivalent-meaning they work the same way-but doesn’t require new safety or efficacy studies. That cuts development costs by 80% or more. Plus, once multiple companies start making the same drug, competition drives prices down. Brand manufacturers, on the other hand, recoup billions in R&D and marketing costs during their patent monopoly.

Do generic drugs work as well as brand-name drugs?

Yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name version. They must also meet the same strict manufacturing standards. Studies show they work just as effectively. In fact, the same companies often make both the brand and generic versions-just under different labels. The difference is price, not quality.

What is the "patent cliff" and why does it matter?

The "patent cliff" is the moment a brand-name drug loses its patent protection and generic versions can legally enter the market. For pharmaceutical companies, this is a financial cliff. Revenue typically drops 80-90% within the first year. Companies like Pfizer and AbbVie have seen stock prices plunge after major patent expirations. It forces them to either innovate faster, diversify, or risk financial instability.

Why are some generic drugs still expensive?

Some generics stay expensive because there’s little competition. If only one or two companies make a drug, they can keep prices high. This often happens with complex generics-like injectables or inhalers-where manufacturing is harder and fewer companies can produce them. Also, opaque pricing by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) can inflate what patients pay, even when the wholesale price is low.

Can brand manufacturers legally delay generic entry?

Yes, through legal loopholes. "Pay-for-delay" agreements, where a brand company pays a generic maker to delay launch, are still allowed in the U.S., though they’re being challenged in court and Congress. "Product hopping"-making minor changes to a drug to reset patent clocks-is another tactic. Both are legal but widely criticized for delaying competition and keeping prices high.

Scott Conner

February 8, 2026 AT 16:32Lyle Whyatt

February 10, 2026 AT 12:13Tatiana Barbosa

February 11, 2026 AT 23:02Ryan Vargas

February 12, 2026 AT 09:36Simon Critchley

February 12, 2026 AT 17:54John McDonald

February 14, 2026 AT 09:09Chelsea Cook

February 15, 2026 AT 14:04John Sonnenberg

February 16, 2026 AT 21:47Joshua Smith

February 17, 2026 AT 11:50