Steroid Diabetes Risk Calculator

Assess Your Risk

This tool estimates your risk of developing corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia based on your steroid dose, BMI, and diabetes status.

Risk Assessment Results

When you start taking corticosteroids like prednisone or dexamethasone for asthma, arthritis, or an autoimmune flare-up, your body doesn’t just fight inflammation-it starts fighting your blood sugar too. Corticosteroid-induced hyperglycemia isn’t just a side effect. It’s a metabolic shift that can turn a healthy person into someone with dangerously high glucose levels in days. And if you already have diabetes, it can send your numbers into a tailspin. This isn’t rare. About half of hospitalized patients on high-dose steroids develop blood sugar spikes. Many don’t even know it’s happening until they’re admitted for something else.

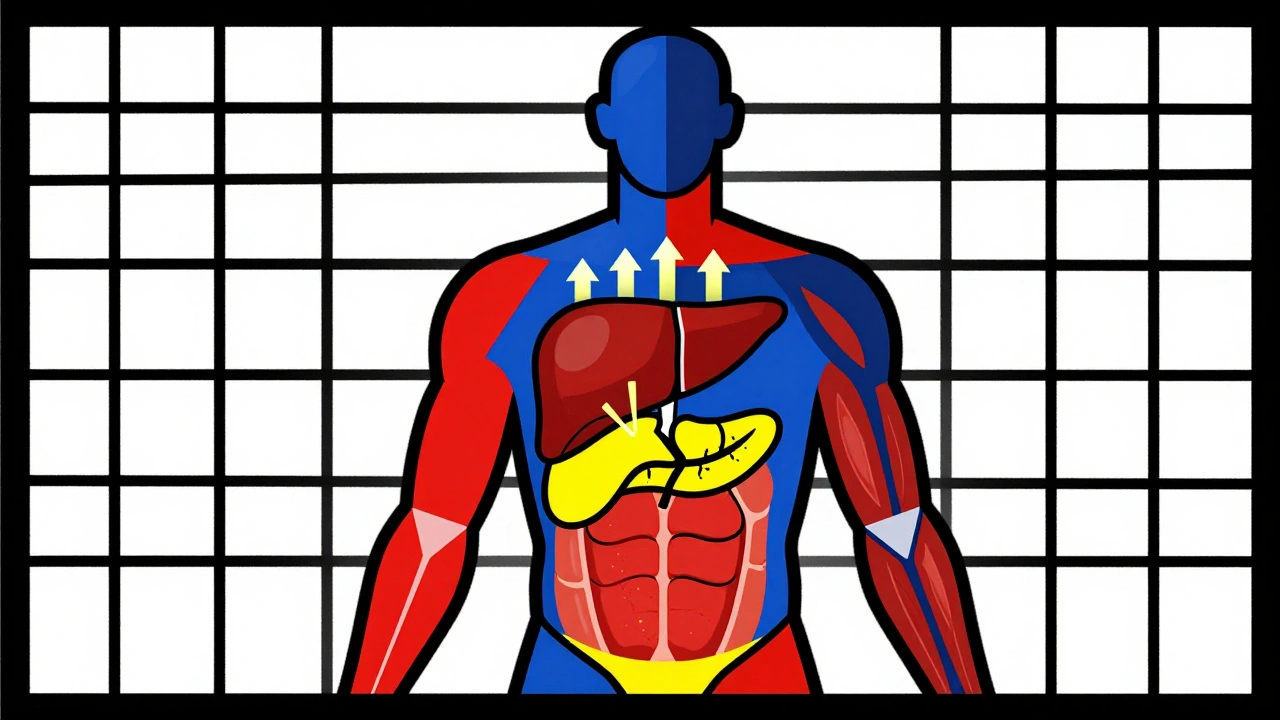

Why Steroids Make Your Blood Sugar Spike

Steroids don’t just cause sugar to rise-they rewire how your body handles it. In your liver, they crank up glucose production by nearly 38%. That means your liver starts pumping out sugar even when you haven’t eaten. At the same time, your muscles stop taking in glucose like they used to. Insulin can’t signal them properly because steroids break down the messaging system-insulin receptor substrate-1 and PI3K get suppressed by over 30%. Your fat cells start leaking free fatty acids, which makes insulin resistance worse. And your pancreas? It gets confused. Beta cells produce less insulin because the sensors that detect glucose (GLUT2 and glucokinase) stop working as well. Even a single 75 mg dose of prednisolone can shut down insulin secretion within two hours.

