When you pick up a prescription, you might not notice the small, bold box at the top of the medication guide. But that box - the boxed warning - is one of the most important safety tools the FDA has. It’s not just a caution. It’s a red flag that says: this drug can kill you if used wrong. And over the last 40 years, these warnings have changed dramatically. They’re no longer vague. They’re specific. They’re data-driven. And if you’re a patient or a provider, not understanding how they evolve means you’re missing critical safety information.

What Exactly Is a Boxed Warning?

A boxed warning, also called a black box warning, is the strongest safety alert the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) can require on a prescription drug label. It appears in a thick, bordered box near the beginning of the prescribing information. The border used to be black, so people call it a "black box" - but today, the FDA allows other colors for digital formats. The content, however, hasn’t changed: it must describe serious, life-threatening risks. These include risks of death, hospitalization, permanent disability, or severe organ damage. These aren’t general side effects like nausea or dizziness. They’re events like sudden heart failure, suicidal behavior in young adults, liver failure, or a rare but deadly drop in white blood cells. The FDA only puts a boxed warning in place after strong evidence shows the risk is real, significant, and preventable with proper use. Since 1979, when the FDA first introduced boxed warnings, they’ve become a core part of drug safety. By 2025, about one-third of all major safety actions taken by the FDA involve boxed warnings. For drugs approved between 2001 and 2010, over 32% carried one. And today, nearly 4 in 10 drugs on the market have at least one.Why Do Boxed Warnings Change?

