It’s easy to assume that if you break out in hives or feel sick after eating or taking something, it’s an allergy. But not all reactions are created equal. Food allergies and medication allergies may look similar on the surface-rashes, swelling, trouble breathing-but they’re fundamentally different in how they happen, when they show up, and how they’re diagnosed. Mistaking one for the other can lead to unnecessary dietary restrictions, dangerous avoidance of life-saving drugs, or worse, missing a real threat that could kill you.

How Your Body Reacts: IgE vs. Other Pathways

Most food allergies are triggered by immunoglobulin E (IgE), a type of antibody that reacts fast. When you eat something like peanuts, shellfish, or milk, your immune system sees it as an invader and releases histamine and other chemicals. That’s why symptoms like itching in the mouth, hives, vomiting, or anaphylaxis happen within minutes-sometimes as fast as 5 to 20 minutes after eating. About 90% of serious food reactions follow this pattern.

Medication allergies can also be IgE-mediated, but they’re more complex. About 80% of immediate drug reactions (like penicillin rashes or anaphylaxis) work the same way. But the other 20%? Those are delayed. They’re driven by T-cells, not IgE. That means symptoms like a widespread rash, fever, or blistering skin (like Stevens-Johnson syndrome) might not show up until days or even weeks after you took the medicine. This delay makes it harder to connect the reaction to the drug, especially if you’re sick with a virus at the same time.

Timing Is Everything

One of the clearest ways to tell them apart is by timing. If you ate a slice of pizza and your lips swelled up 15 minutes later? That’s almost certainly a food allergy. If you took amoxicillin for a sore throat and got a rash three days later? That’s likely a medication reaction-but not necessarily a true allergy.

Here’s the breakdown:

- Food allergies: 95% of reactions happen within 2 hours. Median time? 20 minutes.

- Medication allergies: Immediate reactions (within 1 hour) happen in 85% of IgE cases. Delayed reactions (48-72 hours or longer) are common with antibiotics, anticonvulsants, or chemotherapy drugs.

That’s why doctors ask: When did you start feeling sick after taking or eating it? A rash that appears a week after starting a new pill is rarely a true IgE allergy. It’s more likely a non-allergic drug reaction or even a virus-related rash mistaken for an allergy.

Symptoms: Where the Reactions Show Up

Both can cause hives, swelling, or breathing trouble. But there are clues.

Food allergies often start in the mouth and gut. About 70% of people feel itching or tingling in their lips, tongue, or throat right after eating the trigger food. Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea are common too-especially in kids. In fact, 55% of pediatric food allergy reactions include vomiting.

Medication allergies? They’re more likely to hit the skin broadly. A flat, red, itchy rash (maculopapular) is the #1 sign in delayed reactions. Fever, swollen lymph nodes, or joint pain are also common with drug reactions like DRESS syndrome. Respiratory symptoms like wheezing happen in both, but they’re more frequent in food allergies during anaphylaxis.

Here’s a key point: Food allergies rarely cause fever. If you get a fever after eating something, it’s probably not an allergy-it’s an infection, or something else.

Diagnosis: Testing Is the Only Way to Know

Self-diagnosis is risky. Many people think they’re allergic to penicillin because they got a rash as a kid. But studies show up to 90% of those people aren’t actually allergic. Same with food: someone might say they’re allergic to eggs because they got a stomachache once. But that could be intolerance, not allergy.

For food allergies, the gold standard is a combination of skin prick tests and blood tests for IgE antibodies. But even those aren’t perfect. The real test? An oral food challenge-eating the food under medical supervision. It’s the only way to confirm a diagnosis with 95% accuracy. And yes, it’s scary. But it’s safer than avoiding foods you don’t actually need to.

For medications, it’s trickier. Penicillin testing is well-established: skin tests followed by a small oral dose under watch. If you pass, you’re not allergic. For other drugs, like NSAIDs or sulfa drugs, there’s no reliable blood or skin test. Doctors may do a controlled drug provocation test-giving a tiny amount of the drug and watching closely. It’s not done lightly, but it’s the only way to rule out a false allergy.

And here’s the kicker: component-resolved diagnostics (CRD) can now tell you if you’re allergic to peanut protein (Ara h 2) or just reacting to pollen cross-reactivity (Ara h 8). That’s huge for people who thought they were allergic to peanuts but can actually eat them safely.