This isn’t type 2 diabetes. It’s not about long-term weight gain or poor diet. It’s a direct, dose-dependent chemical interference. The timing matters too. Most people get their steroid dose in the morning, so their blood sugar peaks between 8 a.m. and noon. By afternoon, it often drops back down. That’s why many patients test fine at their doctor’s office-because they checked after lunch. But their glucose was sky-high during the critical morning hours.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone on steroids develops high blood sugar. But some people are far more likely to. If you have a BMI over 30, your risk jumps 3.2 times compared to someone with a normal weight. If you already have prediabetes or impaired glucose tolerance, your risk shoots up nearly fivefold. Age plays a role too-people over 65 are more vulnerable. Even a family history of type 2 diabetes increases your chances, not because you inherited the disease, but because your body may already have a reduced ability to handle insulin stress.

It’s not just about your body. The steroid dose and type matter. A daily 20 mg dose of prednisone or its equivalent is the tipping point where monitoring becomes essential. Dexamethasone is more potent and longer-lasting than prednisone, so even lower doses can cause bigger spikes. Hydrocortisone, used for adrenal insufficiency, tends to be less disruptive-but it’s still a risk if taken long-term.

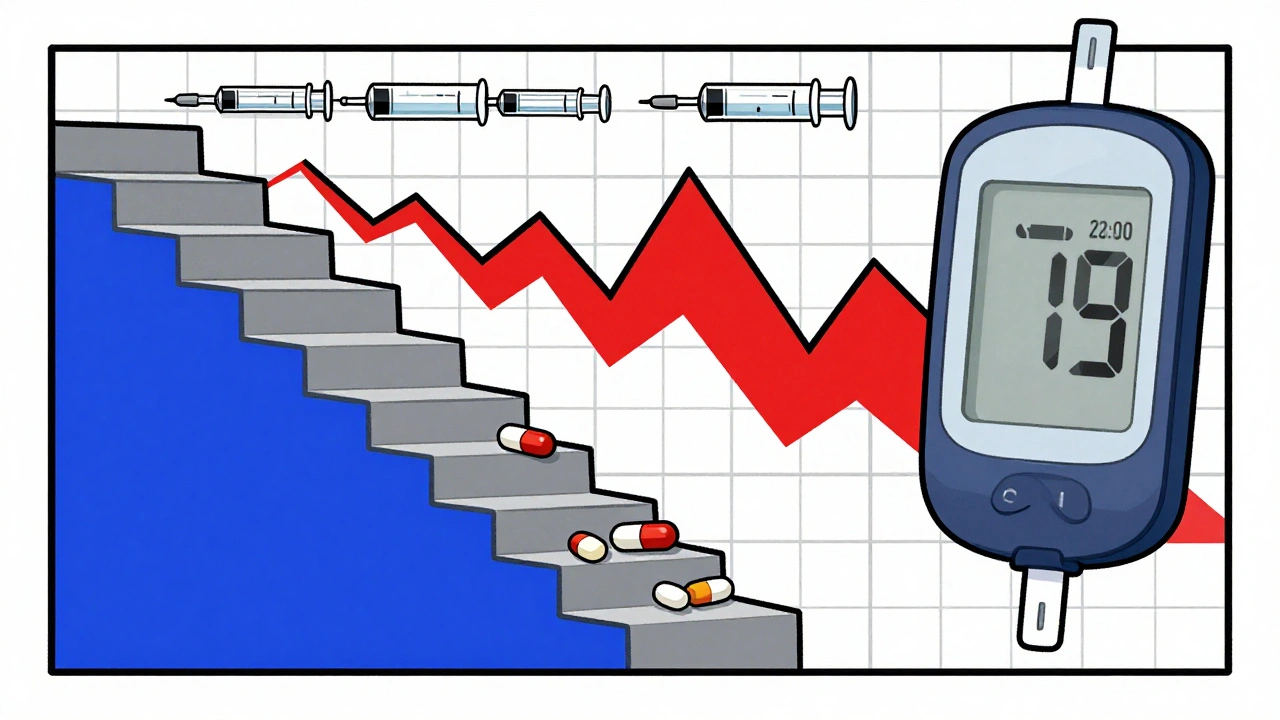

How to Monitor Correctly

Waiting for symptoms like thirst or fatigue to show up is too late. By then, you’re already at risk for hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state-a life-threatening condition that affects nearly 5% of severe cases. The standard advice? Start checking your blood sugar within 24 hours of your first steroid dose.

For high-risk patients, check fasting glucose and 2-hour post-meal glucose at least twice a day. Don’t just test in the morning. Test after lunch and dinner too. Why? Because insulin resistance lasts 16 to 24 hours after each dose. Even if you take steroids every other day, your glucose can still spike on off-days. One study found that continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) caught 68% more high glucose episodes than fingersticks alone. Many of these spikes happened overnight-when no one was checking.

CGMs are becoming the gold standard, especially during steroid tapering. As the dose goes down, your body tries to rebound. But insulin resistance doesn’t vanish overnight. That’s when people get hit with sudden hypoglycemia. Nearly 23% of patients on tapering steroids experience low blood sugar episodes, often without warning. If you’re on a CGM, you’ll see the drop coming. If you’re not, you might pass out before anyone realizes something’s wrong.

