For years, if you wanted to know if a medication was safe during pregnancy, you looked for a letter: A, B, C, D, or X. It seemed simple. But that system was misleading. It made people think Category C meant ‘kind of risky’ and Category B meant ‘mostly safe,’ when in reality, those letters told you almost nothing about actual risks or benefits. That’s why, in 2015, the FDA replaced the letter system with something far more useful: the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR). Now, instead of a single letter, you get real, detailed information - if you know how to read it.

What Changed with the FDA’s New Labeling System?

The old pregnancy letter categories were created in 1979 and hadn’t kept up with modern science. Category A meant human studies showed no risk - but only about 2% of drugs had that label. Category C? That was the default for 70% of medications, meaning there was evidence of risk in animals, but not enough data in humans. Many doctors and patients assumed Category C meant ‘avoid at all costs,’ when it often just meant ‘we don’t have good data yet.’

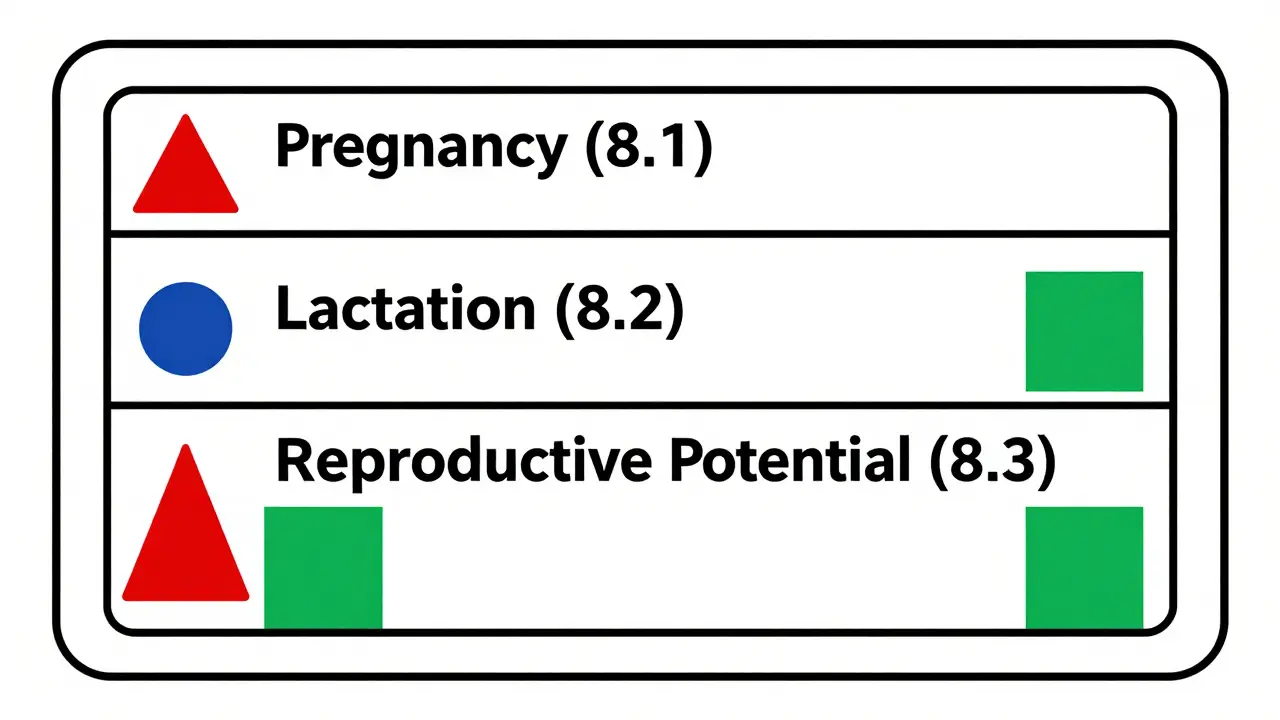

The PLLR fixed that. It removed the letters entirely and replaced them with three clear subsections in every drug’s prescribing information: Pregnancy (8.1), Lactation (8.2), and Females and Males of Reproductive Potential (8.3). Each section follows the same structure: Risk Summary, Clinical Considerations, and Data. This isn’t just a format change - it’s a shift in how we think about drug safety.

How to Read the Pregnancy Section (8.1)

The Pregnancy subsection starts with the Risk Summary. This isn’t vague. It tells you the background risk of birth defects (about 3% in every pregnancy) and miscarriage (10-20% of known pregnancies). Then it says how the drug changes that risk. For example: ‘Exposure during the first trimester is associated with a 1.5-fold increased risk of neural tube defects compared to the background rate.’ That’s meaningful. It doesn’t say ‘avoid.’ It says ‘here’s what the data shows.’