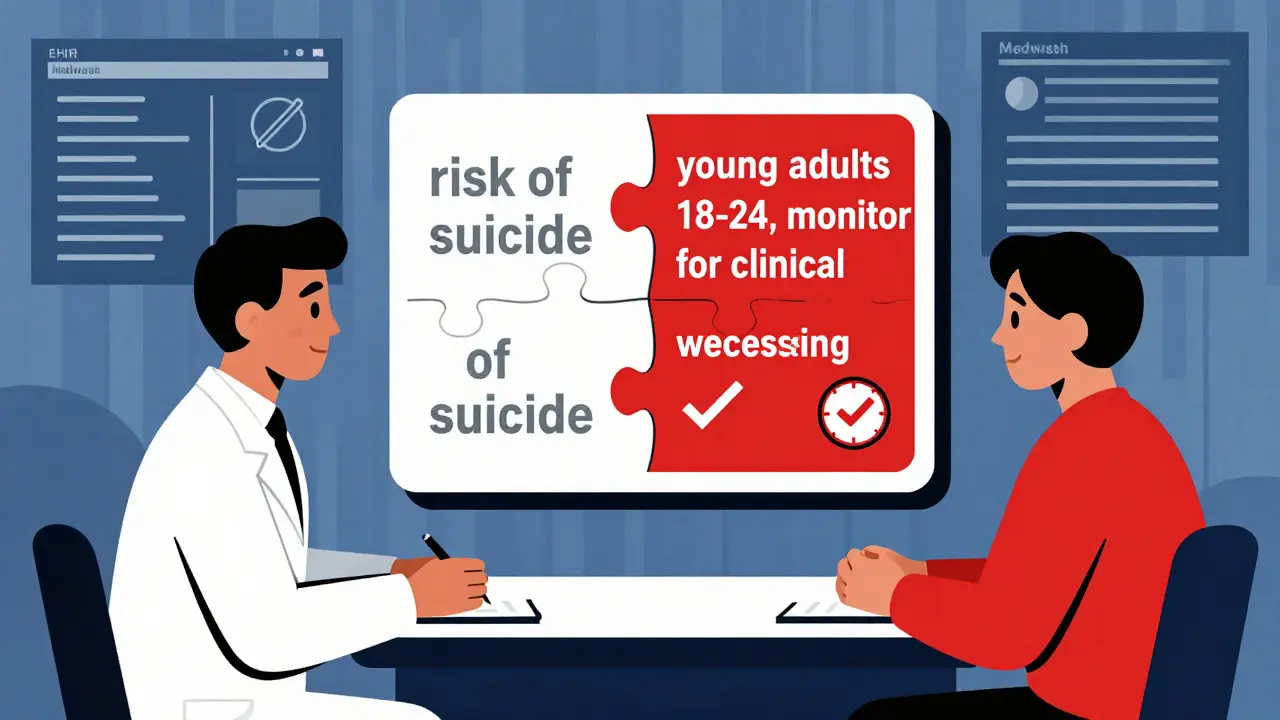

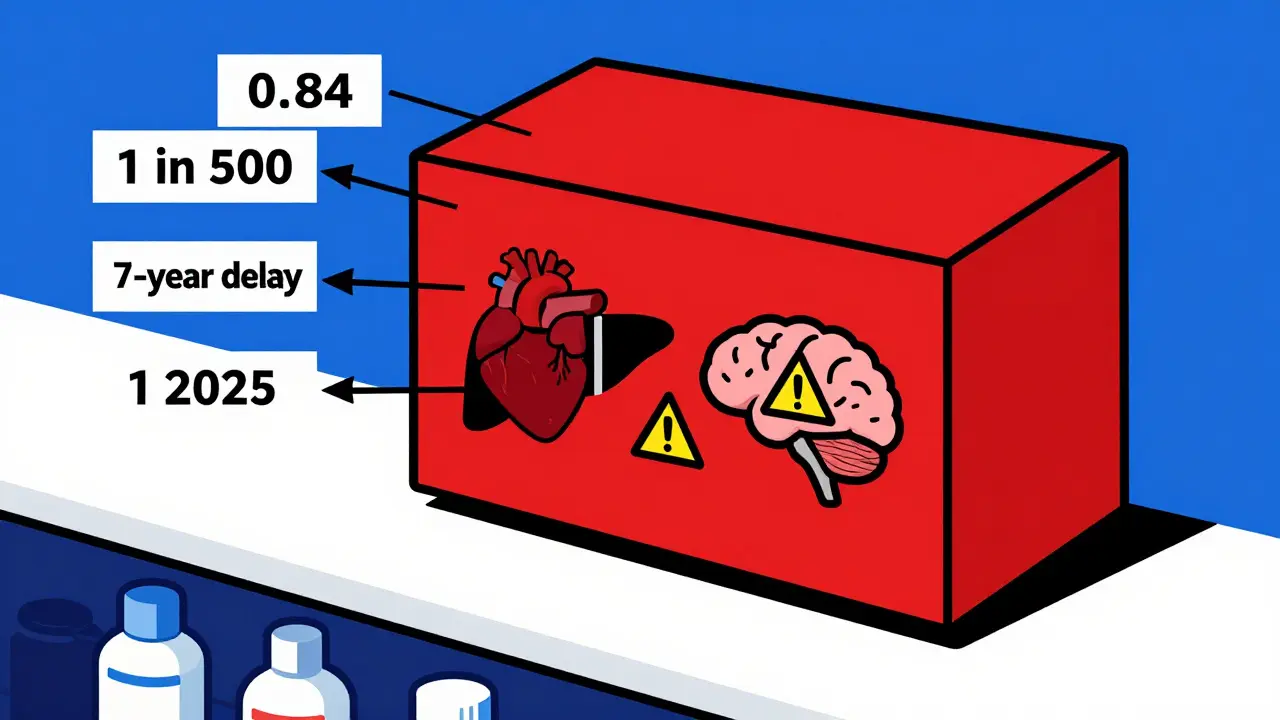

Boxed warnings don’t stay the same. They change because medicine changes. New data comes in. Real-world use reveals risks that didn’t show up in clinical trials. Sometimes, a warning is added. Sometimes, it’s removed. Sometimes, it’s rewritten to be clearer. Take Chantix (varenicline), a smoking cessation drug. In 2009, the FDA added a boxed warning about depression and suicidal thoughts. Doctors were alarmed. Patients stopped taking it. But in 2016, a massive study of over 8,000 people found no real difference in psychiatric events between those on Chantix and those on placebo. The FDA removed the warning. That’s not a flip-flop - it’s science catching up. Or look at Clozaril (clozapine), used for treatment-resistant schizophrenia. In 2025, its boxed warning was updated to include a specific number: 0.84 cases of myocarditis per 1,000 patient-years. That’s a 7-fold increase compared to other antipsychotics. Before, the warning just said "risk of heart inflammation." Now, it tells you exactly how often it happens - and that you must check heart function in the first 4 weeks of treatment. These aren’t random updates. They’re responses to real-world data from millions of patients, reported through the FDA’s MedWatch system. In 2024 alone, over 1.2 million adverse event reports came in. Some led to new warnings. Others led to changes in existing ones.How Boxed Warnings Have Gotten More Specific

Early boxed warnings were broad. In the 1980s and 90s, you’d see things like "risk of serious liver damage" or "may cause suicidal behavior." No numbers. No specific groups. No clear actions. Today’s warnings are surgical. They name exact populations, define severity levels, and tell you what to do. For example, antidepressant warnings changed dramatically between 2004 and 2006. The first version said only that children and teens had an increased risk of suicidal thoughts. By 2006, it expanded to include young adults aged 18 to 24. It also added: "Monitor patients for clinical worsening, suicidality, and unusual changes in behavior." That’s not just a warning - it’s a clinical instruction. Unituxin (dinutuximab), a cancer drug for neuroblastoma, had its warning updated in 2017. It replaced "neuropathy" with "neurotoxicity" - a more precise term that reflects how the drug damages nerves. It also added exact stopping criteria: "Discontinue if patient develops severe unresponsive pain, severe sensory neuropathy, or moderate to severe peripheral motor neuropathy." That’s not vague. It’s actionable. This shift matters. A 2021 study found that warnings with specific numbers and clear actions had a 78% compliance rate among prescribers. Vague warnings? Only 42% compliance.