What to Do When Blood Sugar Rises

If your glucose is consistently above 180 mg/dL on two separate readings, it’s time to act. For patients without prior diabetes, the best approach is a basal-bolus insulin regimen-not sliding scale. Sliding scale means you give insulin only when blood sugar is high. That’s reactive. Basal-bolus is proactive. You give a long-acting insulin once or twice a day to cover background needs, and fast-acting insulin before meals to handle the spikes. Studies show this method improves glucose control by 35% compared to sliding scale alone.

If you already have type 2 diabetes, you’ll likely need to increase your insulin dose by 20% to 50%. Metformin alone won’t cut it. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists are often ineffective during active steroid use because the body’s insulin resistance is too severe. Insulin is the only tool that reliably brings glucose down in this situation.

Timing insulin to match steroid peaks is critical. If you take prednisone at 8 a.m., you’ll need the most insulin at breakfast and lunch. Your afternoon and evening insulin doses can be lower. Many hospitals use protocols that automatically adjust insulin based on steroid timing. In one Mayo Clinic program, insulin was triggered automatically when two consecutive readings hit 180 mg/dL. That program cut complications by over 50%.

What Happens When You Stop Steroids?

Stopping steroids doesn’t mean your blood sugar problems vanish. The insulin resistance fades slowly-over days to weeks. That’s why tapering is so dangerous. As the steroid leaves your system, your pancreas starts to recover, but your liver and muscles are still resistant. You might feel fine, but your insulin needs drop faster than you expect. That’s when hypoglycemia strikes. Patients report feeling dizzy, sweaty, or confused during tapering-often at night. This isn’t just inconvenient. It’s dangerous.

Some people never fully return to normal. About 19% to 32% of people who develop steroid-induced diabetes don’t go back to normal glucose levels after stopping steroids. For them, it becomes permanent type 2 diabetes. That’s why follow-up is non-negotiable. Three months after stopping, get an HbA1c test. If it’s above 6.5%, you have diabetes. If it’s between 5.7% and 6.4%, you have prediabetes. Either way, you need lifestyle changes-and possibly medication-to prevent progression.

Why Most Hospitals Get It Wrong

Despite clear guidelines from the American Diabetes Association and the Endocrine Society, only 58% of non-critical care units have formal protocols for steroid-induced hyperglycemia. That means most patients are managed on a case-by-case basis. Nurses might forget to check glucose. Doctors might assume it’s just “steroid side effects” and not treat it. One study found that patients in hospitals without protocols waited 42% longer to get treatment. That delay increases the risk of infection, longer hospital stays, and even death.

Even worse, many doctors don’t know the pattern. Only 44% of non-endocrinologists recognize that the glucose spike is highest in the morning. They treat it like regular diabetes-giving the same insulin dose all day. That leads to dangerous lows in the afternoon or overnight. Patients end up with more complications, not fewer.

What’s Coming Next

Researchers are working on smarter solutions. A trial called GLUCO-STER, funded by the NIH, is testing a machine learning tool that predicts your risk of steroid-induced hyperglycemia before you even start treatment. It looks at your BMI, HbA1c, steroid dose, and even your genes-specifically the GR-1B polymorphism. If the algorithm says you’re high risk, your care team can start monitoring and insulin right away, before your glucose spikes.

Long-term, the goal is to avoid steroids altogether. New drugs called tissue-selective glucocorticoid receptor modulators are in Phase II trials. These drugs are designed to reduce inflammation in joints or lungs without affecting the liver or pancreas. Early results show a 62% drop in hyperglycemia compared to standard steroids. If they work, they could change how we treat autoimmune diseases forever.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re prescribed corticosteroids, don’t wait. Ask your doctor: “Am I at risk for high blood sugar?” and “Should I start checking my glucose now?” Get a glucometer if you don’t have one. Know your target range-usually under 180 mg/dL before meals and under 200 mg/dL after meals. If you’re on insulin, learn how to adjust doses based on your steroid schedule. Keep a log of your readings, steroid doses, and meals. Bring it to every appointment.

If you’re a caregiver or family member, learn the signs of high and low blood sugar. Dizziness, confusion, extreme thirst, frequent urination, or sudden fatigue could mean something serious. Don’t assume it’s just the illness or the medication making you tired. It might be your blood sugar.

Steroids save lives. But they can also trigger hidden dangers. Monitoring isn’t optional. It’s part of the treatment. The more you know, the safer you’ll be.

Can corticosteroids cause permanent diabetes?

Yes, in about 19% to 32% of people who develop high blood sugar from steroids, the condition doesn’t reverse after stopping the medication. This is especially true for those with pre-existing insulin resistance, obesity, or a family history of type 2 diabetes. A follow-up HbA1c test three months after stopping steroids is essential to determine if diabetes has become permanent.