The Clinical Considerations section gives you action steps. It might say: ‘Monitor fetal growth every 4 weeks if the drug is used after 20 weeks.’ Or: ‘Consider switching to a safer alternative in the first trimester.’ This part is written for prescribers - but if you’re pregnant and reading your medication’s label, this is where you find out what your doctor should be watching for.

The Data section is the evidence behind the claims. It lists the studies: how many women were included, whether they were part of a registry, what trimester they were exposed in, and if the data came from animal studies, case reports, or large human trials. You’ll see things like ‘prospective cohort of 1,200 pregnancies’ or ‘no increase in malformations in 87 exposed infants.’ It’s not just a summary - it’s a window into the science.

One big improvement? Pregnancy exposure registries are now required. These are real-world tracking systems where women who take certain drugs during pregnancy voluntarily report outcomes. As of 2023, there are 47 active registries for drugs like antiseizure meds, antidepressants, and biologics. That means the data getting into these labels is growing - and getting better.

How to Read the Lactation Section (8.2)

If you’re breastfeeding, the Lactation section is just as important. The old system didn’t even have a separate section for this. Now, you get specific numbers. It tells you how much of the drug gets into breast milk - usually as a percentage of the mother’s dose. For example: ‘Infant exposure is less than 10% of the maternal dose.’ That’s far more helpful than saying ‘use with caution.’

It also tells you about potential effects on the baby. Is there a risk of drowsiness? Poor feeding? Changes in heart rate? It might say: ‘No adverse effects reported in 30 breastfed infants over 6 months of follow-up.’ Or: ‘Case reports suggest possible sedation in neonates; monitor for excessive sleepiness.’

Some labels even include pharmacokinetic data - like how long the drug stays in milk, or when the lowest levels occur (often 2-4 hours after the mother takes the dose). This helps you time feedings to reduce exposure. If you’re worried, you can ask your doctor: ‘Can I breastfeed 3 hours after taking this pill?’ The answer might be right there in the label.

What About Fertility and Contraception? (8.3)

This section is often overlooked, but it matters if you’re trying to get pregnant - or trying not to. It tells you whether the drug affects fertility in men or women. It says whether pregnancy testing is needed before starting treatment, and how often. And it lists what kind of birth control is recommended, including failure rates.

For example: ‘Effective contraception is required during treatment and for 30 days after the last dose. Use of a hormonal method with a failure rate of less than 1% per year is recommended.’ That’s clear. No guesswork. If a drug can cause birth defects, and you’re sexually active, this section tells you exactly what you need to do.

Why the Old System Was Misleading

Let’s say you saw a drug labeled Category C. You might think, ‘This is dangerous.’ But Category C could mean one of two things: either there’s clear risk in animals but no human data - or there’s weak human data showing no risk. The letter didn’t tell you which. That’s why 68% of people misinterpreted the old system, according to FDA research.

Now, with the PLLR, you see: ‘Animal studies showed increased risk of fetal malformations. No adequate human studies. However, 120 exposed pregnancies in clinical practice showed no increase in birth defects.’ That’s real context. You’re not guessing. You’re seeing the full picture.

What’s Still Hard About the New System?

It’s not perfect. The new labels are longer - often 300 to 500 extra words per drug. That’s a lot to read. A 2018 study found 62% of obstetricians felt overwhelmed at first. Family doctors, who see pregnant patients less often, reported feeling less confident. Many now turn to external resources like MotherToBaby or TERIS to help interpret the labels.

Another issue? Not all labels are equally detailed. Some are thorough. Others are still light on data, especially for older drugs. And while the FDA has pushed for updates, not every drug has been fully rewritten yet. As of 2023, about 78% of prescription drugs in the U.S. use the new format. The rest are still in transition.

There’s also confusion around risk numbers. A ‘2-fold increased risk’ sounds scary - until you realize the background risk was 1%. So now it’s 2%. That’s a small absolute change. The label should explain this, but sometimes it doesn’t. That’s why it’s important to ask your provider: ‘What’s the actual chance this will hurt my baby?’

How to Use This Information

You don’t need to be a doctor to read these labels. Here’s how to do it:

- Find the label. Go to Drugs.com, DailyMed, or the FDA’s website. Search for the drug name and click on ‘Prescribing Information.’

- Go to Section 8. Look for 8.1 (Pregnancy), 8.2 (Lactation), and 8.3 (Reproductive Potential).

- Read the Risk Summary first. What’s the background risk? What does the drug change? Look for numbers - not just words like ‘possible’ or ‘may.’

