When a critical medication expires, it’s not just a logistics issue-it’s a patient safety emergency. Imagine a patient in the ICU on a continuous infusion of fentanyl, and suddenly, the vials are marked "expired." No more supply. No more backup. What do you do? If you’re guessing or relying on memory, you’re risking harm. The right answer isn’t about who gets the last dose-it’s about having a clear, step-by-step plan in place before the crisis hits.

Why Expired Medications Are Different from Shortages

Expired medications and drug shortages feel similar: both leave you without the drug you need. But they’re not the same. A shortage means the manufacturer can’t produce enough. An expiration means the drug you already have is no longer safe to use. The FDA says medications lose potency over time, and in some cases, break down into harmful compounds. That’s why you can’t just use an old bottle because "it looks fine." Critical drugs-like sedatives for ventilated patients, vasopressors for shock, or neuromuscular blockers during surgery-have zero room for error. A wrong substitution can lead to prolonged sedation, cardiac arrest, or even death. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) estimates that 42% of all critical care drug shortages involve medications that also expire frequently. That overlap is where the real danger lies.

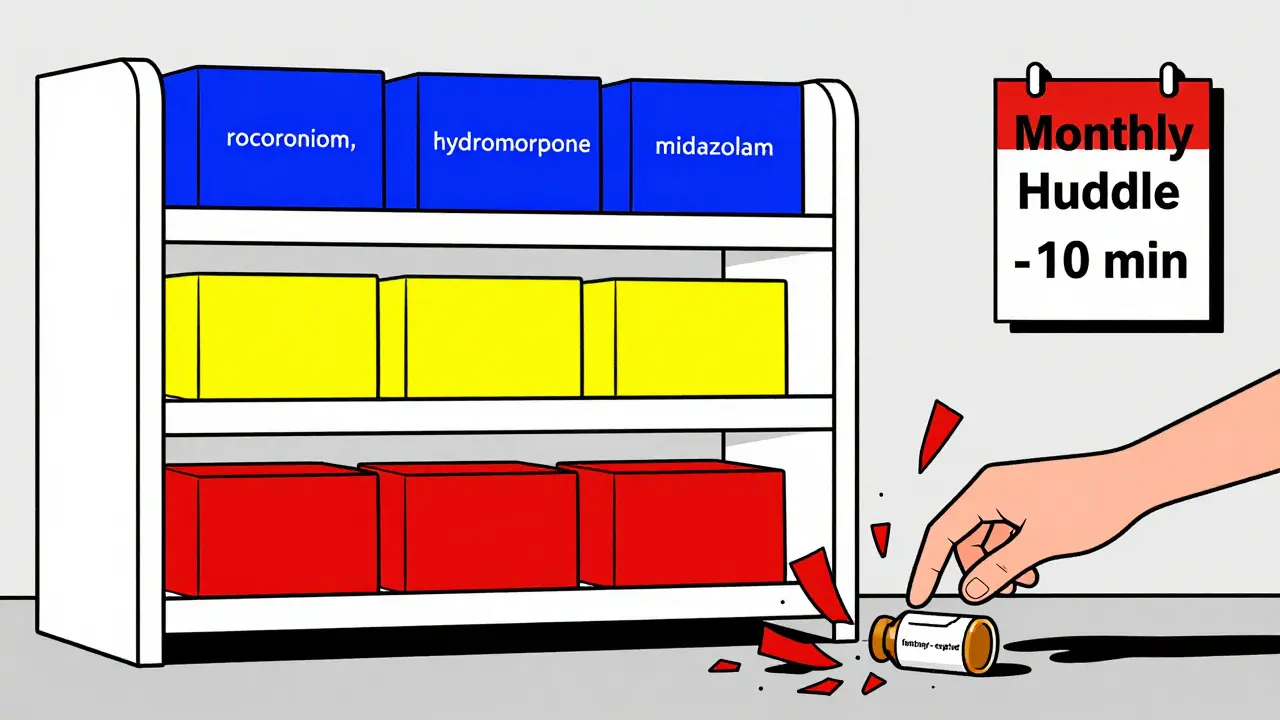

The Three-Tier Replacement System

Top hospitals don’t wing it. They use a tiered system developed by critical care pharmacists. This isn’t theoretical-it’s based on real-world outcomes from over 10,000 ICU cases. Here’s how it works:

- 1st line: The gold-standard alternative. Same mechanism of action, same dosing profile, same monitoring requirements. For example, if cisatracurium expires, rocuronium is the 1st-line replacement because it has nearly identical pharmacokinetics.

- 2nd line: A viable option, but with caveats. Maybe it requires more frequent monitoring, or has a different half-life. Vecuronium might be used if rocuronium isn’t available, but you’ll need to adjust infusion rates and check neuromuscular function more often.

- 3rd line: Last resort. Often older, less predictable, or with more side effects. Atracurium or pancuronium might be used only if nothing else is left-but they carry higher risks of prolonged paralysis or cardiovascular instability.

This system isn’t just a list. It’s a decision tree. Each tier comes with specific dose conversions, monitoring protocols, and warning signs. For instance, switching from fentanyl to hydromorphone isn’t a 1:1 swap. Hydromorphone is 5 to 7 times more potent. A patient on 100 mcg/hour of fentanyl might need only 15 mcg/hour of hydromorphone. Get it wrong, and you overdose-or trigger withdrawal.

Who Decides? The Role of the Pharmacist

You can’t delegate this to a nurse or a resident without training. Only pharmacists with critical care experience can reliably weigh these choices. Why? Because they understand pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and patient-specific factors like kidney function, liver disease, or age-related metabolism changes.