Why Getting It Right Matters

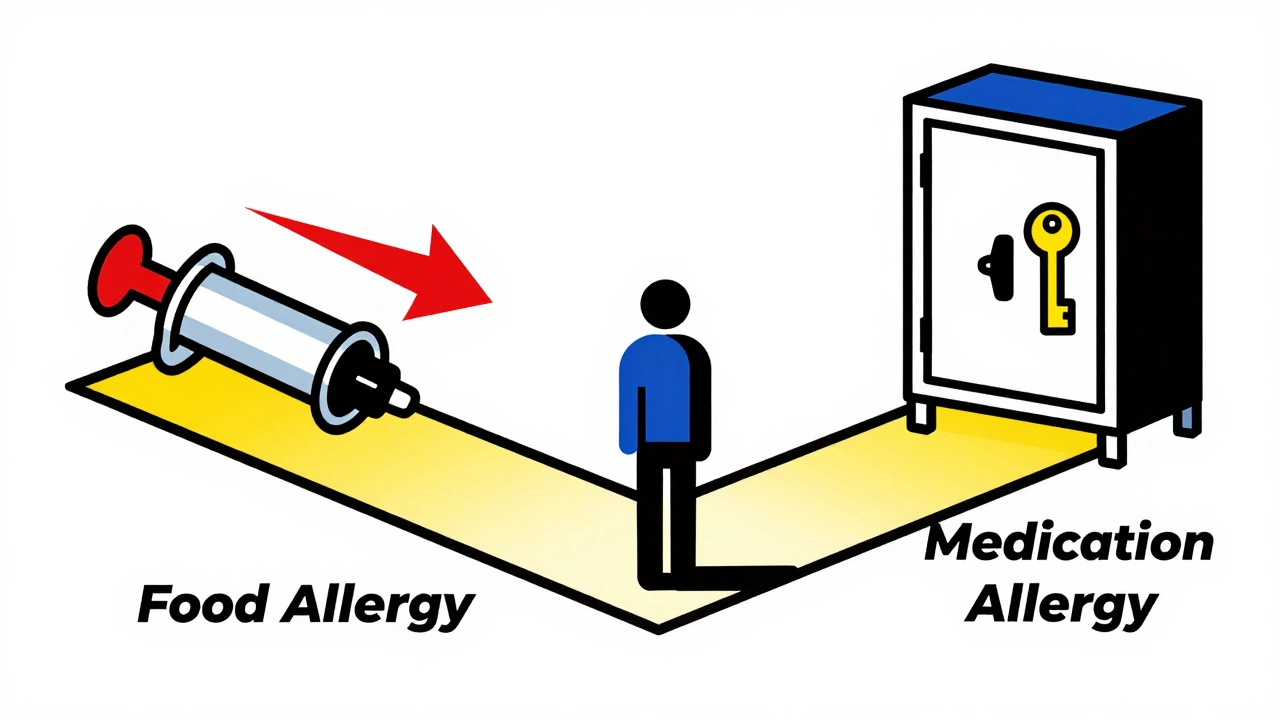

False food allergy labels can lead to nutritional gaps, especially in kids. Avoiding dairy because you think you’re allergic? You might miss out on calcium and vitamin D. Avoiding eggs? You lose a key protein source.

But false medication allergies? They’re costlier-and deadlier. People labeled as penicillin-allergic are often given broader-spectrum antibiotics like vancomycin or fluoroquinolones. These drugs are 30% more expensive and increase the risk of deadly infections like C. diff by 25%. A 2022 JAMA study found that 15-20% of antibiotic avoidance is based on misdiagnosed allergies.

And here’s the scary part: 150-200 Americans die every year from food-induced anaphylaxis, mostly because they didn’t recognize the symptoms early or didn’t have epinephrine ready. Meanwhile, up to 40% of hospital admissions involve drug reactions, and many are preventable with better diagnosis.

What You Can Do Right Now

If you think you have an allergy, don’t guess. Track everything:

- For food: Write down what you ate, when, how it was prepared, and exactly when symptoms started. Did the reaction happen every time? Or just once?

- For medication: Note the drug name, dose, time taken, and when symptoms appeared. Did you take it with food? Were you sick with a virus? Many rashes from amoxicillin in kids with mono are mislabeled as allergies.

Take this info to an allergist-not your GP. They know how to interpret patterns. Ask about testing. If you’ve been told you’re allergic to penicillin, ask if you can get tested. Most people who think they are allergic aren’t. And if you’ve been avoiding milk or eggs since childhood, ask if you’re still allergic. About 80% of kids outgrow milk and egg allergies by age 5.

Don’t let a label from 10 years ago limit your health today.

Common Misconceptions

Here are the myths that trip people up:

- Myth: If I got sick after eating something once, I’m allergic. Truth: One reaction doesn’t mean allergy. True allergies are reproducible. You react every time.

- Myth: All rashes from antibiotics are allergies. Truth: Most are not. Viral rashes, especially in kids on amoxicillin, are common and harmless.

- Myth: If I reacted to one drug, I’m allergic to all in that class. Truth: Not true. You might react to amoxicillin but tolerate cephalexin just fine.

- Myth: Food intolerances are just mild allergies. Truth: They’re completely different. Lactose intolerance is a digestion issue, not an immune reaction.

