When a generic drug hits the market, regulators need to be sure it works just like the brand-name version. But traditional bioequivalence studies-where 24 to 48 healthy volunteers give multiple blood samples over hours-don’t always reflect what happens in real patients. What if the drug is meant for elderly people with kidney problems? Or children? Or those on five other medications? That’s where population pharmacokinetics comes in.

Why traditional bioequivalence falls short

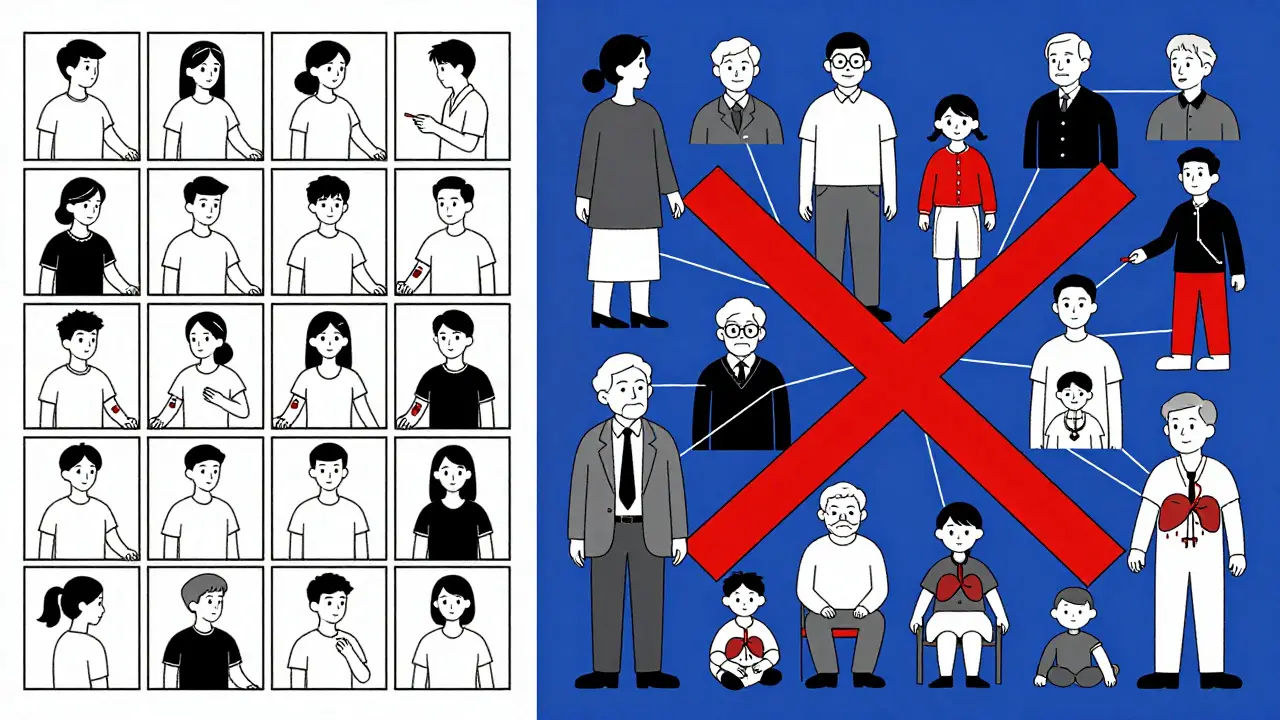

For decades, the gold standard for proving two drugs are equivalent was the crossover bioequivalence study. Healthy volunteers take both versions, blood is drawn every 15 to 30 minutes, and the area under the curve (AUC) and peak concentration (Cmax) are compared. If the 90% confidence interval for the ratio falls between 80% and 125%, the drugs are deemed equivalent. But here’s the problem: healthy young adults aren’t the people who actually take most of these drugs. A heart medication might be prescribed to a 78-year-old with diabetes and reduced kidney function. An epilepsy drug might be given to a 5-year-old who can’t swallow pills. A cancer drug might be used by someone with liver damage. Traditional studies don’t capture these realities. And in some cases, testing these populations directly is unethical or impossible. That’s where population pharmacokinetics (PopPK) changes the game. Instead of relying on a small, controlled group, PopPK uses sparse, real-world data from hundreds of patients-often collected during routine care. One patient gives one blood sample after a morning dose. Another gives two samples over two days. Another, with irregular dosing, gives three samples over a week. These aren’t perfect datasets. But when you put them all together with the right math, you get a powerful picture of how the drug behaves across a real population.How PopPK works: the math behind the magic