Research from CU Anschutz shows that hospitals with dedicated critical care pharmacists on rounds cut ICU mortality by 18.7% and reduced length of stay by 2.3 days. That’s not luck-it’s because pharmacists catch subtle mismatches. For example, a patient on renal replacement therapy might need a different sedative than one with normal kidney function. A pharmacist spots that. A nurse might not.

And it’s not optional anymore. The Journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy calls pharmacist-led medication management the standard of care in critical settings. If your hospital doesn’t have a pharmacist involved in these decisions, you’re operating outside accepted guidelines.

How to Build a Protocol (Step by Step)

Here’s what a working protocol looks like in practice. It’s not a document you file away. It’s a living system:

- Validate the expiration-Check the lot number, storage conditions, and manufacturer’s expiration date. Don’t assume. Some drugs, like insulin or epinephrine, degrade faster if exposed to heat.

- Assess remaining stock-How many doses are left? Is it enough to cover one shift? Two days? This tells you how urgent the replacement needs to be.

- Identify affected patients-Not all patients need the same drug. A trauma patient on neuromuscular blockers is different from a septic patient on vasopressors. Prioritize based on clinical urgency.

- Match to tiered alternatives-Use your pre-approved list. Don’t improvise. If your hospital doesn’t have one, build it now using ASHP guidelines.

- Adjust doses and monitor-Every substitution needs a new dosing plan. Use tools like Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale (RASS) for sedatives or mean arterial pressure (MAP) for vasopressors.

- Update the electronic record-If the order isn’t changed in the system, the next nurse won’t know what was given. Barcoding helps prevent errors.

- Document and review-After the transition, hold a 15-minute huddle. What worked? What didn’t? Update the protocol for next time.

Hospitals that do this consistently have less than 5% of medications expire. Those that don’t? Up to 18% of critical drugs go to waste annually. That’s not just money lost-it’s lives at risk.

What Happens Without a Protocol?

When there’s no plan, chaos follows. A 2024 survey found that 47% of hospitals used a "first come, first served" system during shortages. That means the patient who wakes up first gets the drug. The others? They wait. Or they get a less effective substitute. One ICU nurse told us: "We had three patients on norepinephrine. Only one had the replacement. The other two had dopamine. Two of them coded within 12 hours." Community hospitals are hit hardest. Only 42% have formal replacement protocols. Academic centers? 89%. That gap isn’t just about money-it’s about training, resources, and culture. Without a pharmacist, a nurse might reach for what’s on the shelf. That’s how you end up giving a muscle relaxant meant for surgery to a sedated patient. The result? A 11.2-day longer hospital stay per incident, according to one intensivist’s data.

Technology Can Help-But It’s Not Magic

Automated inventory systems with 30-day expiration alerts reduce waste by up to 68%. Barcode scanning prevents wrong-drug errors. AI tools are now being tested to recommend substitutions based on 147 patient variables. Early results show 94.7% agreement with expert pharmacists.

But tech doesn’t replace judgment. It supports it. An AI can say: "Try hydromorphone at 15 mcg/hour." But only a pharmacist knows whether the patient just came off opioids, has liver cirrhosis, or is on a drug that interacts with hydromorphone. That’s why the best systems combine alerts with pharmacist review.

What You Can Do Today

You don’t need a $1 million system to start. Here’s what works right now:

- Ask your pharmacy team: "Do we have a written protocol for expired critical drugs?" If not, push for one.

- Start with one high-risk drug-like fentanyl, norepinephrine, or midazolam. Build a tiered list for just that one.

- Hold a monthly 10-minute huddle with nurses, pharmacists, and ICU docs to review near-misses and near-expirations.

- Track how many expired drugs you have each month. If it’s more than 3%, you have a systemic problem.

The FDA is moving toward extending expiration dates based on real stability data-potentially cutting waste by 20%. But until then, the responsibility is yours. Every expired vial is a warning. Don’t wait for a crisis to act.

What’s the difference between an expired medication and a drug shortage?

An expired medication is one that has passed its manufacturer-set expiration date and is no longer guaranteed to be safe or effective. A drug shortage means the manufacturer can’t produce enough supply, but the existing stock may still be within its expiration window. Expired drugs must be discarded; short-supply drugs may still be used, but with rationing or substitution.

Can I use an expired medication if it looks fine?

No. Even if the liquid looks clear or the pill looks unchanged, chemical breakdown can occur without visible signs. Some drugs, like insulin or epinephrine, degrade into harmful compounds. The FDA and ASHP strictly advise against using any medication past its expiration date, especially in critical care.

Who should be responsible for choosing replacement drugs?

A critical care pharmacist. They’re trained in pharmacokinetics, drug interactions, and patient-specific factors like kidney or liver function. Nurses and doctors may assist, but without pharmacist input, substitutions carry high risk of dosing errors or adverse events.

Why do community hospitals struggle more with expired medications?

They often lack dedicated critical care pharmacists, automated inventory systems, and formal protocols. Only 42% of community hospitals have replacement guidelines, compared to 89% of academic centers. This leads to inconsistent, reactive decisions that increase patient risk.

What are the most common mistakes when replacing expired drugs?

The top three are: 1) Using a 1:1 dose conversion when the alternative has different potency (e.g., fentanyl to hydromorphone), 2) Failing to update electronic orders, leading to duplicate or missed doses, and 3) Not monitoring for withdrawal or adverse effects after the switch. These errors cause 32% of preventable ICU complications related to expired drugs.

Liam Crean

February 18, 2026 AT 11:11Man, I’ve seen this play out in my ICU. We had a fentanyl shortage last winter, and the pharmacy didn’t have the tiered protocol ready. They just handed out whatever was in stock. One patient went into withdrawal at 3 a.m. - shook so bad they pulled out their lines. We lost 12 hours of recovery time because no one had a cheat sheet. Now we have laminated cards taped to every med cart. Simple. Doesn’t need AI. Just common sense.