One real case: A 34-year-old woman avoided all NSAIDs for a decade because she thought she was allergic to aspirin. Turns out, she was reacting to the lactose in the pill filler-not the aspirin. Once she switched to a lactose-free version, she could take NSAIDs safely.

Another: A mother kept blaming antibiotics for her son’s hives. After a detailed food diary and testing, it turned out to be dairy. He’d been avoiding penicillin unnecessarily for two years.

What’s Changing Now

New tools are making diagnosis faster and more accurate. In 2023, the FDA approved a blood test (ImmunoCAP® Penicillin) that can rule out penicillin allergy with 98% accuracy. For food allergies, CRD testing now separates true peanut allergies from harmless cross-reactions.

Hospitals are also starting to implement “antibiotic allergy delabeling” programs. These involve reviewing patient records, testing those with old allergy labels, and updating charts. One hospital cut unnecessary broad-spectrum antibiotic use by 25% in 18 months.

And digital tools are emerging-apps that help track food intake and symptoms in real time, making it easier to spot patterns.

Final Thought

You don’t need to live in fear of every new food or pill. But you do need to know the difference between a real allergy and a coincidence. The right diagnosis doesn’t just prevent a rash-it can save your life, spare you from dangerous drugs, and help you eat without anxiety. If you’ve ever been told you have an allergy, ask: Was it confirmed? Or just assumed? The answer could change everything.

Can you outgrow a food allergy?

Yes, many children outgrow allergies to milk, eggs, wheat, and soy-up to 80% by age 5. Peanut and tree nut allergies are less likely to be outgrown, but about 20% of kids do. Testing every few years under medical supervision can determine if the allergy is still active.

Is a penicillin allergy real if I only had a rash as a child?

Probably not. Most rashes from penicillin in children are not true allergies-they’re often viral rashes that coincided with the drug. Up to 90% of people who report a penicillin allergy test negative when properly evaluated. Skin testing and oral challenge can confirm whether you’re truly allergic.

Can medication allergies develop later in life?

Absolutely. While food allergies usually start in childhood, medication allergies can develop at any age. The average age for a new drug allergy is 42. You might take amoxicillin for years without issue, then suddenly react after a viral infection. That’s why doctors don’t assume past tolerance means future safety.

What’s the difference between an allergy and an intolerance?

An allergy involves the immune system and can be life-threatening. An intolerance doesn’t involve immunity-it’s usually a digestive issue. Lactose intolerance causes bloating or diarrhea because you lack the enzyme to break down milk sugar. A milk allergy triggers hives, vomiting, or anaphylaxis because your immune system attacks milk proteins.

Should I carry an epinephrine auto-injector if I have a food allergy?

If you’ve had a severe reaction before-like trouble breathing, swelling of the throat, or a drop in blood pressure-yes. Even if your last reaction was mild, your next one could be worse. Epinephrine is the only treatment that stops anaphylaxis. Don’t wait to use it. Call 911 after injecting, even if you feel better.

Can I be allergic to both food and medication?

Yes. Having one type of allergy doesn’t protect you from another. Many people with food allergies also have drug allergies, and vice versa. The key is to track each reaction separately and get proper testing for each suspected trigger. Don’t assume one diagnosis explains all your symptoms.

Why do some people get rashes from amoxicillin but not other antibiotics?

Amoxicillin is a common trigger for non-allergic rashes, especially in kids with viral infections like Epstein-Barr or roseola. The rash is usually flat, pink, and doesn’t itch much. It’s not an IgE reaction and doesn’t mean you’re allergic to penicillin or other beta-lactams. But because it looks like an allergy, many are mislabeled. Testing later can clear that up.

Are food allergy tests always accurate?

Skin and blood tests can show sensitization, but not always true allergy. A positive test means your body has made antibodies, but you might still eat the food without reacting. Only an oral food challenge-eating the food under supervision-can confirm a true allergy with high accuracy.

Iris Carmen

December 10, 2025 AT 02:39Rich Paul

December 11, 2025 AT 09:32Ruth Witte

December 12, 2025 AT 10:51Ronald Ezamaru

December 14, 2025 AT 09:06Lola Bchoudi

December 15, 2025 AT 05:21Delaine Kiara

December 16, 2025 AT 09:24Raja Herbal

December 17, 2025 AT 19:15Stacy Tolbert

December 19, 2025 AT 13:04Noah Raines

December 20, 2025 AT 00:00Katherine Rodgers

December 20, 2025 AT 21:04Shubham Mathur

December 21, 2025 AT 06:17Taya Rtichsheva

December 21, 2025 AT 22:51Michael Robinson

December 22, 2025 AT 17:20Darcie Streeter-Oxland

December 24, 2025 AT 02:35Haley P Law

December 25, 2025 AT 20:31