At its core, PopPK uses nonlinear mixed-effects modeling. Think of it as two layers of analysis. The first layer looks at each individual’s drug concentration over time. The second layer looks at how all those individuals differ from each other-and why. The model identifies what’s called between-subject variability (BSV). This is the natural variation in how people absorb, distribute, metabolize, and clear a drug. For some medications, BSV is low-maybe 15%. For others, like warfarin or phenytoin, it can be over 50%. PopPK quantifies this. It also measures residual unexplained variability (RUV), which captures random noise-like lab errors or timing mistakes in sample collection. Then it looks at covariates: things like weight, age, kidney function, liver enzymes, or whether the patient is taking another drug that affects metabolism. If a patient’s creatinine clearance drops below 40 mL/min, does their drug exposure spike by 40%? PopPK finds out. And if two formulations behave the same way across all those variables-same average exposure, same spread of variability-they’re equivalent. The FDA’s 2022 guidance made it official: PopPK data can replace traditional bioequivalence studies in certain cases. You don’t need 48 healthy volunteers if you have 60 patients with kidney impairment, each with two blood samples, and a model that shows their exposure is statistically identical between the two drugs.Regulatory acceptance: FDA, EMA, and global shifts

The FDA didn’t just nod at PopPK-they wrote a 78-page guide in 2022 spelling out exactly how to do it right. They say PopPK can eliminate the need for postmarketing studies, reduce trial costs, and speed up approvals. Between 2017 and 2021, about 70% of new drug applications included PopPK analyses to support dosing across populations. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has been more cautious but still accepts PopPK for equivalence, especially in special populations. Their 2014 guideline says PopPK can “account for variability in terms of patient characteristics.” That’s key. It’s not just about average exposure-it’s about whether the whole range of exposure is acceptable across different groups. Japan’s PMDA adopted similar standards in 2020. And biologics? Forget traditional bioequivalence. You can’t give a 70-kilogram antibody to 48 healthy people and call it a day. PopPK is the only practical way to prove biosimilar equivalence. But it’s not universal. Some EMA committees still prefer traditional data. And regulators in other regions may not have the expertise to evaluate complex models. A pharmacist in Sydney might see a generic drug approved in the U.S. using PopPK, only to find it’s not accepted locally-because the data wasn’t presented in a way their reviewers understood.