How Long Does It Take for a Warning to Appear?

There’s a delay. A big one. For drugs approved in the 1990s, the average time from approval to boxed warning was about 7 years. Today, it’s closer to 11 years. Why? One reason: drugs are approved faster. The Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) of 1992 sped up approvals. That meant more drugs reached patients before long-term risks were known. The FDA now relies heavily on post-market surveillance - tracking what happens after approval. Another reason: modern drugs are more complex. Targeted cancer therapies, gene treatments, immunotherapies - these can have rare but devastating side effects that only show up after hundreds or thousands of patients use them. It takes time to see patterns. But that’s changing. The FDA’s 2023 Modernization Act 2.0 requires better use of real-world data from electronic health records. Pilot programs are testing systems that could flag safety signals in weeks, not years. By 2027, the goal is to cut the warning lag from 18-24 months down to under 6 months.Who Uses Boxed Warnings - and How?

Pharmacists use them every day. A 2023 survey of 854 hospital pharmacists found 89.7% consider boxed warnings essential. For drugs like pimozide (which can cause fatal heart rhythm problems) or clozapine (which can wipe out white blood cells), pharmacists won’t fill the script unless the patient meets strict monitoring requirements. But doctors? Not always. A 2017 study found only 43.6% of primary care physicians could correctly identify which drugs had boxed warnings during a patient visit. Family doctors were even less likely to know - 76% reported confusion. Why the gap? Boxed warnings are buried in dense prescribing documents. Many doctors don’t read them unless something goes wrong. And with over 200 drugs carrying warnings today, it’s easy to miss one. Patients often don’t see them at all. The warning is in the professional prescribing guide - not the patient leaflet. That’s a problem. If you’re on a drug with a boxed warning, you need to know what to watch for. Ask your doctor: "Is there a boxed warning for this? What does it mean for me?"