Is insulin the only treatment for steroid-induced hyperglycemia?

For moderate to severe cases, insulin is the most reliable and effective treatment. Oral medications like metformin, SGLT2 inhibitors, or GLP-1 agonists often don’t work well because the insulin resistance is too strong. In mild cases with no prior diabetes, diet and exercise may help-but only if the steroid dose is low and short-term. For doses over 20 mg prednisone daily, insulin is usually necessary.

Why does my blood sugar drop when I taper off steroids?

As steroid levels decrease, your body’s insulin resistance fades-but your pancreas may still be producing more insulin than needed. This mismatch can cause low blood sugar, especially at night. Many patients don’t realize their insulin dose needs to be lowered during tapering. Continuous glucose monitors are the best way to catch these drops early.

Should I check my blood sugar on days I don’t take steroids?

Yes. Steroid-induced insulin resistance can last 16 to 24 hours after a dose. If you take steroids every other day, your glucose can still be high on your “off” days. Monitoring on both days helps you see the full pattern and adjust treatment properly.

What’s the difference between steroid-induced diabetes and type 2 diabetes?

Steroid-induced diabetes is caused by direct interference with insulin signaling and glucose production-usually temporary and dose-dependent. Type 2 diabetes is a chronic condition driven by long-term insulin resistance and beta cell decline. Steroid-induced diabetes often shows morning-only spikes, while type 2 diabetes causes all-day high glucose. Treatment also differs: insulin is often needed for steroid-induced cases, while type 2 may respond to oral meds and lifestyle changes.

ATUL BHARDWAJ

December 3, 2025 AT 18:49My uncle on prednisone for rheumatoid arthritis never checked his sugar. Ended up in the ER with ketoacidosis. No one told him it could happen. Simple test couldve saved him.

Steve World Shopping

December 4, 2025 AT 00:20The pathophysiology is unequivocally rooted in glucocorticoid-mediated suppression of IRS-1/PI3K signaling cascades and GLUT2 downregulation in pancreatic beta cells. The hepatic gluconeogenic surge exceeds compensatory insulin secretion capacity, inducing a state of acute insulin resistance that mimics but is mechanistically distinct from T2DM. Standard glycemic algorithms are inadequate without circadian dosing correlation.

Lynn Steiner

December 5, 2025 AT 21:23I HATE when doctors act like this is normal 😭 My mom got 40mg of prednisone and they just said 'oh its just steroids'... she almost died from a DKA. Why dont they just warn people?? I'm so mad right now.

मनोज कुमार

December 7, 2025 AT 03:44Basal bolus insulin is the only way to go. Sliding scale is for lazy docs. Steroid spikes are predictable so treat them like a schedule not an emergency. Also CGMs are not luxury they are mandatory for anyone on >20mg prednisone daily. Stop being cheap with patient safety.

Joel Deang

December 7, 2025 AT 18:29wait so if i take steroids for my allergies i need to check my sugar?? i thought that was just for diabetics 😅 i got a glucometer from walmart but i dont even know how to use it lmao

Roger Leiton

December 8, 2025 AT 03:33This is so important!! I just started prednisone for my lupus flare and I didn't know any of this. I'm gonna start checking my sugar twice a day now 🙏 I even got a CGM and I'm so glad I did - caught a spike at 3am last night!!

Zed theMartian

December 8, 2025 AT 08:03Oh wow, so we're supposed to believe that a 75mg dose of prednisolone can 'shut down insulin secretion' like it's some kind of magic wand? This reads like a pharmaceutical white paper disguised as medical advice. Who funded this? Big Insulin? 😏

Ella van Rij

December 9, 2025 AT 15:30Wow. Just… wow. So I’m supposed to buy a CGM because some dude wrote a 2000-word essay on steroids? I’m pretty sure my doctor would’ve mentioned if I was at risk for ‘metabolic sabotage’… unless she’s just too busy doing her nails.

Rebecca M.

December 10, 2025 AT 07:39My aunt got on steroids for MS and then she started crying all the time and saying she felt like her body was betraying her… I didn’t realize it was the sugar. Now she’s on insulin and she says she feels like a robot. I miss her.

Shannara Jenkins

December 10, 2025 AT 22:36Hey everyone - if you're on steroids and you're scared, you're not alone. I’ve been through this twice. The key is to get a logbook (paper or app) and track your meals, doses, and numbers. Talk to your pharmacist - they’re awesome at helping you adjust. You got this 💪

Elizabeth Grace

December 12, 2025 AT 21:56I started monitoring after my doc said 'it's probably nothing' - turns out I was at 280 mg/dL at 7am and she didn't even check until noon. Now I have a CGM and I'm not scared anymore. It's just… a new normal. We can do this.