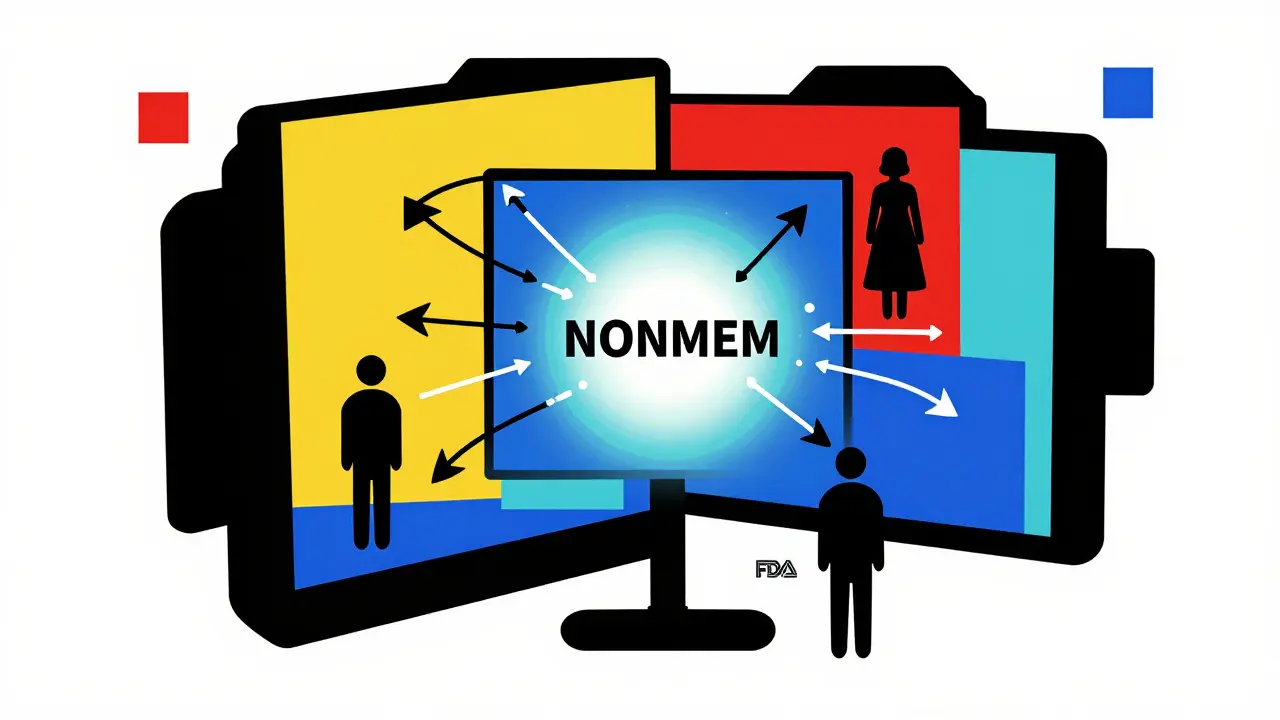

Tools of the trade: software and expertise

You can’t run PopPK in Excel. You need specialized software. NONMEM has been the industry standard since 1980. It’s old, clunky, and powerful. Monolix and Phoenix NLME are newer alternatives, but NONMEM still runs 85% of regulatory submissions, according to 2022 data. But software is only half the battle. The real challenge is expertise. It takes 18 to 24 months of focused training for a pharmacokineticist to become proficient-not just in running models, but in knowing how to design the study, choose the right covariates, avoid overfitting, and validate the model properly. And validation? That’s the biggest headache. A 2012 review called it “a lack of consensus regarding both terminology and the concept of validation itself.” Even today, 65% of pharmacometricians say model validation is their biggest obstacle. What does “validation” even mean? Does it mean the model predicts new data well? Does it mean it’s biologically plausible? Does it mean regulators accept it? There’s no single answer. That’s why early planning matters. If you wait until Phase 3 to think about PopPK, it’s too late. You need to design your clinical trial with sparse sampling in mind from Day 1. You need to collect data on weight, age, lab values, concomitant meds-everything that might affect drug levels. If you don’t, your model will be garbage, no matter how fancy the software.Where PopPK shines-and where it doesn’t

PopPK is perfect for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index. Think digoxin, cyclosporine, or warfarin. A 10% difference in exposure could mean toxicity or treatment failure. PopPK can show that two formulations have identical exposure profiles across the entire population-even if one group has low kidney function or high body weight. It’s also essential for pediatric and geriatric populations. You can’t ethically give a 6-month-old five blood draws. But if you have 80 infants on routine monitoring, each with one or two samples, PopPK can build a model that predicts exposure with high accuracy. But it’s not always the best tool. For drugs with extremely high variability-like some antiepileptics-traditional replicate crossover studies still give more precise estimates of within-subject variability. PopPK can’t always tell you if the same person will have wildly different levels on different days. That’s a different kind of problem. And for simple, well-behaved drugs with wide therapeutic windows? Sometimes, a traditional study is faster, cheaper, and easier to defend.