How to Track Changes Yourself

You don’t have to wait for your doctor to tell you about a change. The FDA makes this information public. Start with the Drug Safety-related Labeling Changes (SrLC) database. It’s free, searchable, and updated every quarter. It includes all changes since January 2016. You can search by drug name, warning type, or date. For older changes (before 2016), use the MedWatch Medical Product Safety Information archive. It’s less user-friendly but still searchable. The Drugs@FDA database shows the full history of a drug’s approval and labeling changes. You can see exactly when each warning was added or modified. And if you want summaries, the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy publishes quarterly updates on labeling changes - including boxed warnings. The April-June 2025 issue covered 17 updates across 14 drugs.What to Do When a Warning Changes

If you’re a patient:- Don’t stop your medication without talking to your doctor.

- Ask: "Has anything changed in the warning for my drug?"

- Find out what signs to watch for - and what to do if you see them.

- Keep a list of all your medications and their warnings.

- Check the SrLC database quarterly - even if you think you know your drugs.

- Update your EHR alerts. Many systems can be configured to flag drugs with recent boxed warning changes.

- Use the new, specific language in your patient conversations. Don’t say "risk of liver damage." Say "this drug can cause liver failure in 1 in 500 patients, especially if you drink alcohol. We’ll check your liver enzymes every 2 weeks for the first 3 months."

The Future of Boxed Warnings

The system isn’t perfect. Too many warnings can lead to "warning fatigue" - where doctors start ignoring them. Industry analysts predict that by 2030, nearly half of all marketed drugs will carry a boxed warning. But the FDA is adapting. New pilot programs are testing real-time warning updates based on EHR data. Imagine this: a patient on clozapine starts showing early signs of heart inflammation. Their EHR flags it. Within days, their doctor gets an alert: "Clozapine boxed warning updated - cardiac monitoring required. Patient meets criteria." That’s the future. More precise. Faster. Integrated into care. Right now, boxed warnings are the best tool we have to prevent drug-related deaths. But they’re only as good as the people who read them - and the data behind them. Understanding how they evolve isn’t just academic. It’s life-saving.Are boxed warnings the same as contraindications?

No. A contraindication means the drug should not be used at all in certain situations - for example, if you have a known allergy or severe liver disease. A boxed warning means the drug can still be used, but only with extreme caution, monitoring, or restrictions. It’s a risk that can be managed, not a hard stop.

Can a boxed warning be removed?

Yes. If new evidence shows the risk is not as serious as once thought, or if the benefit clearly outweighs the risk in real-world use, the FDA can remove it. Chantix’s 2016 removal is the clearest example. The warning was based on early data that didn’t hold up under larger, longer studies.

Do boxed warnings apply to over-the-counter drugs?

No. Boxed warnings are only required for prescription drugs. Over-the-counter medications have different labeling rules and don’t use the boxed format. That doesn’t mean they’re safe - but the FDA reserves the strongest alerts for drugs that require a doctor’s oversight.

Why do some drugs have multiple boxed warnings?

Because they carry multiple serious risks. For example, clozapine has warnings for agranulocytosis (dangerously low white blood cells), myocarditis (heart inflammation), seizures, and aspiration pneumonia. Each one is life-threatening on its own. The FDA adds each warning as evidence accumulates - even if they’re unrelated.

How often are boxed warnings updated?

There’s no fixed schedule. Updates happen whenever new safety data emerges. In 2025, the FDA issued 17 boxed warning updates in just one quarter. Some drugs get updated every few years. Others go a decade without change. The key is monitoring the FDA’s SrLC database quarterly - especially if you’re taking a drug that’s been on the market for more than 5 years.

jaspreet sandhu

January 2, 2026 AT 09:12People think these warnings are magic shields but they’re just paper tigers. I’ve seen doctors ignore them for years. The real danger isn’t the drug-it’s the system that lets lazy clinicians skip reading the fine print. If you’re not checking the SrLC database every quarter, you’re gambling with lives.