- Check Clinical Considerations. What should you or your provider monitor? Are there timing recommendations?

- Ask about the Data. If you’re unsure, ask your doctor: ‘Where did this info come from?’ A good provider will be able to explain the studies.

Don’t rely on apps or websites that still use the old letter system. They’re outdated. Always go to the official label.

What Resources Can Help You?

Even with the new labels, it’s okay to need help. Here are trusted tools:

- MotherToBaby - A free service run by the Organization of Teratology Information Specialists. Call or chat online with experts who explain drug risks in plain language.

- TERIS - A database used by clinicians that pulls data from pregnancy registries and peer-reviewed studies.

- FDA’s PLLR Navigator App - A free mobile tool that lets you search drug labels and highlights key information.

- Your pharmacist - Many now offer free 5-7 minute consultations on pregnancy and breastfeeding safety. Ask for one.

These aren’t just backup tools - they’re part of how the system works now. The PLLR didn’t remove the need for expert advice. It just made the advice better.

What’s Coming Next?

The FDA is working on making labels even clearer. In 2023, they proposed adding visual risk icons - like a small symbol for ‘high risk’ or ‘low risk’ - to help speed up reading. They’re also pushing for more data from underrepresented groups. Right now, only 15% of pregnancy registry participants are Black or Hispanic, even though they make up 30% of U.S. pregnancies. That’s a gap that needs fixing.

By 2025, the FDA plans to update 100% of pregnancy-related drug labels. And more drugs will be required to include lactation pharmacokinetic data - meaning we’ll know exactly how much gets into breast milk, not just estimates.

The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to give you real information so you can make the best choice for your health - and your baby’s.

Are the old pregnancy letter categories still valid?

No. The FDA removed the A, B, C, D, and X categories in 2015 under the Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling Rule (PLLR). Any drug label still showing these letters is outdated. The new system uses narrative descriptions with data-backed risk summaries, clinical guidance, and study details. Always check the official prescribing information on DailyMed or the FDA website for current labeling.

Can I trust drug labels if I’m breastfeeding?

Yes - but only if you’re reading the updated labels. The Lactation section (8.2) now provides specific data on how much of the drug passes into breast milk, usually as a percentage of the mother’s dose. For example, ‘infant exposure is less than 5% of maternal dose’ is much more useful than ‘use with caution.’ Look for information on potential infant effects, like drowsiness or feeding issues. If the label doesn’t mention breastfeeding, consult MotherToBaby or your pharmacist for the latest evidence.

What if my drug’s label says ‘risk cannot be ruled out’?

That phrase is gone from new labels. Instead, you’ll see actual numbers: ‘Increased risk of X by 1.5-fold compared to background rate’ or ‘No adverse effects reported in 120 exposed infants.’ If you’re reading an old label with vague language, it’s outdated. Ask your provider for the current prescribing information. The new format avoids vague terms and gives you measurable risk data.

Do I need to stop my medication if I’m pregnant?

Not necessarily. The new labels help you weigh risks versus benefits. For example, uncontrolled epilepsy or depression during pregnancy can be more dangerous than the medication. The Clinical Considerations section often says whether switching is recommended, or if continuing is safer. Never stop a medication without talking to your provider. The goal is to keep you healthy - because your health directly affects your baby’s.

How do I know if a pregnancy registry exists for my drug?

The Pregnancy section (8.1) of the drug label will list any active pregnancy exposure registry if one exists. It will include contact information and instructions for enrollment. As of 2023, 47 registries are tracking medications like antiseizure drugs, antidepressants, and biologics. If your drug doesn’t have a registry listed, it doesn’t mean it’s unsafe - just that data collection isn’t formalized yet. You can still report exposure through MotherToBaby.

Are generic drugs labeled the same as brand-name drugs?

Yes. By FDA regulation, generic drugs must have the same prescribing information as their brand-name counterparts, including the updated PLLR sections. If the brand-name version has a detailed Pregnancy and Lactation section, the generic must too. However, some older generics may still have outdated labels if the manufacturer hasn’t updated them. Always check the official label on DailyMed or the FDA site to confirm.

Ryan van Leent

December 18, 2025 AT 18:50Adrienne Dagg

December 19, 2025 AT 11:39Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 21, 2025 AT 10:13Sajith Shams

December 22, 2025 AT 22:22jessica .

December 23, 2025 AT 13:12Dev Sawner

December 24, 2025 AT 04:57shivam seo

December 25, 2025 AT 05:59Glen Arreglo

December 27, 2025 AT 02:26Moses Odumbe

December 27, 2025 AT 02:27