Real-world impact: cost, time, and patient access

The numbers speak for themselves. Companies like Merck and Pfizer report that using PopPK to prove equivalence has reduced the need for additional clinical trials by 25% to 40%. That’s not just money saved-it’s faster access to life-saving drugs. One case: a generic version of a critical antifungal drug for immunocompromised patients. Traditional bioequivalence studies would have required testing in patients with severe liver disease-high risk, low numbers. Instead, the company used PopPK data from 72 patients across multiple centers, each with 2-3 samples. The model showed no meaningful difference in exposure. The generic was approved in 14 months instead of 36. Machine learning is now being added to the mix. A January 2025 Nature paper showed how AI models can detect hidden, nonlinear relationships-like how a drug’s clearance changes only when a patient’s albumin level drops below 3.0 g/dL and they’re taking a specific antibiotic. These are the kinds of subtleties traditional models miss.What’s next? Standardization and global alignment

The biggest hurdle now isn’t the science-it’s the consistency. Different companies build models differently. Some include 10 covariates. Others only three. Some use parametric assumptions. Others go nonparametric. Regulators don’t always agree on what’s acceptable. That’s why groups like the IQ Consortium are working to standardize model qualification by late 2025. They want a common language: what counts as a valid model? What validation steps are mandatory? How much data is enough? The goal? Global harmonization. Imagine a generic drug approved in the U.S., EU, Japan, and Australia using the same PopPK data. That’s the future. And it’s not just possible-it’s inevitable.Final takeaway: data, not just numbers

Population pharmacokinetics isn’t about replacing traditional bioequivalence. It’s about expanding it. It’s about asking: Does this drug work the same way for everyone? Not just in a lab, but in the real world-with all its messiness, diversity, and complexity. The tools are here. The regulators are listening. The data is there. What’s missing is the mindset shift-from thinking about average patients to thinking about real ones. If you’re developing a drug for a population that’s not healthy, not young, and not simple-PopPK isn’t just an option. It’s the only way to prove you’re doing right by them.Can population pharmacokinetics replace traditional bioequivalence studies completely?

Not always. PopPK is accepted by the FDA and EMA for specific cases-especially when studying special populations like children, the elderly, or those with organ impairment, or for drugs with narrow therapeutic windows. But for highly variable drugs or when regulators demand direct comparison of within-subject variability, traditional crossover studies are still preferred. PopPK complements, rather than fully replaces, traditional methods.

How many patients are needed for a reliable PopPK analysis?

The FDA recommends at least 40 participants for robust parameter estimation. But the real number depends on the expected variability and the strength of the covariate effects. For example, if you’re studying a drug where weight strongly affects clearance, you might need fewer patients. If the effect is subtle, you may need 80 or more. The key isn’t just quantity-it’s the quality and spread of the data across different patient types.

What software is used for population pharmacokinetics modeling?

NONMEM is the industry standard and used in 85% of FDA submissions. Other tools include Monolix, Phoenix NLME, and R packages like nlme and saemix. While newer tools are more user-friendly, NONMEM remains dominant in regulatory submissions due to its long track record and validation history. Training in these tools typically takes 18-24 months to reach regulatory proficiency.

Why is model validation such a challenge in PopPK?

There’s no universal definition of what makes a PopPK model “valid.” Does it mean it predicts new data accurately? Is it biologically plausible? Does it match regulatory expectations? Different agencies and sponsors interpret validation differently. This lack of standardization leads to inconsistent reviews and frequent requests for additional data. Efforts by groups like the IQ Consortium aim to create common validation criteria by 2025.

Is PopPK used for biosimilars?

Yes, it’s essential. Traditional bioequivalence studies don’t work for large biologic molecules like monoclonal antibodies. Their size, complexity, and sensitivity to manufacturing changes make direct comparison impractical. PopPK, combined with immunogenicity and clinical outcome data, is the primary method used globally to demonstrate biosimilar equivalence. Regulatory agencies like the FDA and EMA explicitly accept PopPK for this purpose.

Can PopPK prove equivalence for complex drug delivery systems?

Yes. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program is already evaluating PopPK for complex delivery systems like extended-release tablets, inhalers, and transdermal patches. These products often have variable absorption patterns that traditional Cmax/AUC comparisons can’t fully capture. PopPK can model the entire concentration-time profile across populations, showing whether the delivery system produces consistent exposure despite differences in patient physiology.