LIZETH DE PACHECO

January 3, 2026 AT 05:25This is one of the clearest explanations I’ve ever read. As a nurse, I’ve had patients panic when they see ‘boxed warning’ and assume the drug is banned. This helps me explain it’s not ‘don’t take it’-it’s ‘take it with eyes wide open.’ Thank you.

Liam George

January 4, 2026 AT 18:31Let’s be real-these warnings are corporate cover-ups. The FDA doesn’t remove warnings because science changed. They remove them because the pharma lobby paid off the regulators. Chantix? That was a PR stunt. They knew the data was flawed but needed sales to keep climbing. Wake up.

Kristen Russell

January 5, 2026 AT 07:50My dad was on clozapine. The warning saved his life. We caught the early signs of myocarditis because we knew what to look for. This isn’t bureaucracy-it’s a lifeline.

Lee M

January 5, 2026 AT 11:08There’s a reason why 40% of drugs have these now. We’re not being paranoid-we’re being honest. Modern medicine is powerful, but power without transparency is tyranny. These warnings are the only check we have on the machine.

sharad vyas

January 6, 2026 AT 21:44In India, we don’t even get these warnings properly. Pharmacists hand out pills like candy. I wish the FDA’s transparency could be exported. A simple QR code on the bottle linking to the latest warning would change everything.

Dusty Weeks

January 8, 2026 AT 19:56so like… if a drug gets a boxed warning… does that mean it’s basically a death sentence? 🤔 i mean i get it but also… why do they even sell it then? 🤷♂️

Olukayode Oguntulu

January 9, 2026 AT 18:26The entire framework is a performative spectacle. Boxed warnings are the pharmaceutical industry’s way of outsourcing moral responsibility to the patient while maintaining profit margins. The shift from vague to specific isn’t progress-it’s a rhetorical refinement designed to make negligence look like diligence. We’ve turned medical ethics into a compliance checklist. The FDA doesn’t protect you; it mediates between corporate liability and public trust. And yet, we treat these boxes like sacred scripture, when they’re just legal artifacts dressed up as wisdom.

Matthew Hekmatniaz

January 10, 2026 AT 13:31I’ve worked with refugee patients who don’t speak English and struggle to read at all. These warnings are useless to them unless we translate them into plain language and walk through them with interpreters. It’s not enough to publish them-we have to deliver them with dignity.

Bill Medley

January 12, 2026 AT 08:45The empirical data supporting the increased specificity of boxed warnings is compelling. The 78% compliance rate versus 42% for vague warnings is statistically significant and clinically meaningful. Further standardization of terminology across labeling systems would enhance interprofessional communication.

Bryan Anderson

January 13, 2026 AT 01:42I appreciate the depth here. As a pharmacist, I’ve seen how confusing it is when warnings change. I always print out the latest labeling changes and keep them in my reference binder. It’s a small habit, but it keeps me honest. Thank you for highlighting the SrLC database-it’s a hidden gem.

Sally Denham-Vaughan

January 14, 2026 AT 12:33my grandma’s on three drugs with boxed warnings. she doesn’t know any of this. i’m printing this out for her doctor. thank you.

Richard Thomas

January 16, 2026 AT 09:45There’s a deeper question here: if we’re relying on post-market surveillance to catch what clinical trials miss, are we just using patients as lab rats? We praise the system for being data-driven, but the data comes from suffering. Is that ethical? Or are we just numbing ourselves to the cost of innovation? The boxed warning isn’t a solution-it’s a confession that we don’t know enough until someone dies.

Alex Warden

January 17, 2026 AT 04:04Everyone is making this too complicated. If a drug has a boxed warning, you don’t take it unless you have no other choice. Simple. No numbers, no studies, no databases. If your life isn’t on the line, don’t risk it. The FDA doesn’t put those boxes there for fun. They put them there because people are dying. End of story.

Paul Ong

January 18, 2026 AT 00:01Just checked my meds-two have boxed warnings. I’m gonna call my doc tomorrow. This post saved me from a bad decision. Thanks for the clarity