Robert Cardoso

January 29, 2026 AT 03:44Population pharmacokinetics isn't magic-it's math with a side of wishful thinking. The FDA's 78-page guide reads like a PhD thesis written by someone who hates sleep. And yet, we're supposed to trust that a model built from sparse, noisy, real-world samples can replace controlled trials? Give me a break. If you can't measure AUC and Cmax properly, you don't get to call it bioequivalence. You call it guesswork with a fancy name.

SRI GUNTORO

January 31, 2026 AT 00:15It's disgusting how we're outsourcing patient safety to algorithms. These models are trained on data collected from people who can't even afford to read the consent forms. And now we're approving generics based on this? What's next-AI prescribing drugs over TikTok?

Chris Urdilas

February 1, 2026 AT 12:16Look, I get the frustration with traditional bioequivalence studies. They're expensive, slow, and often irrelevant. But PopPK? It's like trying to judge a car's performance by watching one person drive it once on a rainy Tuesday. The data's messy, the models are black boxes, and half the time you don't even know what covariates were included. Still-I'll admit, it's better than nothing. Just don't call it science.

Katie Mccreary

February 2, 2026 AT 11:38They’re not replacing traditional studies. They’re replacing accountability.

Amber Daugs

February 2, 2026 AT 22:22If you think PopPK is the future, you're ignoring the fact that 65% of pharmacometricians can't even agree on what validation means. That's not innovation-that's chaos dressed up in LaTeX. And don't get me started on NONMEM. It's 1980s software running on Windows 95 emulators. We're building global drug policy on a program that predates smartphones.

Ambrose Curtis

February 3, 2026 AT 15:52People act like PopPK is some revolutionary breakthrough, but honestly? It's just statistics with more steps. You collect data from real people, throw it into a model, and hope it doesn't overfit. I've seen models where they included 12 covariates and the model still couldn't predict if the patient was male or female. But hey, if the FDA says it's good enough, I guess we're all just guinea pigs now.

Jess Bevis

February 5, 2026 AT 04:41India's healthcare system can't even reliably track prescriptions. How are we supposed to trust PopPK data from clinics with no electronic records? This isn't science-it's colonialism with a statistical twist.

Rose Palmer

February 6, 2026 AT 14:52While the methodological challenges of population pharmacokinetics are significant, the ethical imperative to expand access to safe, effective therapeutics for vulnerable populations cannot be overstated. A structured, transparent, and rigorously validated PopPK framework represents not merely a technical advancement, but a moral evolution in regulatory science.

Howard Esakov

February 6, 2026 AT 19:51NONMEM is the only reason this works. The fact that you need a PhD and a time machine to use it means only elite pharma giants can afford to play. Meanwhile, generic companies in Bangladesh are slapping labels on pills and calling it equivalent. PopPK? More like Pop-Scam.

Mindee Coulter

February 8, 2026 AT 18:33Real patients aren't lab rats. If we want drugs that actually work for people, we need real data. Stop pretending healthy 22-year-olds are the norm.

Rhiannon Bosse

February 9, 2026 AT 11:46Wait-so the same people who told us vaccines were dangerous because they used mRNA are now fine with AI models predicting drug levels from one blood draw? What’s next? A TikTok algorithm prescribing insulin? I smell a conspiracy. Someone’s selling NONMEM licenses to Big Pharma. And no, I won’t explain my sources.

Bryan Fracchia

February 10, 2026 AT 20:28It's beautiful, really. We're moving from one-size-fits-all medicine to something that actually sees the person. The math is hard. The data is messy. But if we can show that a drug works the same for a 78-year-old with kidney disease as it does for a 30-year-old athlete-then maybe, just maybe, we're finally treating humans instead of averages.

John Rose

February 12, 2026 AT 10:32PopPK doesn’t replace traditional bioequivalence-it elevates it. The goal isn’t to simplify science, but to honor its complexity. When we design trials with real-world variability in mind, we’re not cutting corners-we’re building bridges between the lab and the living world.